Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

April 16, 2019

107 Years Ago Today; Harriet Quimby becomes first Woman to fly across English Channel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_Quimby

Harriet Quimby (May 11, 1875 – July 1, 1912) was an early American aviator and a movie screenwriter. In 1911, she was awarded a U.S. pilot's certificate by the Aero Club of America, becoming the first woman to gain a pilot's license in the United States. In 1912, she became the first woman to fly across the English Channel. Although Quimby lived only to the age of 37, she influenced the role of women in aviation.

Early life and early career

She was born on May 11, 1875 in Arcadia Township, Manistee County, Michigan. After her family moved to San Francisco, California, in the early 1900s, she became a journalist. Harriet Quimby's public life began in 1902, when she began writing for the San Francisco Dramatic Review and also contributed to the Sunday editions of the San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Call. She moved to Manhattan, New York City in 1903 to work as a theater critic for Leslie's Illustrated Weekly and more than 250 of her articles were published over a nine-year period. Quimby continued to write for Leslie's even when touring with airshows, recounting her adventures in a series of articles. Totally committed to her new passion, the dedicated journalist and aviator avidly promoted the economic potential of commercial aviation and touted flying as an ideal sport for women.

Quimby became interested in aviation in 1910, when she attended the Belmont Park International Aviation Tournament in Elmont, New York. There she met John Moisant, a well-known aviator and operator of a flight school, and his sister Matilde.

On August 1, 1911, she took her pilot's test and became the first U.S. woman to earn an Aero Club of America aviator's certificate. Matilde Moisant soon followed and became the second.

Due to the absence of any official birth certificate, many communities have claimed her over the years.

Aviation

After earning her license, the "Dresden China Aviatrix" or "China Doll," as the press called her because of her petite stature and fair skin, moved to capitalize on her new notoriety. Pilots could earn as much as $1,000 per performance, and prize money for a race could go as high as $10,000 or more. Quimby joined the Moisant International Aviators, an exhibition team, and made her professional debut, earning $1,500, in a night flight over Staten Island before a crowd of almost 20,000 spectators. As one of the country's few female pilots, she capitalized on her femininity by wearing trousers tucked into high lace boots accentuated by a plum-colored satin blouse, necklace, and antique bracelet. She drew crowds whenever she competed in cross-country meets and races. As part of the exhibition team, she showcased her talents around the United States and even went to Mexico City at the end of 1911 to participate in aviation activities held in honor of the inauguration of President Francisco Madero.

<snip>

English Channel flight

On April 16, 1912, Quimby took off from Dover, England, en route to Calais, France, and made the flight in 59 minutes, landing about 25 miles (40 km) from Calais on a beach in Équihen-Plage, Pas-de-Calais. She became the first woman to pilot an aircraft across the English Channel. Her accomplishment received little media attention, however, as the sinking of the RMS Titanic the day before consumed the interest of the public and filled newspapers.

Death

On July 1, 1912, she flew in the Third Annual Boston Aviation Meet at Squantum, Massachusetts. Although she had obtained her ACA certificate to be allowed to participate in ACA events, the Boston meet was an unsanctioned contest. Quimby flew out to Boston Light in Boston Harbor at about 3,000 feet, then returned and circled the airfield. William A.P. Willard, the organizer of the event and father of the aviator Charles Willard, was a passenger in her brand-new two-seat Bleriot monoplane. At an altitude of 1,000 feet (300 m) the aircraft unexpectedly pitched forward for reasons still unknown. Both Willard and Quimby were ejected from their seats and fell to their deaths, while the plane "glided down and lodged itself in the mud".

Harriet Quimby was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York. The following year her remains were moved to the Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

</snip>

Harriet Quimby (May 11, 1875 – July 1, 1912) was an early American aviator and a movie screenwriter. In 1911, she was awarded a U.S. pilot's certificate by the Aero Club of America, becoming the first woman to gain a pilot's license in the United States. In 1912, she became the first woman to fly across the English Channel. Although Quimby lived only to the age of 37, she influenced the role of women in aviation.

Early life and early career

She was born on May 11, 1875 in Arcadia Township, Manistee County, Michigan. After her family moved to San Francisco, California, in the early 1900s, she became a journalist. Harriet Quimby's public life began in 1902, when she began writing for the San Francisco Dramatic Review and also contributed to the Sunday editions of the San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Call. She moved to Manhattan, New York City in 1903 to work as a theater critic for Leslie's Illustrated Weekly and more than 250 of her articles were published over a nine-year period. Quimby continued to write for Leslie's even when touring with airshows, recounting her adventures in a series of articles. Totally committed to her new passion, the dedicated journalist and aviator avidly promoted the economic potential of commercial aviation and touted flying as an ideal sport for women.

Quimby became interested in aviation in 1910, when she attended the Belmont Park International Aviation Tournament in Elmont, New York. There she met John Moisant, a well-known aviator and operator of a flight school, and his sister Matilde.

On August 1, 1911, she took her pilot's test and became the first U.S. woman to earn an Aero Club of America aviator's certificate. Matilde Moisant soon followed and became the second.

Due to the absence of any official birth certificate, many communities have claimed her over the years.

Aviation

After earning her license, the "Dresden China Aviatrix" or "China Doll," as the press called her because of her petite stature and fair skin, moved to capitalize on her new notoriety. Pilots could earn as much as $1,000 per performance, and prize money for a race could go as high as $10,000 or more. Quimby joined the Moisant International Aviators, an exhibition team, and made her professional debut, earning $1,500, in a night flight over Staten Island before a crowd of almost 20,000 spectators. As one of the country's few female pilots, she capitalized on her femininity by wearing trousers tucked into high lace boots accentuated by a plum-colored satin blouse, necklace, and antique bracelet. She drew crowds whenever she competed in cross-country meets and races. As part of the exhibition team, she showcased her talents around the United States and even went to Mexico City at the end of 1911 to participate in aviation activities held in honor of the inauguration of President Francisco Madero.

<snip>

English Channel flight

On April 16, 1912, Quimby took off from Dover, England, en route to Calais, France, and made the flight in 59 minutes, landing about 25 miles (40 km) from Calais on a beach in Équihen-Plage, Pas-de-Calais. She became the first woman to pilot an aircraft across the English Channel. Her accomplishment received little media attention, however, as the sinking of the RMS Titanic the day before consumed the interest of the public and filled newspapers.

Death

On July 1, 1912, she flew in the Third Annual Boston Aviation Meet at Squantum, Massachusetts. Although she had obtained her ACA certificate to be allowed to participate in ACA events, the Boston meet was an unsanctioned contest. Quimby flew out to Boston Light in Boston Harbor at about 3,000 feet, then returned and circled the airfield. William A.P. Willard, the organizer of the event and father of the aviator Charles Willard, was a passenger in her brand-new two-seat Bleriot monoplane. At an altitude of 1,000 feet (300 m) the aircraft unexpectedly pitched forward for reasons still unknown. Both Willard and Quimby were ejected from their seats and fell to their deaths, while the plane "glided down and lodged itself in the mud".

