Religion

Related: About this forumUtopia: Daring to dream

January 8, 2017

Ruth Potts

Utopian dreams are a catalyst for the oppressed and marginalised. They remind us that other worlds are possible, and give us the hope, which, in the words of the author and activist Rebecca Solnit, makes action possible. Utopia is immediate and polemical – a prompt to dream and to act. It effects immediate changes in the real world, now.

Recent thinking in anthropology suggests that it was the development of our imaginations, and then consequently our ability to construct social structures and institutions, that allowed complex societies to evolve. Large societies and the glue that holds them together are all made up: nations, tribes, religion, money and the law-enforcing powers of a judge are arbitrary products of our collective creative thought. There are times, speculates London-based anthropologist Maurice Bloch, when the arbitrariness of those systems becomes apparent. Examining some of the changes currently taking place in the world, he believes that we are developing ‘an awareness of the imaginary nature of the institutions that we live in’.

Thomas More’s Utopia, first published 500 years ago this December, provides a timely reminder of the enduring power of imagination and its ability to shape the world we live in. More’s utopia followed a well-known trope: the traveller who recounts their experience of a land in which a range of problems have been solved. It’s a format that exists or has existed in every culture in some form. Plato’s Republic, which More had read and was influenced by, is often cited as one of the earliest utopian works.

There are also germs of utopian fiction in ancient descriptions of paradise, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, the Elysian Fields or the lost city of Atlantis. We glimpse utopia in classical Greek and Latin literature, the Old Testament, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Hinduism. Tao Hua Yuan, or Peach Blossom Spring, a fable by T’ao Yuan-Ming (365-427) set its utopian world in a hidden grove behind peach blossom trees. There are oral utopian traditions among Aboriginal people in Australia, the first nations in Canada, the Maori in New Zealand, and Native Americans. What More did was not new, but by naming his imaginary world he gave the concept form, shape and an irresistible ambiguity (meaning both no place and good place) that has captured the human imagination ever since.

http://www.redpepper.org.uk/utopia-daring-to-dream/

global1

(25,241 posts)when Trump placed his hand on the Bible to take the oath of office on Jan 20th - that they slapped handcuffs on him and frogmarched him out of Washington DC.

rug

(82,333 posts)We can hope it happens within his term.

Jim__

(14,075 posts)I understand the OP to be talking about looking toward a utopia to get ideas about how life can be improved and then approaching it incrementally. Trying to achieve utopia through one giant step can be extremely dangerous.

The January 19th issue of The New York Review of Books reviews the book The Killing Wind: A Chinese County’s Descent into Madness During the Cultural Revolution by Tan Hecheng, translated from the Chinese by Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian. As noted in the excerpt, the Chinese Cultural Revolution was a part of Mao's attempt to achieve a utopia.

An excerpt:

[/center]

[/center]

