Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Mr. Scorpio

Mr. Scorpio's Journal

Mr. Scorpio's Journal

March 29, 2016

http://mic.com/articles/139279/donald-trump-asking-twitter-what-s-in-reporter-michelle-fields-hand-totally-backfires?utm_source=policymicTBLR&utm_medium=main&utm_campaign=social#.kQiFyIc2p

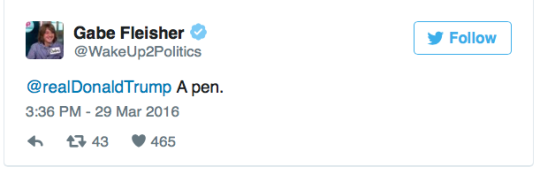

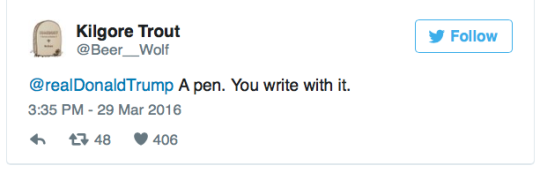

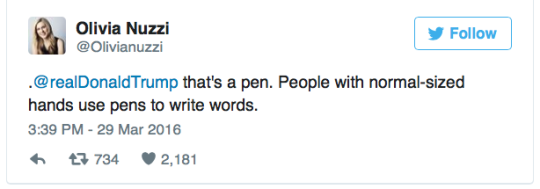

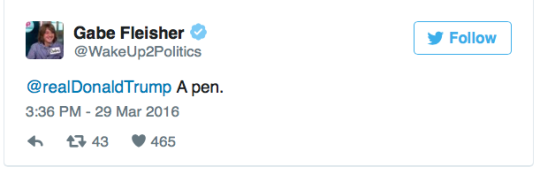

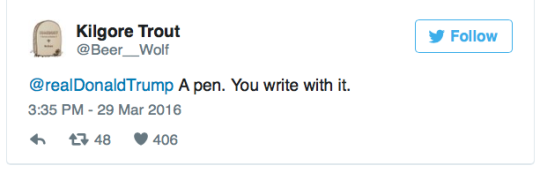

About something that a person with normal sized hands is holding...

http://mic.com/articles/139279/donald-trump-asking-twitter-what-s-in-reporter-michelle-fields-hand-totally-backfires?utm_source=policymicTBLR&utm_medium=main&utm_campaign=social#.kQiFyIc2p

March 28, 2016

Robert Jensen

Here's what white privilege sounds like: I'm sitting in my University of Texas office, talking to a very bright and very conservative white student about affirmative action in college admissions, which he opposes and I support. The student says he wants a level playing field with no unearned advantages for anyone. I ask him whether he thinks that being white has advantages in the United States. Have either of us, I ask, ever benefited from being white in a world run mostly by white people? Yes, he concedes, there is something real and tangible we could call white privilege.

So, if we live in a world of white privilege – unearned white privilege - how does that affect your notion of a level playing field? I asked. He paused for a moment and said, "That really doesn't matter." That statement, I suggested to him, reveals the ultimate white privilege: The privilege to acknowledge that you have unearned privilege but to ignore what it means. That exchange led me to rethink the way I talk about race and racism with students. It drove home the importance of confronting the dirty secret that we white people carry around with us every day: in a world of white privilege, some of what we have is unearned. I think much of both the fear and anger that comes up around discussions of affirmative action has its roots in that secret. So these days, my goal is to talk open and honestly about white supremacy and white privilege.

White privilege, like any social phenomenon, is complex. In a white supremacist culture, all white people have privilege, whether or not they are overtly racist themselves. There are general patterns, but such privilege plays out differently depending on context and other aspects of one's identity (in my case, being male gives me other kinds of privilege). Rather than try to tell others how white privilege has played out in their lives, I talk about how it has affected me.

I am as white as white gets in this country. I am of northern European heritage and I was raised in North Dakota, one of the whitest states in the country. I grew up in a virtually all-white world surrounded by racism, both personal and institutional. Because I didn't live near a reservation, I didn't even have exposure to the state's only numerically significant nonwhite population, American Indians.

http://occupywallstreet.net/story/white-privilege-shapes-us

White Privilege Shapes The U.S.

Robert Jensen

Here's what white privilege sounds like: I'm sitting in my University of Texas office, talking to a very bright and very conservative white student about affirmative action in college admissions, which he opposes and I support. The student says he wants a level playing field with no unearned advantages for anyone. I ask him whether he thinks that being white has advantages in the United States. Have either of us, I ask, ever benefited from being white in a world run mostly by white people? Yes, he concedes, there is something real and tangible we could call white privilege.