Harriet Quimby was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York. The following year her remains were moved to the Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

</snip>

April 15, 2019

99 Years Ago Today; An armed robbery at the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, MA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacco_and_Vanzetti

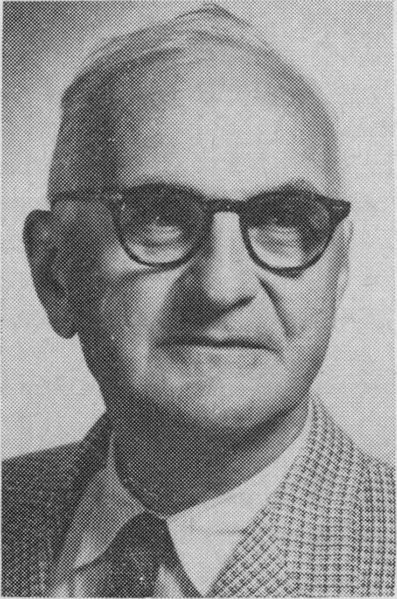

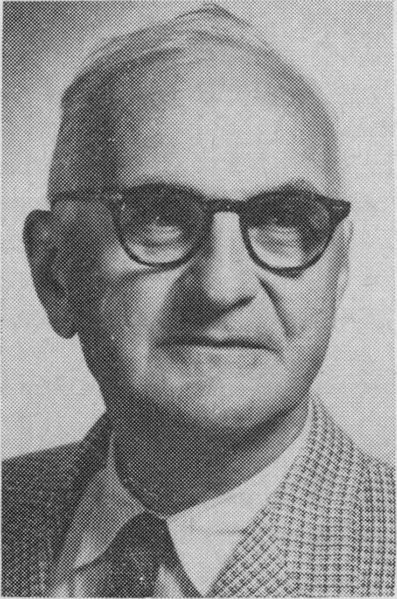

Controversial anarchist trial defendants Bartolomeo Vanzetti (left) and Nicola Sacco

Nicola Sacco (April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian-born American anarchists who were controversially convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during the April 15, 1920 armed robbery of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts, United States. Seven years later, they were electrocuted in the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison. Both men adhered to an anarchist movement.

After a few hours' deliberation on July 14, 1921, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of first-degree murder and they were sentenced to death by the trial judge. Anti-Italianism, anti-immigrant bias, and anti-right political motives were suspected as having heavily influenced the verdict. A series of appeals followed, funded largely by the private Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee. The appeals were based on recanted testimony, conflicting ballistics evidence, a prejudicial pre-trial statement by the jury foreman, and a confession by an alleged participant in the robbery. All appeals were denied by trial judge Webster Thayer and also later denied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. By 1926, the case had drawn worldwide attention. As details of the trial and the men's suspected innocence became known, Sacco and Vanzetti became the center of one of the largest causes célèbres in modern history. In 1927, protests on their behalf were held in every major city in North America and Europe, as well as in Tokyo, Sydney, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, and Auckland.

Celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their pardon or for a new trial. Harvard law professor and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter argued for their innocence in a widely read Atlantic Monthly article that was later published in book form. The two were scheduled to die in April 1927, accelerating the outcry. Responding to a massive influx of telegrams urging their pardon, Massachusetts governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-man commission to investigate the case. After weeks of secret deliberation that included interviews with the judge, lawyers, and several witnesses, the commission upheld the verdict. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair just after midnight on August 23, 1927. Subsequent riots destroyed property in Paris, London, and other cities.

Investigations in the aftermath of the executions continued throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The publication of the men's letters, containing eloquent professions of innocence, intensified belief in their wrongful execution. Additional ballistics tests and incriminating statements by the men's acquaintances have clouded the case. On August 23, 1977—the 50th anniversary of the executions—Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names".

<snip>

Robbery

The Slater-Morrill Shoe Company factory was located on Pearl Street in Braintree, Massachusetts. On April 15, 1920, two men were robbed and killed while transporting the company's payroll in two large steel boxes to the main factory. One of them, Alessandro Berardelli —a security guard— was shot four times as he reached for his hip-holstered .38-caliber, Harrington & Richardson revolver; his gun was not recovered from the scene. The other man, Frederick Parmenter—a paymaster who was unarmed—was shot twice: once in the chest and a second time, fatally, in the back as he attempted to flee. The robbers seized the payroll boxes and escaped in a stolen dark blue Buick that sped up and was carrying several other men.

As the car was being driven away, the robbers fired wildly at company workers nearby. A coroner's report and subsequent ballistic investigation revealed that six bullets removed from the murdered men's bodies were of .32 automatic (ACP) caliber. Five of these .32-caliber bullets were all fired from a single semi-automatic pistol, a .32-caliber Savage Model 1907, which used a particularly narrow-grooved barrel rifling with a right-hand twist. Two of the bullets were recovered from Berardelli's body. Four .32 automatic brass shell casings were found at the murder scene, manufactured by one of three firms: Peters, Winchester, or Remington. The Winchester cartridge case was of a relatively obsolete cartridge loading, which had been discontinued from production some years earlier. Two days after the robbery, police located the robbers' Buick; several 12-gauge shotgun shells were found on the ground nearby.

Arrests and indictment

An earlier attempted robbery of another shoe factory occurred on December 24, 1919 in Bridgewater, Massachusetts by people identified as Italian who used a car that was seen escaping to Cochesett in West Bridgewater. Police speculated that Italian anarchists perpetrated the robberies to finance their activities. Bridgewater police chief Michael E. Stewart suspected that known Italian anarchist Ferruccio Coacci was involved. Stewart discovered that Mario Buda (aka 'Mike' Boda) lived with Coacci.

On April 16—one day after the Braintree robbery-murders—the Federal Immigration Service (FIS) called Chief Stewart to discuss Galleanist and anarchist Coacci, whom Stewart had arrested on their behalf two years earlier. Coacci was slated for deportation on April 15, 1920, the day of the Braintree holdup, but telephoned with the excuse that his wife was ill. The FIS asked Stewart to investigate Coacci's excuse for failing to report for deportation on April 15. On April 16, officers discovered Coacci at home and determined that he had given a false alibi for not showing up for deportation. They offered him another week, but Coacci declined and left for Italy on April 18, 1920.

When Chief Stewart later arrived at the Coacci home, Coacci was missing but they found Buda. When he was questioned, Buda said that Coacci owned a .32 Savage automatic pistol, which he kept in the kitchen. A search of the kitchen did not locate the gun, but Stewart found a manufacturer's technical diagram for a Model 1907 .32 Savage automatic pistol – the exact pistol type and caliber used to shoot Parmenter and Berardelli – in a kitchen drawer. Stewart asked Buda if he owned a gun, and the man produced a .32-caliber Spanish-made automatic pistol. Buda told police that he owned a 1914 Overland automobile, which was being repaired. The car was delivered for repairs four days after the Braintree crimes, but it was old and apparently had not been run for five months. Tire tracks were seen near the abandoned Buick getaway car, and Chief Stewart surmised that two cars had been used in the getaway, and that Buda's car might have been the second car. The garage proprietor who was repairing Buda's vehicle was instructed to call the police if anyone came to pick up the car.

When Stewart discovered that Coacci had worked for both shoe factories that had been robbed, he returned with the Bridgewater police. Coacci had since left for Italy with his family along with his possessions, and Buda had just escaped.

On May 5, 1920, Mario Buda arrived at the garage with three other men, later identified as Sacco, Vanzetti, and Riccardo Orciani. The four men knew each other well; Buda would later call Sacco and Vanzetti "the best friends I had in America." Police were alerted, but the men left. Buda escaped and did not resurface until 1928 in Italy.

Sacco and Vanzetti boarded a streetcar, but were tracked down and soon arrested. When searched by police, both denied owning any guns, but were found to be holding loaded pistols. Sacco was found to have an Italian passport, anarchist literature, a loaded .32 Colt Model 1903 automatic pistol, and twenty-three .32 Automatic cartridges in his possession; several of those bullet cases were of the same obsolescent type as the empty Winchester .32 casing found at the crime scene, and others were manufactured by the firms of Peters and Remington, much like other casings found at the scene. Vanzetti had four 12-gauge shotgun shells and a five-shot nickel-plated .38-caliber Harrington & Richardson revolver similar to the .38 carried by Berardelli, the slain Braintree guard, whose weapon was not found at the scene of the crime. When they were questioned, the pair denied any connection to anarchists.

Orciani was arrested May 6, but gave the alibi that he had been at work on the day of both crimes. Sacco had been at work on the day of the Bridgewater crimes but said that he had the day off on April 15—the day of the Braintree crimes— and was charged with those murders. The self-employed Vanzetti had no such alibis and was charged for the attempted robbery and attempted murder in Bridgewater and the robbery and murder in the Braintree crimes. Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime of murder on May 5, 1920 and indicted four months later on September 14.

