Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

The DU Lounge

Related: Culture Forums, Support ForumsThe Spirit of '70

https://www.affidavit.art/articles/spirit-of-70

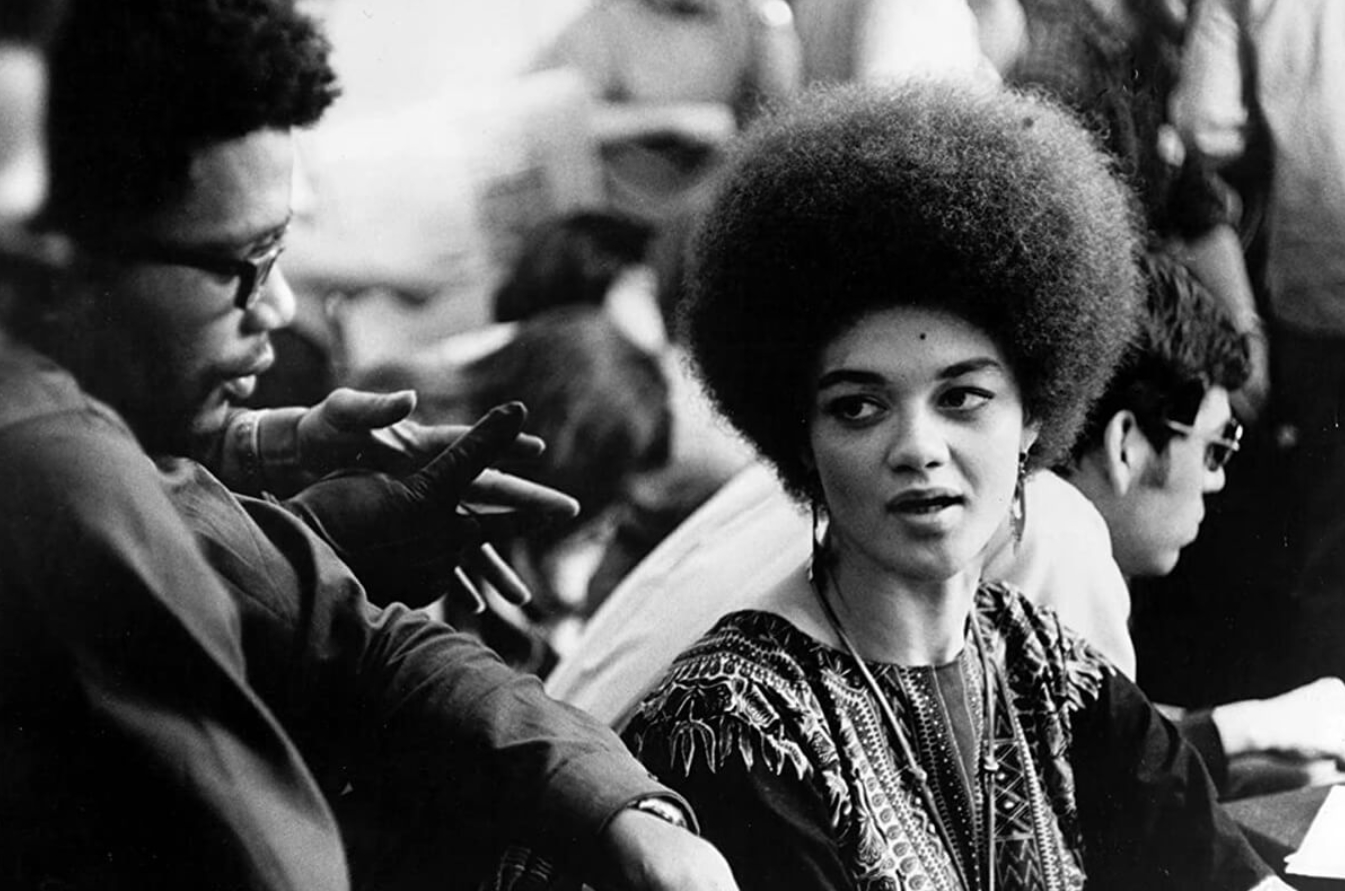

Kathleen Cleaver on the set of Zabriskie Point.

The amber waves of Zabriskie Point’s opening credits harden into its first scene; the psychedelic pumps and skitters of Pink Floyd’s “Heart Beat, Pig Meat” die down so the characters, college students contemplating a strike, can speak. Kathleen Cleaver of the Black Panther Party is there (playing a student, but also herself). So is activist Frank Bardacke. Discussion has turned to the list of demands. A blonde woman wants to abolish the ROTC. The Panther next to Cleaver lays it out: where have all these fearless white revolutionaries been for the last three hundred years? “Molotov cocktails is a mixture of kerosene and gasoline,” he says. “White radicals is a mixture of bullshit and jive.” There are scattered protestations from the white radicals in the room. Are you willing to die? asks one. A Black student retorts: Black people are dying. Mark, our pale, blue-eyed, shag-haired hero, stands up. He is prepared to die, too, he tells the assembly. But “not of boredom.” How to watch this film today, as the radicalism of the fabled 1960s walks the land once more? I began this essay during a pandemic. Since then, George Floyd’s murder by cop has compelled people to break quarantine and take to the streets, sometimes to confront the police. Molotov cocktails, indeed, have arced through the teargas, thrown by radicals of all races. It is the Movement rephrased for the present. But it is also, more importantly, something new. And in the context of this erupting urgency, Michelangelo Antonioni’s lush, confused film is all the more cautionary, a warning about the problematics of allyship and the seduction of myth. The students launch their strike. Antonioni works his own staged scenes (a standoff in the library, a stricken cop, a Black Panther gunned down) into newsreel of an actual campus uprising at San Francisco State in 1968.