So, if we live in a world of white privilege – unearned white privilege - how does that affect your notion of a level playing field? I asked. He paused for a moment and said, "That really doesn't matter." That statement, I suggested to him, reveals the ultimate white privilege: The privilege to acknowledge that you have unearned privilege but to ignore what it means. That exchange led me to rethink the way I talk about race and racism with students. It drove home the importance of confronting the dirty secret that we white people carry around with us every day: in a world of white privilege, some of what we have is unearned. I think much of both the fear and anger that comes up around discussions of affirmative action has its roots in that secret. So these days, my goal is to talk open and honestly about white supremacy and white privilege.

White privilege, like any social phenomenon, is complex. In a white supremacist culture, all white people have privilege, whether or not they are overtly racist themselves. There are general patterns, but such privilege plays out differently depending on context and other aspects of one's identity (in my case, being male gives me other kinds of privilege). Rather than try to tell others how white privilege has played out in their lives, I talk about how it has affected me.

I am as white as white gets in this country. I am of northern European heritage and I was raised in North Dakota, one of the whitest states in the country. I grew up in a virtually all-white world surrounded by racism, both personal and institutional. Because I didn't live near a reservation, I didn't even have exposure to the state's only numerically significant nonwhite population, American Indians.

http://occupywallstreet.net/story/white-privilege-shapes-us

March 28, 2016

Chris Boeskool

03/14/2016 01:18 pm ET | Updated Mar 14, 2016

I’ve never been punched in the face. Not in an actual fight, at least. I’m not much of a fighter, I suppose... more of an “arguer.” I don’t think I’m “scared” to get into a fight, necessarily — there have been many times I have put myself in situations where a physical fight could easily have happened.

I just can’t see myself ever being the guy who throws the first punch, and I’m usually the kind of guy who DE-escalates things with logic or humor. And one of the things about being that sort of person, is that the other sort of guy — the sort who jumps into fights quickly — tends to not really be a big fan of me. Not when he first meets me, at least. They usually like me later. Not always. You can’t win ‘em all...

When I moved to Nashville, I didn’t really know anyone. I got a job as a server on my second day here. And before long, I was one of the servers the management favored, which meant I got better shifts, better sections and better money.

About nine months after I had been there, a new guy started. We instantly disliked each other. He didn’t like my smart mouth, and I didn’t like how he walked in and immediately acted like he owned the place. He carried himself with this annoying confidence — like it was his world, and he would tolerate our being in it, as long as we stayed out of his damn way.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/chris-boeskool/when-youre-accustomed-to-privilege_b_9460662.html

‘When You’re Accustomed to Privilege, Equality Feels Like Oppression’

Chris Boeskool

03/14/2016 01:18 pm ET | Updated Mar 14, 2016

I’ve never been punched in the face. Not in an actual fight, at least. I’m not much of a fighter, I suppose... more of an “arguer.” I don’t think I’m “scared” to get into a fight, necessarily — there have been many times I have put myself in situations where a physical fight could easily have happened.

I just can’t see myself ever being the guy who throws the first punch, and I’m usually the kind of guy who DE-escalates things with logic or humor. And one of the things about being that sort of person, is that the other sort of guy — the sort who jumps into fights quickly — tends to not really be a big fan of me. Not when he first meets me, at least. They usually like me later. Not always. You can’t win ‘em all...

When I moved to Nashville, I didn’t really know anyone. I got a job as a server on my second day here. And before long, I was one of the servers the management favored, which meant I got better shifts, better sections and better money.

About nine months after I had been there, a new guy started. We instantly disliked each other. He didn’t like my smart mouth, and I didn’t like how he walked in and immediately acted like he owned the place. He carried himself with this annoying confidence — like it was his world, and he would tolerate our being in it, as long as we stayed out of his damn way.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/chris-boeskool/when-youre-accustomed-to-privilege_b_9460662.html

March 28, 2016

(Image: Markian Lozowchuk)

BY DESMOND COLE | APRIL 21, 2015 AT 12:28 PM

The summer I was nine, my teenage cousin Sana came from England to visit my family in Oshawa. He was tall, handsome and obnoxious, the kind of guy who could palm a basketball like Michael Jordan. I was his shadow during his visit, totally in awe of his confidence—he was always saying something clever to knock me off balance.