Following Sacco and Vanzetti's indictment for murder for the Braintree robbery, Galleanists and anarchists in the United States and abroad began a campaign of violent retaliation. Two days later on September 16, 1920, Mario Buda allegedly orchestrated the Wall Street bombing, where a time-delay dynamite bomb packed with heavy iron sash-weights in a horse-drawn cart exploded, killing 38 people and wounding 134. In 1921, a booby trap bomb mailed to the American ambassador in Paris exploded, wounding his valet. For the next six years, bombs exploded at other American embassies all over the world.

<snip>

Sentencing

On April 9, 1927, Judge Thayer heard final statements from Sacco and Vanzetti. In a lengthy speech Vanzetti said:

Thayer declared that the responsibility for the conviction rested solely with the jury's determination of guilt. "The Court has absolutely nothing to do with that question." He sentenced each of them to "suffer the punishment of death by the passage of a current of electricity through your body" during the week beginning July 10. He twice postponed the execution date while the governor considered requests for clemency.[130]

On May 10, a package bomb addressed to Governor Fuller was intercepted in the Boston post office.

Clemency appeal and the Governor's Advisory Committee

In response to public protests that greeted the sentencing, Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller faced last-minute appeals to grant clemency to Sacco and Vanzetti. On June 1, 1927, he appointed an Advisory Committee of three: President Abbott Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, President Samuel Wesley Stratton of MIT, and Probate Judge Robert Grant. They were presented with the task of reviewing the trial to determine whether it had been fair. Lowell's appointment was generally well received, for though he had controversy in his past, he had also at times demonstrated an independent streak. The defense attorneys considered resigning when they determined that the Committee was biased against the defendants, but some of the defendants' most prominent supporters, including Harvard Law Professor Felix Frankfurter and Judge Julian W. Mack of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, persuaded them to stay because Lowell "was not entirely hopeless."

One of the defense attorneys, though ultimately very critical of the Committee's work, thought the Committee members were not really capable of the task the Governor set for them:

No member of the Committee had the essential sophistication that comes with experience in the trial of criminal cases. ... The high positions in the community held by the members of the Committee obscured the fact that they were not really qualified to perform the difficult task assigned to them.

He also thought that the Committee, particularly Lowell, imagined it could use its fresh and more powerful analytical abilities to outperform the efforts of those who had worked on the case for years, even finding evidence of guilt that professional prosecutors had discarded.

Grant was another establishment figure, a probate court judge from 1893 to 1923 and an Overseer of Harvard University from 1896 to 1921, and the author of a dozen popular novels. Some criticized Grant's appointment to the Committee, with one defense lawyer saying he "had a black-tie class concept of life around him," but Harold Laski in a conversation at the time found him "moderate." Others cited evidence of xenophobia in some of his novels, references to "riff-raff" and a variety of racial slurs. His biographer allows that he was "not a good choice," not a legal scholar, and handicapped by age. Stratton, the one member who was not a "Boston Brahmin," maintained the lowest public profile of the three and hardly spoke during its hearings.

In their earlier appeals, the defense was limited to the trial record. The Governor's Committee, however, was not a judicial proceeding, so Judge Thayer's comments outside the courtroom could be used to demonstrate his bias. Once Thayer told reporters that "No long-haired anarchist from California can run this court!" According to the affidavits of eyewitnesses, Thayer also lectured members of his clubs, calling Sacco and Vanzetti "Bolsheviki!" and saying he would "get them good and proper". During the Dedham trial's first week, Thayer said to reporters: "Did you ever see a case in which so many leaflets and circulars have been spread ... saying people couldn't get a fair trial in Massachusetts? You wait till I give my charge to the jury, I'll show them!" In 1924, Thayer confronted a Massachusetts lawyer at Dartmouth, his alma mater, and said: "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day. I guess that will hold them for a while. ... Let them go to the Supreme Court now and see what they can get out of them." The Committee knew that, following the verdict, Boston Globe reporter Frank Sibley, who had covered the trial, wrote a protest to the Massachusetts attorney general condemning Thayer's blatant bias. Thayer's behavior both inside the courtroom and outside of it had become a public issue, with the New York World attacking Thayer as "an agitated little man looking for publicity and utterly impervious to the ethical standards one has the right to expect of a man presiding in a capital case."

On July 12–13, 1927, following testimony by the defense firearms expert Albert H. Hamilton before the Committee, the Assistant District Attorney for Massachusetts, Dudley P. Ranney, took the opportunity to cross-examine Hamilton. He submitted affidavits questioning Hamilton's credentials as well as his performance during the New York trial of Charles Stielow, in which Hamilton's testimony linking rifling marks to a bullet used to kill the victim nearly sent an innocent man to the electric chair. The Committee also heard from Braintree's police chief who told them he had found the cap on Pearl Street, allegedly dropped by Sacco during the crime, a full 24-hours after the getaway car had fled the scene. The chief doubted the cap belonged to Sacco and called the whole trial a contest "to see who could tell the biggest lies."

After two weeks of hearing witnesses and reviewing evidence, the Committee determined that the trial had been fair and a new trial was not warranted. They assessed the charges against Thayer as well. Their criticism, using words provided by Judge Grant, was direct: "He ought not to have talked about the case off the bench, and doing so was a grave breach of judicial decorum." But they also found some of the charges about his statements unbelievable or exaggerated, and they determined that anything he might have said had no impact on the trial. The panel's reading of the trial transcript convinced them that Thayer "tried to be scrupulously fair." The Committee also reported that the trial jurors were almost unanimous in praising Thayer's conduct of the trial.

A defense attorney later noted ruefully that the release of the Committee's report "abruptly stilled the burgeoning doubts among the leaders of opinion in New England." Supporters of the convicted men denounced the Committee. Harold Laski told Holmes that the Committee's work showed that Lowell's "loyalty to his class ... transcended his ideas of logic and justice."

Execution and funeral

The executions were scheduled for midnight between August 22 and 23, 1927. On August 15, a bomb exploded at the home of one of the Dedham jurors. On Sunday, August 21, more than 20,000 protesters assembled on Boston Common.

Sacco and Vanzetti awaited execution in their cells at Charlestown State Prison, and both men refused a priest several times on their last day, because they were militant atheists. Their attorney William Thompson asked Vanzetti to make a statement opposing violent retaliation for his death and they discussed forgiving one's enemies. Thompson also asked Vanzetti to swear to his and Sacco's innocence one last time, and Vanzetti did. Celestino Madeiros, whose execution had been delayed in case his testimony was required at another trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, was executed first. Sacco was next and walked quietly to the electric chair, then shouted "Farewell, mother." Vanzetti, in his final moments, shook hands with guards and thanked them for their kind treatment, read a statement proclaiming his innocence, and finally said, "I wish to forgive some people for what they are now doing to me." All three executions were carried out by Robert G. Elliott, the state executioner. Following the executions, death masks were made of the men.

Violent demonstrations swept through many cities the next day, including Geneva, London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Tokyo. In South America wildcat strikes closed factories. Three died in Germany, and protesters in Johannesburg burned an American flag outside the American embassy. It has been alleged that some of these activities were organized by the Communist Party.

At Langone Funeral Home in Boston's North End, more than 10,000 mourners viewed Sacco and Vanzetti in open caskets over two days. At the funeral parlor, a wreath over the caskets announced In attesa l'ora della vendetta (Awaiting the hour of vengeance). On Sunday, August 28, a two-hour funeral procession bearing huge floral tributes moved through the city. Thousands of marchers took part in the procession, and over 200,000 came out to watch. Police blocked the route, which passed the State House, and at one point mourners and the police clashed. The hearses reached Forest Hills Cemetery where, after a brief eulogy, the bodies were cremated. The Boston Globe called it "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times." Will H. Hays, head of the motion picture industry's umbrella organization, ordered all film of the funeral procession destroyed.

Sacco's ashes were sent to Torremaggiore, the town of his birth, where they are interred at the base of a monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother in Villafalletto.