…

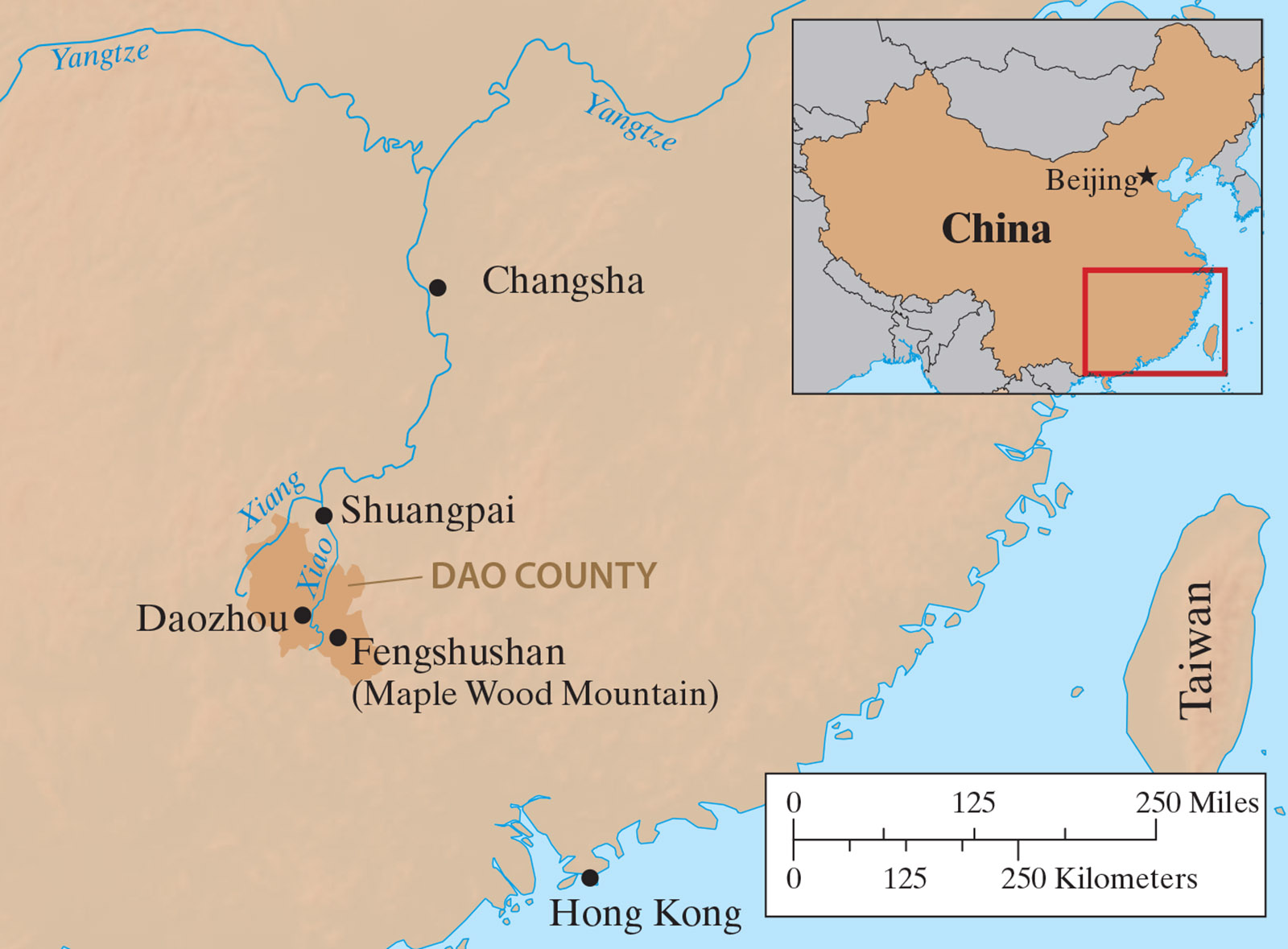

Fifty years ago, these currents transported another cargo: bloated corpses. For several weeks in August and September 1967, more than nine thousand people were murdered in this region. The epicenter of the killings was Dao County (Daoxian), which the Xiao River bisects on its way north. About half the victims were killed in this district of four hundred thousand people, some clubbed to death and thrown into limestone pits, others tossed into cellars full of sweet potatoes where they suffocated. Many were tied together in bundles around a charge of quarry explosives. These victims were called “homemade airplanes” because their body parts flew over the fields. But most victims were simply bludgeoned to death with agricultural tools—hoes, carrying poles, and rakes—and then tossed into the waterways that flow into the Xiao.

In the county seat of Daozhou, observers on the shoreline counted one hundred corpses flowing past per hour. Children danced along the banks competing to find the most bodies. Some were bound together with wire strung through their collarbones, their swollen carcasses swirling in daisy chains downstream, their eyes and lips already eaten away by fish. Eventually the cadavers’ progress was halted by the Shuangpai dam where they clogged the hydropower generators. It took half a year to clear the turbines and two years before locals would eat fish again.

For decades, these murders have been a little-known event in China. When mentioned at all, they tended to be explained away as individual actions that spun out of control during the heat of the Cultural Revolution—the decade-long campaign launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 to destroy enemies and achieve a utopia. Dao County was portrayed as remote, backward, and poor. The presence of the non-Chinese Yao minority there was also sometimes mentioned as a racist way of explaining what happened: those minorities, some Han Chinese say, are only half civilized anyway, and who knows what they might do when the authorities aren’t looking?

All of these explanations are wrong. Dao County is a center of Chinese civilization, the birthplace of great philosophers and calligraphers. The killers were almost all Chinese who murdered other Chinese. And the killings were not random: instead they were acts of genocide aimed at eliminating a class of people declared to be subhuman. That class consisted of make-believe landlords, nonexistent spies, and invented insurrectionists. Far from being the work of frenzied peasants, the killings were organized by committees of Communist Party cadres in the region’s towns, who ordered the murders to be carried out in remote areas. To make sure revenge would be difficult, officials ordered the slaughter of entire families, including infants.

more …

rug

(82,333 posts)I don't think the author is necessarily talking about approaching utopia incrementally. As she describes it, utopia is not a static concept out there to be reached. She describes it as a rather vague better place, the roots of which are already present in society.

That said, as socialists they are well aware of the dangers of a cult of personality, one of the driving forces behind the Cultural Revolution. Red Pepper magazine also has contingents of various European Green Parties so it doesn't strike me as calling for an immediate violent revolution to achieve a defined and specific Utopia.

At this point, it looks more aspirational than revolutionary.

The reason I posted it here was this:

It's a thoughtful way to gauge groups seeking to transform society, be those groups ISIS, the Franciscans or the Red Brigades.

Jim__

(14,075 posts)... the beginning of complex society.

Hunter-gatherer societies were egalitarian and food was shared equitably and immediately. Agriculture brought storable surpluses, inequitable distribution, rich targets for roving bands of brigands, rich and powerful owners of these surpluses, and the division of labor to perform the separate tasks required by an agricultural community. Some of those tasks amounted to drudgery. I imagine, along with drudgery came a longing for some way to avoid it - a desire for some type of utopia.

The dawning of the robot era definitely allows us to eliminate a lot of drudgery. Coupled with a sensible distribution system, this could be a big step toward utopia. I don’t, however, see much hope for a sensible distribution system.

Bretton Garcia

(970 posts)"From each according to their abilities; to each according to their needs."