A still from the author's film Walk Thru Walls.

Zabriskie Point is set amid the social strife of the late 1960s—it was released one month before the massacre at Kent State, two months after police murdered Fred Hampton while he slept—but is focused on the story of one disaffected white youth, a rebel without a cause and all that. The plot is violent in an ambient, aimless way. Thus, the film glosses over the great omission of the American myth, the fact that white supremacy has always walked hand in hand with freedom, progress, and the frontier. It was 1968. Antonioni was riding high on the success of his first English language film, 1966’s Blowup, a dark vision of swinging London, and America was next. America was important, thought the Italian auteur, because America was a future-facing, frontier country, and its youth the most futureward of all. An assistant to the director spotted Mark Frechette at a Boston bus stop shouting obscenities: “He’s 20,” she told her boss, “and he hates.” Antonioni cast him immediately. He found his starlet, Daria Halprin, dancing in a documentary on the counterculture. In Mark’s handsome, almost sociopathically wry face, in Daria’s flowering, innocent limbs, the auteur saw his metaphor: the Movement’s firebrands turning inward, to self-immolation. Mark and Daria were not actors. They were real, beautiful, white American youths. Daria was the daughter of a Bay Area choreographer, and Mark was a Boston native and itinerant handyman bidding to join Mel Lyman’s cult. Both use their real names in the film. Antonioni used (or tried to use) their real idealism. The director wanted rawness, authenticity, wildness—the West in the Continental mind—and he got it: a shallow-focus misapprehension of the Movement as only a 50-something European man could see it, through a lens as grandiose as it was bitter.

And so, Zabriskie Point is a gorgeous mess. The plot is dumb, the acting (who knew?) is wooden, the dialogue is a labored caricature of America structured by binaries like students/cops, free/trapped, and nature/civilization. The film valorizes free love as much as lost causes. Mark buys a gun, but it never goes off. Daria explodes a building with her mind. Contemporary film critics thought it was a joke. “I want to avoid all clichés about young Americans,” Antonioni had said. He failed. “Corny? You bet your ass it’s corny,” wrote John Burks in a ruthless but romantic review for Rolling Stone. “Antonioni has constructed his movie of so many lame metaphors and bad puns that it’s staggering.” Mark, ever authentic, went on the Dick Cavett Show and told the host, who hadn’t seen the movie, to save his money. Antonioni’s film was mired in nostalgia for a time that was still unfolding. But, just maybe, the golden gobs of idealism on the director’s lens made for a truer document of modernism’s gasping dreams and its aleatory fallout than he realized. Even its critics admit the gangly plot is slung between images of scintillating pathos and splendor: the opening scene of student radicals rapping in a classroom; the final sequence of a mansion crammed with consumer goods exploding in tingling slow motion; and the centerpiece, some 20 minutes of striking Death Valley landscape, Mark and Daria flirting through it like pretext. The actors’ lives, too, bear out images to punctuate the era. With the money and fame from Zabriskie Point, Mark was finally let into Lyman’s cult. Daria, his lover for a time, followed him to Boston, but didn’t dig it, and went back to the Bay Area. In 1973, Mark was arrested after a botched bank heist (he claimed it was the closest he could get to robbing Richard Nixon), and died in prison two years later in a suspicious weightlifting accident. Meanwhile, Daria married and divorced Dennis Hopper, star of Easy Rider, the kind of era-defining movie Antonioni had wanted Zabriskie Point to be.

*

Zabriskie Point is an alien outcropping near the east rim of Death Valley that overlooks the sepulchral beauty of wind-hardened canyons of yellow- and rose-gold sand. On any given morning, dozens of photographers gather there to make images of the sunrise. Many leave after just a few seconds of light: evidently, the best part is over quickly. Antonioni’s film meanders through this scenery for around 20 minutes. As Antonioni said in 1969, during production, “A boy and a girl meet. They talk. That’s all. Everything that happens before they meet is a prologue. Everything that happens after they talk is an epilogue.” The film’s rocky plot is a vehicle for getting Antonioni’s two stars untangled from Los Angeles (prologue), beyond what he saw as a soulless commercial wasteland of billboards and fast food stands and facades, and out to the real stuff: mounds of pulverized minerals. Everything on either side of Zabriskie Point is the politics of the 1960s, the Movement, the ravages of capitalism and the pigs. In other words, the politics of landscape—conquest, development, when the freedom of the desert was not the freedom to fuck in a national park but to claim, to exploit, to “mine.” They talk, saying nothing much, keeping time, as politics presses in. Suddenly a hundred other couples, like ghosts, nip and prod and pleasure each other in the dust. Then, it’s over. Even in 1970, even to Antonioni’s dazzled eye, the drift into the desert felt predictable. “I always knew it would be like this,” says Mark, post-coital. Maybe he means sex. Maybe he means the desert, or Hollywood film. Maybe he means the revolution. The phrase, cynical and beatific, hangs over the film like haze.

snip

"ZABRISKIE POINT"

Richard Brody on Michelangelo Antonioni's "Zabriskie Point" (1970).

https://www.newyorker.com/video/watch/zabriskie-point

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

0 replies, 434 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (2)

ReplyReply to this post