<snip>

Later evidence and investigations

In 1941, anarchist leader Carlo Tresca, a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee, told Max Eastman, "Sacco was guilty but Vanzetti was innocent", although it is clear from his statement that Tresca equated guilt only with the act of pulling the trigger, i.e., Vanzetti was not the principal triggerman in Tresca's view, but was an accomplice to Sacco. This conception of innocence is in sharp contrast to the legal one. Both The Nation and The New Republic refused to publish Tresca's revelation, which Eastman said occurred after he pressed Tresca for the truth about the two men's involvement in the shooting. The story finally appeared in National Review in October 1961. Others who had known Tresca confirmed that he had made similar statements to them,[189] but Tresca's daughter insisted her father never hinted at Sacco's guilt. Others attributed Tresca's revelations to his disagreements with the Galleanists.

Labor organizer Anthony Ramuglia, an anarchist in the 1920s, said in 1952 that a Boston anarchist group had asked him to be a false alibi witness for Sacco. After agreeing, he had remembered that he had been in jail on the day in question, so he could not testify.

Both Sacco and Vanzetti had previously fled to Mexico, changing their names in order to evade draft registration, a fact the prosecutor in their murder trial used to demonstrate their lack of patriotism and which they were not allowed to rebut. Sacco and Vanzetti's supporters would later argue that the men fled the country to avoid persecution and conscription; their critics said they left to escape detection and arrest for militant and seditious activities in the United States. However, a 1953 Italian history of anarchism written by anonymous colleagues revealed a different motivation:

Several dozen Italian anarchists left the United States for Mexico. Some have suggested they did so because of cowardice. Nothing could be more false. The idea to go to Mexico arose in the minds of several comrades who were alarmed by the idea that, remaining in the United States, they would be forcibly restrained from leaving for Europe, where the revolution that had burst out in Russia that February promised to spread all over the continent.

In October 1961, ballistic tests were run with improved technology on Sacco's Colt semi-automatic pistol. The results confirmed that the bullet that killed Berardelli in 1920 was fired from Sacco's pistol. The Thayer court's habit of mistakenly referring to Sacco's .32 Colt pistol as well as any other automatic pistol as a "revolver" (a popular custom of the day) has sometimes mystified later-generation researchers attempting to follow the forensic evidence trail.

In 1987, Charlie Whipple, a former Boston Globe editorial page editor, revealed a conversation that he had with Sergeant Edward J. Seibolt in 1937. According to Whipple, Seibolt said that "we switched the murder weapon in that case", but indicated that he would deny this if Whipple ever printed it. However, at the time of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, Seibolt was only a patrolman, and did not work in the Boston Police ballistics department; Seibolt died in 1961 without corroborating Whipple's story. In 1935, Captain Charles Van Amburgh, a key ballistics witness for the prosecution, wrote a six-part article on the case for a pulp detective magazine. Van Amburgh described a scene in which Thayer caught defense ballistics expert Hamilton trying to leave the courtroom with Sacco's gun. However, Thayer said nothing about such a move during the hearing on the gun barrel switch and refused to blame either side. Following the private hearing on the gun barrel switch, Van Amburgh kept Sacco's gun in his house, where it remained until the Boston Globe did an exposé in 1960.

In 1973, a former mobster published a confession by Frank "Butsy" Morelli, Joe's brother. "We whacked them out, we killed those guys in the robbery," Butsy Morelli told Vincent Teresa. "These two greaseballs Sacco and Vanzetti took it on the chin."

Before his death in June 1982, Giovanni Gambera, a member of the four-person team of anarchist leaders who met shortly after the arrest of Sacco and Vanzetti to plan their defense, told his son that "everyone [in the anarchist inner circle] knew that Sacco was guilty and that Vanzetti was innocent as far as the actual participation in killing."

Months before he died, the distinguished jurist Charles E. Wyzanski, Jr., who had presided for 45 years on the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, wrote to Russell stating, "I myself am persuaded by your writings that Sacco was guilty." The judge's assessment was significant, because he was one of Felix Frankfurter's "Hot Dogs," and Justice Frankfurter had advocated his appointment to the federal bench.

The Los Angeles Times published an article on December 24, 2005, "Sinclair Letter Turns Out to Be Another Expose", which references a newly discovered letter from Upton Sinclair to attorney John Beardsley in which Sinclair, a socialist writer famous for his muckraking novels, revealed a conversation with Fred Moore, attorney for Sacco and Vanzetti. In that conversation, in response to Sinclair's request for the truth, Moore stated that both Sacco and Vanzetti were in fact guilty, and that Moore had fabricated their alibis in an attempt to avoid a guilty verdict. The Los Angeles Times interprets subsequent letters as indicating that, to avoid loss of sales to his radical readership, particularly abroad, and due to fears for his own safety, Sinclair didn't change the premise of his novel in that respect. However, Sinclair also expressed in the letters in question doubts as to whether Moore deserved to be trusted in the first place, and he did not actually assert the innocence of the two in the novel, focusing instead on the argument that the trial they got was not fair.

Dukakis proclamation

In 1977, as the 50th anniversary of the executions approached, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis asked the Office of the Governor's Legal Counsel to report on "whether there are substantial grounds for believing–at least in the light of the legal standards of today–that Sacco and Vanzetti were unfairly convicted and executed" and to recommend appropriate action. The resulting "Report to the Governor in the Matter of Sacco and Vanzetti" detailed grounds for doubting that the trial was conducted fairly in the first instance, and argued as well that such doubts were only reinforced by "later-discovered or later-disclosed evidence." The Report questioned prejudicial cross-examination that the trial judge allowed, the judge's hostility, the fragmentary nature of the evidence, and eyewitness testimony that came to light after the trial. It found the judge's charge to the jury troubling for the way it emphasized the defendants' behavior at the time of their arrest and highlighted certain physical evidence that was later called into question. The Report also dismissed the argument that the trial had been subject to judicial review, noting that "the system for reviewing murder cases at the time ... failed to provide the safeguards now present."

Based on recommendations of the Office of Legal Counsel, Dukakis declared August 23, 1977, the 50th anniversary of their execution, as Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. His proclamation, issued in English and Italian, stated that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names." He did not pardon them, because that would imply they were guilty. Neither did he assert their innocence. A resolution to censure Dukakis failed in the Massachusetts Senate by a vote of 23 to 12. Dukakis later expressed regret only for not reaching out to the families of the victims of the crime.

</snip>

Controversial anarchist trial defendants Bartolomeo Vanzetti (left) and Nicola Sacco

Nicola Sacco (April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian-born American anarchists who were controversially convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during the April 15, 1920 armed robbery of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts, United States. Seven years later, they were electrocuted in the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison. Both men adhered to an anarchist movement.

After a few hours' deliberation on July 14, 1921, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of first-degree murder and they were sentenced to death by the trial judge. Anti-Italianism, anti-immigrant bias, and anti-right political motives were suspected as having heavily influenced the verdict. A series of appeals followed, funded largely by the private Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee. The appeals were based on recanted testimony, conflicting ballistics evidence, a prejudicial pre-trial statement by the jury foreman, and a confession by an alleged participant in the robbery. All appeals were denied by trial judge Webster Thayer and also later denied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. By 1926, the case had drawn worldwide attention. As details of the trial and the men's suspected innocence became known, Sacco and Vanzetti became the center of one of the largest causes célèbres in modern history. In 1927, protests on their behalf were held in every major city in North America and Europe, as well as in Tokyo, Sydney, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, and Auckland.

Celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their pardon or for a new trial. Harvard law professor and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter argued for their innocence in a widely read Atlantic Monthly article that was later published in book form. The two were scheduled to die in April 1927, accelerating the outcry. Responding to a massive influx of telegrams urging their pardon, Massachusetts governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-man commission to investigate the case. After weeks of secret deliberation that included interviews with the judge, lawyers, and several witnesses, the commission upheld the verdict. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair just after midnight on August 23, 1927. Subsequent riots destroyed property in Paris, London, and other cities.