One day, we took Sana and his parents on a road trip to Niagara Falls. Just past St. Catharines, Sana tossed a dirty tissue out the window. Within seconds, we heard a siren: a cop had been driving behind us, and he immediately pulled us onto the shoulder. A hush came over the car as the stocky officer strode up to the window and asked my dad if he knew why we’d been stopped. “Yes,” my father answered, his voice shaky, like a child in the principal’s office. My dad isn’t a big man, but he always cut an imposing figure in our household. This was the first time I realized he could be afraid of something. “He’s going to pick it up right now,” he assured the officer nervously, as Sana exited the car to retrieve the garbage. The cop seemed casually uninterested, but everyone in the car thrummed with tension, as if they were bracing for something catastrophic. After Sana returned, the officer let us go. We drove off, overcome with silence until my father finally exploded. “You realize everyone in this car is black, right?” he thundered at Sana. “Yes, Uncle,” Sana whispered, his head down and shoulders slumped. That afternoon, my imposing father and cocky cousin had trembled in fear over a discarded Kleenex.

My parents immigrated to Canada from Freetown, Sierra Leone, in the mid-1970s. I was born in Red Deer, Alberta, and soon after, we moved to Oshawa, where my father was a mental health nurse and my mother a registered nurse who worked with the elderly. Throughout my childhood, my parents were constantly lecturing me about respecting authority, working hard and preserving our family’s good name. They made it clear that although I was the same as my white peers, I would have to try harder and achieve more just to keep up. I tried to ignore what they said about my race, mostly because it seemed too cruel to be true.

In high school, I threw myself into extra-curricular activities—student council, choir, tennis, soccer, fundraising drives for local charities—and I graduated valedictorian of my class. Despite my misgivings about my parents’ advice, I was proud to be living up to their expectations. In 2001, I earned admission to Queen’s University. I was enticed by the isolated, scenic campus—it looked exactly like the universities I’d seen in movies, with stately buildings and waterfront views straight out of Dead Poets Society. When I told my older sister, who was studying sociology at Western, she furrowed her brow. “It’s so white,” she bristled. That didn’t matter much to me: Oshawa was just as white as Kingston, and I was used to being the only black kid in the room. I wasn’t going to let my race dictate my future.

http://torontolife.com/city/life/skin-im-ive-interrogated-police-50-times-im-black/

The Skin I’m In: I’ve been interrogated by police more than 50 times—all because I’m black

(Image: Markian Lozowchuk)

BY DESMOND COLE | APRIL 21, 2015 AT 12:28 PM

The summer I was nine, my teenage cousin Sana came from England to visit my family in Oshawa. He was tall, handsome and obnoxious, the kind of guy who could palm a basketball like Michael Jordan. I was his shadow during his visit, totally in awe of his confidence—he was always saying something clever to knock me off balance.

One day, we took Sana and his parents on a road trip to Niagara Falls. Just past St. Catharines, Sana tossed a dirty tissue out the window. Within seconds, we heard a siren: a cop had been driving behind us, and he immediately pulled us onto the shoulder. A hush came over the car as the stocky officer strode up to the window and asked my dad if he knew why we’d been stopped. “Yes,” my father answered, his voice shaky, like a child in the principal’s office. My dad isn’t a big man, but he always cut an imposing figure in our household. This was the first time I realized he could be afraid of something. “He’s going to pick it up right now,” he assured the officer nervously, as Sana exited the car to retrieve the garbage. The cop seemed casually uninterested, but everyone in the car thrummed with tension, as if they were bracing for something catastrophic. After Sana returned, the officer let us go. We drove off, overcome with silence until my father finally exploded. “You realize everyone in this car is black, right?” he thundered at Sana. “Yes, Uncle,” Sana whispered, his head down and shoulders slumped. That afternoon, my imposing father and cocky cousin had trembled in fear over a discarded Kleenex.

My parents immigrated to Canada from Freetown, Sierra Leone, in the mid-1970s. I was born in Red Deer, Alberta, and soon after, we moved to Oshawa, where my father was a mental health nurse and my mother a registered nurse who worked with the elderly. Throughout my childhood, my parents were constantly lecturing me about respecting authority, working hard and preserving our family’s good name. They made it clear that although I was the same as my white peers, I would have to try harder and achieve more just to keep up. I tried to ignore what they said about my race, mostly because it seemed too cruel to be true.

In high school, I threw myself into extra-curricular activities—student council, choir, tennis, soccer, fundraising drives for local charities—and I graduated valedictorian of my class. Despite my misgivings about my parents’ advice, I was proud to be living up to their expectations. In 2001, I earned admission to Queen’s University. I was enticed by the isolated, scenic campus—it looked exactly like the universities I’d seen in movies, with stately buildings and waterfront views straight out of Dead Poets Society. When I told my older sister, who was studying sociology at Western, she furrowed her brow. “It’s so white,” she bristled. That didn’t matter much to me: Oshawa was just as white as Kingston, and I was used to being the only black kid in the room. I wasn’t going to let my race dictate my future.

http://torontolife.com/city/life/skin-im-ive-interrogated-police-50-times-im-black/

Profile Information

Member since: 2002Number of posts: 73,630