Investigations in the aftermath of the executions continued throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The publication of the men's letters, containing eloquent professions of innocence, intensified belief in their wrongful execution. Additional ballistics tests and incriminating statements by the men's acquaintances have clouded the case. On August 23, 1977—the 50th anniversary of the executions—Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names".

<snip>

Robbery

The Slater-Morrill Shoe Company factory was located on Pearl Street in Braintree, Massachusetts. On April 15, 1920, two men were robbed and killed while transporting the company's payroll in two large steel boxes to the main factory. One of them, Alessandro Berardelli —a security guard— was shot four times as he reached for his hip-holstered .38-caliber, Harrington & Richardson revolver; his gun was not recovered from the scene. The other man, Frederick Parmenter—a paymaster who was unarmed—was shot twice: once in the chest and a second time, fatally, in the back as he attempted to flee. The robbers seized the payroll boxes and escaped in a stolen dark blue Buick that sped up and was carrying several other men.

As the car was being driven away, the robbers fired wildly at company workers nearby. A coroner's report and subsequent ballistic investigation revealed that six bullets removed from the murdered men's bodies were of .32 automatic (ACP) caliber. Five of these .32-caliber bullets were all fired from a single semi-automatic pistol, a .32-caliber Savage Model 1907, which used a particularly narrow-grooved barrel rifling with a right-hand twist. Two of the bullets were recovered from Berardelli's body. Four .32 automatic brass shell casings were found at the murder scene, manufactured by one of three firms: Peters, Winchester, or Remington. The Winchester cartridge case was of a relatively obsolete cartridge loading, which had been discontinued from production some years earlier. Two days after the robbery, police located the robbers' Buick; several 12-gauge shotgun shells were found on the ground nearby.

Arrests and indictment

An earlier attempted robbery of another shoe factory occurred on December 24, 1919 in Bridgewater, Massachusetts by people identified as Italian who used a car that was seen escaping to Cochesett in West Bridgewater. Police speculated that Italian anarchists perpetrated the robberies to finance their activities. Bridgewater police chief Michael E. Stewart suspected that known Italian anarchist Ferruccio Coacci was involved. Stewart discovered that Mario Buda (aka 'Mike' Boda) lived with Coacci.

On April 16—one day after the Braintree robbery-murders—the Federal Immigration Service (FIS) called Chief Stewart to discuss Galleanist and anarchist Coacci, whom Stewart had arrested on their behalf two years earlier. Coacci was slated for deportation on April 15, 1920, the day of the Braintree holdup, but telephoned with the excuse that his wife was ill. The FIS asked Stewart to investigate Coacci's excuse for failing to report for deportation on April 15. On April 16, officers discovered Coacci at home and determined that he had given a false alibi for not showing up for deportation. They offered him another week, but Coacci declined and left for Italy on April 18, 1920.

When Chief Stewart later arrived at the Coacci home, Coacci was missing but they found Buda. When he was questioned, Buda said that Coacci owned a .32 Savage automatic pistol, which he kept in the kitchen. A search of the kitchen did not locate the gun, but Stewart found a manufacturer's technical diagram for a Model 1907 .32 Savage automatic pistol – the exact pistol type and caliber used to shoot Parmenter and Berardelli – in a kitchen drawer. Stewart asked Buda if he owned a gun, and the man produced a .32-caliber Spanish-made automatic pistol. Buda told police that he owned a 1914 Overland automobile, which was being repaired. The car was delivered for repairs four days after the Braintree crimes, but it was old and apparently had not been run for five months. Tire tracks were seen near the abandoned Buick getaway car, and Chief Stewart surmised that two cars had been used in the getaway, and that Buda's car might have been the second car. The garage proprietor who was repairing Buda's vehicle was instructed to call the police if anyone came to pick up the car.

When Stewart discovered that Coacci had worked for both shoe factories that had been robbed, he returned with the Bridgewater police. Coacci had since left for Italy with his family along with his possessions, and Buda had just escaped.

On May 5, 1920, Mario Buda arrived at the garage with three other men, later identified as Sacco, Vanzetti, and Riccardo Orciani. The four men knew each other well; Buda would later call Sacco and Vanzetti "the best friends I had in America." Police were alerted, but the men left. Buda escaped and did not resurface until 1928 in Italy.

Sacco and Vanzetti boarded a streetcar, but were tracked down and soon arrested. When searched by police, both denied owning any guns, but were found to be holding loaded pistols. Sacco was found to have an Italian passport, anarchist literature, a loaded .32 Colt Model 1903 automatic pistol, and twenty-three .32 Automatic cartridges in his possession; several of those bullet cases were of the same obsolescent type as the empty Winchester .32 casing found at the crime scene, and others were manufactured by the firms of Peters and Remington, much like other casings found at the scene. Vanzetti had four 12-gauge shotgun shells and a five-shot nickel-plated .38-caliber Harrington & Richardson revolver similar to the .38 carried by Berardelli, the slain Braintree guard, whose weapon was not found at the scene of the crime. When they were questioned, the pair denied any connection to anarchists.

Orciani was arrested May 6, but gave the alibi that he had been at work on the day of both crimes. Sacco had been at work on the day of the Bridgewater crimes but said that he had the day off on April 15—the day of the Braintree crimes— and was charged with those murders. The self-employed Vanzetti had no such alibis and was charged for the attempted robbery and attempted murder in Bridgewater and the robbery and murder in the Braintree crimes. Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime of murder on May 5, 1920 and indicted four months later on September 14.

Following Sacco and Vanzetti's indictment for murder for the Braintree robbery, Galleanists and anarchists in the United States and abroad began a campaign of violent retaliation. Two days later on September 16, 1920, Mario Buda allegedly orchestrated the Wall Street bombing, where a time-delay dynamite bomb packed with heavy iron sash-weights in a horse-drawn cart exploded, killing 38 people and wounding 134. In 1921, a booby trap bomb mailed to the American ambassador in Paris exploded, wounding his valet. For the next six years, bombs exploded at other American embassies all over the world.

<snip>

Sentencing

On April 9, 1927, Judge Thayer heard final statements from Sacco and Vanzetti. In a lengthy speech Vanzetti said:

I would not wish to a dog or to a snake, to the most low and misfortunate creature of the earth, I would not wish to any of them what I have had to suffer for things that I am not guilty of. But my conviction is that I have suffered for things that I am guilty of. I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I am an Italian and indeed I am an Italian ... if you could execute me two times, and if I could be reborn two other times, I would live again to do what I have done already.

Thayer declared that the responsibility for the conviction rested solely with the jury's determination of guilt. "The Court has absolutely nothing to do with that question." He sentenced each of them to "suffer the punishment of death by the passage of a current of electricity through your body" during the week beginning July 10. He twice postponed the execution date while the governor considered requests for clemency.[130]

On May 10, a package bomb addressed to Governor Fuller was intercepted in the Boston post office.

Clemency appeal and the Governor's Advisory Committee

In response to public protests that greeted the sentencing, Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller faced last-minute appeals to grant clemency to Sacco and Vanzetti. On June 1, 1927, he appointed an Advisory Committee of three: President Abbott Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, President Samuel Wesley Stratton of MIT, and Probate Judge Robert Grant. They were presented with the task of reviewing the trial to determine whether it had been fair. Lowell's appointment was generally well received, for though he had controversy in his past, he had also at times demonstrated an independent streak. The defense attorneys considered resigning when they determined that the Committee was biased against the defendants, but some of the defendants' most prominent supporters, including Harvard Law Professor Felix Frankfurter and Judge Julian W. Mack of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, persuaded them to stay because Lowell "was not entirely hopeless."

One of the defense attorneys, though ultimately very critical of the Committee's work, thought the Committee members were not really capable of the task the Governor set for them:

No member of the Committee had the essential sophistication that comes with experience in the trial of criminal cases. ... The high positions in the community held by the members of the Committee obscured the fact that they were not really qualified to perform the difficult task assigned to them.

He also thought that the Committee, particularly Lowell, imagined it could use its fresh and more powerful analytical abilities to outperform the efforts of those who had worked on the case for years, even finding evidence of guilt that professional prosecutors had discarded.

Grant was another establishment figure, a probate court judge from 1893 to 1923 and an Overseer of Harvard University from 1896 to 1921, and the author of a dozen popular novels. Some criticized Grant's appointment to the Committee, with one defense lawyer saying he "had a black-tie class concept of life around him," but Harold Laski in a conversation at the time found him "moderate." Others cited evidence of xenophobia in some of his novels, references to "riff-raff" and a variety of racial slurs. His biographer allows that he was "not a good choice," not a legal scholar, and handicapped by age. Stratton, the one member who was not a "Boston Brahmin," maintained the lowest public profile of the three and hardly spoke during its hearings.

In their earlier appeals, the defense was limited to the trial record. The Governor's Committee, however, was not a judicial proceeding, so Judge Thayer's comments outside the courtroom could be used to demonstrate his bias. Once Thayer told reporters that "No long-haired anarchist from California can run this court!" According to the affidavits of eyewitnesses, Thayer also lectured members of his clubs, calling Sacco and Vanzetti "Bolsheviki!" and saying he would "get them good and proper". During the Dedham trial's first week, Thayer said to reporters: "Did you ever see a case in which so many leaflets and circulars have been spread ... saying people couldn't get a fair trial in Massachusetts? You wait till I give my charge to the jury, I'll show them!" In 1924, Thayer confronted a Massachusetts lawyer at Dartmouth, his alma mater, and said: "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day. I guess that will hold them for a while. ... Let them go to the Supreme Court now and see what they can get out of them." The Committee knew that, following the verdict, Boston Globe reporter Frank Sibley, who had covered the trial, wrote a protest to the Massachusetts attorney general condemning Thayer's blatant bias. Thayer's behavior both inside the courtroom and outside of it had become a public issue, with the New York World attacking Thayer as "an agitated little man looking for publicity and utterly impervious to the ethical standards one has the right to expect of a man presiding in a capital case."

On July 12–13, 1927, following testimony by the defense firearms expert Albert H. Hamilton before the Committee, the Assistant District Attorney for Massachusetts, Dudley P. Ranney, took the opportunity to cross-examine Hamilton. He submitted affidavits questioning Hamilton's credentials as well as his performance during the New York trial of Charles Stielow, in which Hamilton's testimony linking rifling marks to a bullet used to kill the victim nearly sent an innocent man to the electric chair. The Committee also heard from Braintree's police chief who told them he had found the cap on Pearl Street, allegedly dropped by Sacco during the crime, a full 24-hours after the getaway car had fled the scene. The chief doubted the cap belonged to Sacco and called the whole trial a contest "to see who could tell the biggest lies."

After two weeks of hearing witnesses and reviewing evidence, the Committee determined that the trial had been fair and a new trial was not warranted. They assessed the charges against Thayer as well. Their criticism, using words provided by Judge Grant, was direct: "He ought not to have talked about the case off the bench, and doing so was a grave breach of judicial decorum." But they also found some of the charges about his statements unbelievable or exaggerated, and they determined that anything he might have said had no impact on the trial. The panel's reading of the trial transcript convinced them that Thayer "tried to be scrupulously fair." The Committee also reported that the trial jurors were almost unanimous in praising Thayer's conduct of the trial.

A defense attorney later noted ruefully that the release of the Committee's report "abruptly stilled the burgeoning doubts among the leaders of opinion in New England." Supporters of the convicted men denounced the Committee. Harold Laski told Holmes that the Committee's work showed that Lowell's "loyalty to his class ... transcended his ideas of logic and justice."

Execution and funeral

The executions were scheduled for midnight between August 22 and 23, 1927. On August 15, a bomb exploded at the home of one of the Dedham jurors. On Sunday, August 21, more than 20,000 protesters assembled on Boston Common.

Sacco and Vanzetti awaited execution in their cells at Charlestown State Prison, and both men refused a priest several times on their last day, because they were militant atheists. Their attorney William Thompson asked Vanzetti to make a statement opposing violent retaliation for his death and they discussed forgiving one's enemies. Thompson also asked Vanzetti to swear to his and Sacco's innocence one last time, and Vanzetti did. Celestino Madeiros, whose execution had been delayed in case his testimony was required at another trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, was executed first. Sacco was next and walked quietly to the electric chair, then shouted "Farewell, mother." Vanzetti, in his final moments, shook hands with guards and thanked them for their kind treatment, read a statement proclaiming his innocence, and finally said, "I wish to forgive some people for what they are now doing to me." All three executions were carried out by Robert G. Elliott, the state executioner. Following the executions, death masks were made of the men.

Violent demonstrations swept through many cities the next day, including Geneva, London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Tokyo. In South America wildcat strikes closed factories. Three died in Germany, and protesters in Johannesburg burned an American flag outside the American embassy. It has been alleged that some of these activities were organized by the Communist Party.

At Langone Funeral Home in Boston's North End, more than 10,000 mourners viewed Sacco and Vanzetti in open caskets over two days. At the funeral parlor, a wreath over the caskets announced In attesa l'ora della vendetta (Awaiting the hour of vengeance). On Sunday, August 28, a two-hour funeral procession bearing huge floral tributes moved through the city. Thousands of marchers took part in the procession, and over 200,000 came out to watch. Police blocked the route, which passed the State House, and at one point mourners and the police clashed. The hearses reached Forest Hills Cemetery where, after a brief eulogy, the bodies were cremated. The Boston Globe called it "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times." Will H. Hays, head of the motion picture industry's umbrella organization, ordered all film of the funeral procession destroyed.

Sacco's ashes were sent to Torremaggiore, the town of his birth, where they are interred at the base of a monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother in Villafalletto.

<snip>

Later evidence and investigations

In 1941, anarchist leader Carlo Tresca, a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee, told Max Eastman, "Sacco was guilty but Vanzetti was innocent", although it is clear from his statement that Tresca equated guilt only with the act of pulling the trigger, i.e., Vanzetti was not the principal triggerman in Tresca's view, but was an accomplice to Sacco. This conception of innocence is in sharp contrast to the legal one. Both The Nation and The New Republic refused to publish Tresca's revelation, which Eastman said occurred after he pressed Tresca for the truth about the two men's involvement in the shooting. The story finally appeared in National Review in October 1961. Others who had known Tresca confirmed that he had made similar statements to them,[189] but Tresca's daughter insisted her father never hinted at Sacco's guilt. Others attributed Tresca's revelations to his disagreements with the Galleanists.

Labor organizer Anthony Ramuglia, an anarchist in the 1920s, said in 1952 that a Boston anarchist group had asked him to be a false alibi witness for Sacco. After agreeing, he had remembered that he had been in jail on the day in question, so he could not testify.

Both Sacco and Vanzetti had previously fled to Mexico, changing their names in order to evade draft registration, a fact the prosecutor in their murder trial used to demonstrate their lack of patriotism and which they were not allowed to rebut. Sacco and Vanzetti's supporters would later argue that the men fled the country to avoid persecution and conscription; their critics said they left to escape detection and arrest for militant and seditious activities in the United States. However, a 1953 Italian history of anarchism written by anonymous colleagues revealed a different motivation:

Several dozen Italian anarchists left the United States for Mexico. Some have suggested they did so because of cowardice. Nothing could be more false. The idea to go to Mexico arose in the minds of several comrades who were alarmed by the idea that, remaining in the United States, they would be forcibly restrained from leaving for Europe, where the revolution that had burst out in Russia that February promised to spread all over the continent.

In October 1961, ballistic tests were run with improved technology on Sacco's Colt semi-automatic pistol. The results confirmed that the bullet that killed Berardelli in 1920 was fired from Sacco's pistol. The Thayer court's habit of mistakenly referring to Sacco's .32 Colt pistol as well as any other automatic pistol as a "revolver" (a popular custom of the day) has sometimes mystified later-generation researchers attempting to follow the forensic evidence trail.

In 1987, Charlie Whipple, a former Boston Globe editorial page editor, revealed a conversation that he had with Sergeant Edward J. Seibolt in 1937. According to Whipple, Seibolt said that "we switched the murder weapon in that case", but indicated that he would deny this if Whipple ever printed it. However, at the time of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, Seibolt was only a patrolman, and did not work in the Boston Police ballistics department; Seibolt died in 1961 without corroborating Whipple's story. In 1935, Captain Charles Van Amburgh, a key ballistics witness for the prosecution, wrote a six-part article on the case for a pulp detective magazine. Van Amburgh described a scene in which Thayer caught defense ballistics expert Hamilton trying to leave the courtroom with Sacco's gun. However, Thayer said nothing about such a move during the hearing on the gun barrel switch and refused to blame either side. Following the private hearing on the gun barrel switch, Van Amburgh kept Sacco's gun in his house, where it remained until the Boston Globe did an exposé in 1960.

In 1973, a former mobster published a confession by Frank "Butsy" Morelli, Joe's brother. "We whacked them out, we killed those guys in the robbery," Butsy Morelli told Vincent Teresa. "These two greaseballs Sacco and Vanzetti took it on the chin."

Before his death in June 1982, Giovanni Gambera, a member of the four-person team of anarchist leaders who met shortly after the arrest of Sacco and Vanzetti to plan their defense, told his son that "everyone [in the anarchist inner circle] knew that Sacco was guilty and that Vanzetti was innocent as far as the actual participation in killing."

Months before he died, the distinguished jurist Charles E. Wyzanski, Jr., who had presided for 45 years on the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, wrote to Russell stating, "I myself am persuaded by your writings that Sacco was guilty." The judge's assessment was significant, because he was one of Felix Frankfurter's "Hot Dogs," and Justice Frankfurter had advocated his appointment to the federal bench.

The Los Angeles Times published an article on December 24, 2005, "Sinclair Letter Turns Out to Be Another Expose", which references a newly discovered letter from Upton Sinclair to attorney John Beardsley in which Sinclair, a socialist writer famous for his muckraking novels, revealed a conversation with Fred Moore, attorney for Sacco and Vanzetti. In that conversation, in response to Sinclair's request for the truth, Moore stated that both Sacco and Vanzetti were in fact guilty, and that Moore had fabricated their alibis in an attempt to avoid a guilty verdict. The Los Angeles Times interprets subsequent letters as indicating that, to avoid loss of sales to his radical readership, particularly abroad, and due to fears for his own safety, Sinclair didn't change the premise of his novel in that respect. However, Sinclair also expressed in the letters in question doubts as to whether Moore deserved to be trusted in the first place, and he did not actually assert the innocence of the two in the novel, focusing instead on the argument that the trial they got was not fair.

Dukakis proclamation

In 1977, as the 50th anniversary of the executions approached, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis asked the Office of the Governor's Legal Counsel to report on "whether there are substantial grounds for believing–at least in the light of the legal standards of today–that Sacco and Vanzetti were unfairly convicted and executed" and to recommend appropriate action. The resulting "Report to the Governor in the Matter of Sacco and Vanzetti" detailed grounds for doubting that the trial was conducted fairly in the first instance, and argued as well that such doubts were only reinforced by "later-discovered or later-disclosed evidence." The Report questioned prejudicial cross-examination that the trial judge allowed, the judge's hostility, the fragmentary nature of the evidence, and eyewitness testimony that came to light after the trial. It found the judge's charge to the jury troubling for the way it emphasized the defendants' behavior at the time of their arrest and highlighted certain physical evidence that was later called into question. The Report also dismissed the argument that the trial had been subject to judicial review, noting that "the system for reviewing murder cases at the time ... failed to provide the safeguards now present."

Based on recommendations of the Office of Legal Counsel, Dukakis declared August 23, 1977, the 50th anniversary of their execution, as Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. His proclamation, issued in English and Italian, stated that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names." He did not pardon them, because that would imply they were guilty. Neither did he assert their innocence. A resolution to censure Dukakis failed in the Massachusetts Senate by a vote of 23 to 12. Dukakis later expressed regret only for not reaching out to the families of the victims of the crime.

</snip>

April 14, 2019

A terrible event in the middle of the misery of the Great Depression...

84 Years Ago Today; The Black Sunday Dust Storm

Black Sunday (storm)

The "Black Sunday" dust storm approaches Spearman in northern Texas, April 14, 1935.

Black Sunday refers to a particularly severe dust storm that occurred on April 14, 1935, as part of the Dust Bowl. It was one of the worst dust storms in American history and it caused immense economic and agricultural damage. It is estimated to have displaced 300 million tons of topsoil from the prairie area in the US.

On the afternoon of April 14, the residents of the Plains States were forced to take cover as a dust storm, or "black blizzard", blew through the region. The storm hit the Oklahoma Panhandle and Northwestern Oklahoma first, and moved south for the remainder of the day. It hit Beaver around 4:00 p.m., Boise City around 5:15 p.m., and Amarillo, Texas, at 7:20 p.m. The conditions were the most severe in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles, but the storm's effects were felt in other surrounding areas.

The storm was harsh due to the high winds that hit the area that day. The combination of drought, erosion, bare soil, and winds caused the dust to fly freely and at high speeds.

The Dust Bowl

In North America, the term "Dust Bowl" was first used to describe a series of dust storms that hit the prairies of Canada and the United States during the 1930s, and later to describe the area in the United States that was most affected by the storms, including western Kansas, eastern Colorado, northeastern New Mexico, and the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles.

The "black blizzards" started in the Eastern states in 1930, affecting agriculture from Maine to Arkansas. By 1934 they had reached the Great Plains, stretching from North Dakota to Texas, and from the Mississippi River Valley to the Rocky Mountains. "The Dust Bowl" (as an area) received its name following the disastrous "Black Sunday" storm in April 1935, when reporter Robert E. Geiger referred to the region as "The Dust Bowl" in his account of the storm.

Causes

Cattle farming and sheep ranching had left much of the West devoid of natural grass and shrubs to anchor the soil, and over-farming and poor soil stewardship left the soil dehydrated and lacking in organic matter. During a massive drought that hit the United States in the 1930s, the lack of rainfall, snowfall, and moisture in the air dried out the top soil in most of the country's farming regions.

Effects

The destruction caused by the dust storms, and especially by the storm on Black Sunday, killed multiple people[citation needed] and caused hundreds of thousands of people to relocate. Poor migrants from the American Southwest (known as "Okies" - though only about 20 percent were from Oklahoma) flooded California, overtaxing the state's health and employment infrastructure.

In 1935, after the massive damage caused by these storms, Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act, which established the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) as a permanent agency of the USDA. The SCS was created in an attempt to provide guidance for land owners and land users to reduce soil erosion, improve forest and field land and conserve and develop natural resources.

Personal accounts of Black Sunday and other dust storms

During the 1930s, many residents of the Dust Bowl kept accounts and journals of their lives and of the storms that hit their areas. Collections of accounts of the dust storms during the 1930s have been compiled over the years and are now available in book collections and online.

Lawrence Svobida was a wheat farmer in Kansas during the 1930s. He experienced the period of dust storms, and the effect that they had on the surrounding environment and the society. His observations and feelings are available in his memoirs, Farming the Dust Bowl. Here he describes an approaching dust storm:

The Black Sunday storm is detailed in the 2012 Ken Burns PBS documentary The Dust Bowl.

Media references

Musicians and songwriters began to reflect the Dust Bowl and the events of the 1930s in their music. Woody Guthrie, a singer-songwriter from Oklahoma, wrote a variety of songs documenting his experiences living during the era of dust storms. Several were collected in his first album Dust Bowl Ballads. One of them, Great Dust Storm, describes the events of Black Sunday. An excerpt of the lyrics follows:

Musician Kat Eggleston has written a play, The Cyclone Line, about her father Al Eggleston's experiences growing up in 1930s Oklahoma, Black Sunday, and the Dust Bowl in general. Its first public performances were on Vashon (Island), Washington, where he lived most of his life.

Americana recording artist Grant Maloy Smith released an album in 2017 called Dust Bowl – American Stories that featured two songs that directly referenced Black Sunday. The song "Old Black Roller" is written from a first person perspective during the Black Sunday storm, and another song "Never Seen The Rain" has these chorus lyrics: "We worked the land to death, me and my brother | 'Til April 14, 1935 | Oklahoma, you were like our mother - oh, my"

American recording artist Gillian Welch refers to the storm and other historical events in a two-part song on her 2001 album Time (The Revelator) : "April the 14th Part I" and "Ruination Day Part II".

</snip>

The "Black Sunday" dust storm approaches Spearman in northern Texas, April 14, 1935.

Black Sunday refers to a particularly severe dust storm that occurred on April 14, 1935, as part of the Dust Bowl. It was one of the worst dust storms in American history and it caused immense economic and agricultural damage. It is estimated to have displaced 300 million tons of topsoil from the prairie area in the US.

On the afternoon of April 14, the residents of the Plains States were forced to take cover as a dust storm, or "black blizzard", blew through the region. The storm hit the Oklahoma Panhandle and Northwestern Oklahoma first, and moved south for the remainder of the day. It hit Beaver around 4:00 p.m., Boise City around 5:15 p.m., and Amarillo, Texas, at 7:20 p.m. The conditions were the most severe in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles, but the storm's effects were felt in other surrounding areas.

The storm was harsh due to the high winds that hit the area that day. The combination of drought, erosion, bare soil, and winds caused the dust to fly freely and at high speeds.

The Dust Bowl

In North America, the term "Dust Bowl" was first used to describe a series of dust storms that hit the prairies of Canada and the United States during the 1930s, and later to describe the area in the United States that was most affected by the storms, including western Kansas, eastern Colorado, northeastern New Mexico, and the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles.

The "black blizzards" started in the Eastern states in 1930, affecting agriculture from Maine to Arkansas. By 1934 they had reached the Great Plains, stretching from North Dakota to Texas, and from the Mississippi River Valley to the Rocky Mountains. "The Dust Bowl" (as an area) received its name following the disastrous "Black Sunday" storm in April 1935, when reporter Robert E. Geiger referred to the region as "The Dust Bowl" in his account of the storm.

Causes

Cattle farming and sheep ranching had left much of the West devoid of natural grass and shrubs to anchor the soil, and over-farming and poor soil stewardship left the soil dehydrated and lacking in organic matter. During a massive drought that hit the United States in the 1930s, the lack of rainfall, snowfall, and moisture in the air dried out the top soil in most of the country's farming regions.

Effects

The destruction caused by the dust storms, and especially by the storm on Black Sunday, killed multiple people[citation needed] and caused hundreds of thousands of people to relocate. Poor migrants from the American Southwest (known as "Okies" - though only about 20 percent were from Oklahoma) flooded California, overtaxing the state's health and employment infrastructure.

In 1935, after the massive damage caused by these storms, Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act, which established the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) as a permanent agency of the USDA. The SCS was created in an attempt to provide guidance for land owners and land users to reduce soil erosion, improve forest and field land and conserve and develop natural resources.

Personal accounts of Black Sunday and other dust storms

During the 1930s, many residents of the Dust Bowl kept accounts and journals of their lives and of the storms that hit their areas. Collections of accounts of the dust storms during the 1930s have been compiled over the years and are now available in book collections and online.

"People caught in their own yards grope for the doorstep. Cars come to a standstill, for no light in the world can penetrate that swirling murk…. The nightmare is deepest during the storms. But on the occasional bright day and the usual gray day we cannot shake from it. We live with the dust, eat it, sleep with it, watch it strip us of possessions and the hope of possessions."

—?Avis D. Carlson, The New Republic

Lawrence Svobida was a wheat farmer in Kansas during the 1930s. He experienced the period of dust storms, and the effect that they had on the surrounding environment and the society. His observations and feelings are available in his memoirs, Farming the Dust Bowl. Here he describes an approaching dust storm:

"… At other times a cloud is seen to be approaching from a distance of many miles. Already it has the banked appearance of a cumulus cloud, but it is black instead of white and it hangs low, seeming to hug the earth. Instead of being slow to change its form, it appears to be rolling on itself from the crest downward. As it sweeps onward, the landscape is progressively blotted out. Birds fly in terror before the storm, and only those that are strong of wing may escape. The smaller birds fly until they are exhausted, then fall to the ground, to share the fate of the thousands of jack rabbits which perish from suffocation."

The Black Sunday storm is detailed in the 2012 Ken Burns PBS documentary The Dust Bowl.

Media references

Musicians and songwriters began to reflect the Dust Bowl and the events of the 1930s in their music. Woody Guthrie, a singer-songwriter from Oklahoma, wrote a variety of songs documenting his experiences living during the era of dust storms. Several were collected in his first album Dust Bowl Ballads. One of them, Great Dust Storm, describes the events of Black Sunday. An excerpt of the lyrics follows:

On the 14th day of April of 1935,

There struck the worst of dust storms that ever filled the sky.

You could see that dust storm comin', the cloud looked deathlike black,

And through our mighty nation, it left a dreadful track.

From Oklahoma City to the Arizona line,

Dakota and Nebraska to the lazy Rio Grande,

It fell across our city like a curtain of black rolled down,

We thought it was our judgement, we thought it was our doom.

Musician Kat Eggleston has written a play, The Cyclone Line, about her father Al Eggleston's experiences growing up in 1930s Oklahoma, Black Sunday, and the Dust Bowl in general. Its first public performances were on Vashon (Island), Washington, where he lived most of his life.

Americana recording artist Grant Maloy Smith released an album in 2017 called Dust Bowl – American Stories that featured two songs that directly referenced Black Sunday. The song "Old Black Roller" is written from a first person perspective during the Black Sunday storm, and another song "Never Seen The Rain" has these chorus lyrics: "We worked the land to death, me and my brother | 'Til April 14, 1935 | Oklahoma, you were like our mother - oh, my"

American recording artist Gillian Welch refers to the storm and other historical events in a two-part song on her 2001 album Time (The Revelator) : "April the 14th Part I" and "Ruination Day Part II".

</snip>

A terrible event in the middle of the misery of the Great Depression...

April 14, 2019

154 Years Ago Today; "You sockdologizing old man-trap!"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assassination_of_Abraham_Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, while attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, Lincoln died the following day at 7:22 am, in the Petersen House opposite the theater. He was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, and Lincoln's funeral and burial marked an extended period of national mourning.

Occurring near the end of the American Civil War, the assassination was part of a larger conspiracy intended by Booth to revive the Confederate cause by eliminating the three most important officials of the United States government. Conspirators Lewis Powell and David Herold were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson. Beyond Lincoln's death the plot failed: Seward was only wounded and Johnson's would-be attacker lost his nerve. After a dramatic initial escape, Booth was killed at the climax of a 12-day manhunt. Powell, Herold, Atzerodt and Mary Surratt were later hanged for their roles in the conspiracy.

<snip>

Assassination of Lincoln

Lincoln's box

Ford's Theatre

Lincoln arrives at the theater

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris (daughter of New York Senator Ira Harris) accepted. At one point Mary Lincoln developed a headache and was inclined to stay home, but Lincoln told her he must attend because newspapers had announced that he would.[25]One of Lincoln's bodyguards, William H. Crook, advised him not to go, but Lincoln said he had promised his wife. Lincoln told Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, "I suppose it's time to go though I would rather stay" before assisting Mary into the carriage.

The presidential party arrived late and settled into their box (two adjoining boxes with a dividing partition removed). The play was interrupted and the orchestra played "Hail to the Chief" as the full house of some 1,700 rose in applause. Lincoln sat in a rocking chair that had been selected for him from among the Ford family's personal furnishings.

Booth's Philadelphia Deringer