Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal49 years Ago Today; Tin soldiers and Nixon's coming...

Mary Ann Vecchio gestures and screams as she kneels by the body of a student, Jeffrey Miller, lying face down on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio.

The Kent State shootings, also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre, were the shootings on May 4, 1970, of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, during a mass protest against the bombing of Cambodia by United States military forces. Twenty-eight guardsmen fired approximately 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced during a television address on April 30 of that year. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of 4 million students,[10] and the event further affected public opinion, at an already socially contentious time, over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.

<snip>

Timeline

Thursday, April 30

President Nixon announced that the "Cambodian Incursion" had been launched by United States combat forces.

Friday, May 1

At Kent State University, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 p.m., another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to "bring the war home". A group of history students buried a copy of the United States Constitution to symbolize that Nixon had killed it. A sign was put on a tree asking "Why is the ROTC building still standing?"

Trouble exploded in town around midnight, when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at police cars and breaking windows in downtown storefronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called the office of Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.

Saturday, May 2

City officials and downtown businesses received threats, and rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Several merchants reported that they were told that if they did not display anti-war slogans, their business would be burned down. Kent's police chief told the mayor that according to a reliable informant, the ROTC building, the local army recruiting station and post office had been targeted for destruction that night. There were rumors of students with caches of arms, plots to poison the local water supply with LSD, of students building underground tunnels for the purpose of blowing up the town's main store. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting, Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances. The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 p.m., but the guard did not arrive in town that evening until around 10 p.m. By this time, a large demonstration was under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) building was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended, and no one was injured in the fire. According to the report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest:

Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion weren't Kent State students. There is also evidence to suggest that the burning was planned beforehand: railroad flares, a machete, and ice picks are not customarily carried to peaceful rallies.

There were reports that some Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it. The National Guard made numerous arrests, mostly for curfew violations, and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.

Sunday, May 3

During a press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk, pounding which can be heard in the recording of his speech. He called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio.

We've seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we're going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We're not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They're worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we're up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.

During the day, some students came to downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, actions which were met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8 p.m., another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 p.m., the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and University President Robert White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.

Monday, May 4

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts, an estimated 2,000 people gathered on the university's Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus's iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard's line and chanted "Pigs off campus!" The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on their M1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of the Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about 10 minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 to 225 ft (46 to 69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot, which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of them knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. At one point the guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About 10 minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back into the Commons.

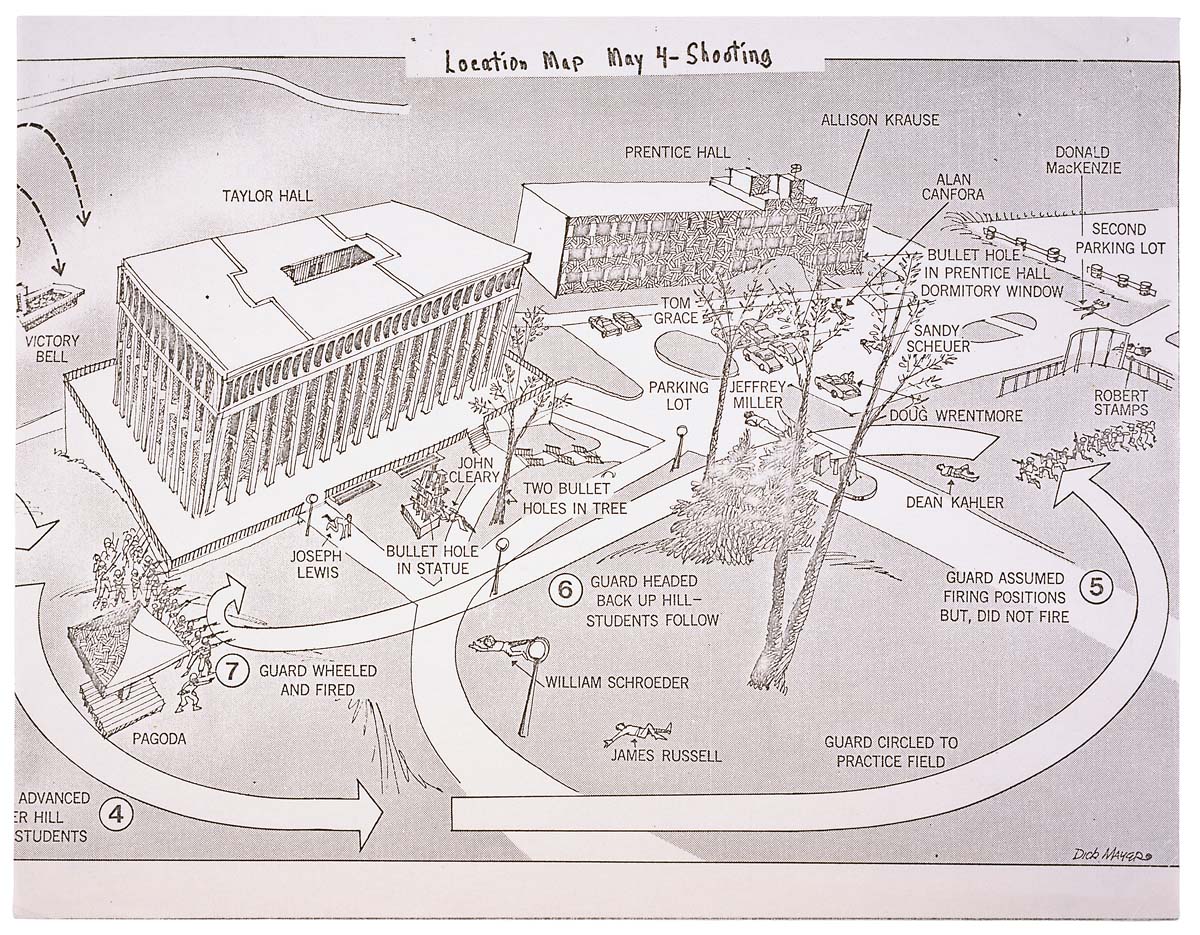

Map of the shootings

During their climb back to Blanket Hill, several guardsmen stopped and half-turned to keep their eyes on the students in the Prentice Hall parking lot. At 12:24 p.m., according to eyewitnesses, a sergeant named Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the crowd of students with his .45 pistol. A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their rifles at the students. In all, at least 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using an estimate of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in The New York Times that "it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer." The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

Photo taken from the perspective of where the Ohio National Guard soldiers stood when they opened fire on the students

Dent from a bullet in Solar Totem #1 sculpture by Don Drumm caused by a .30 caliber round fired by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970

The adjutant general of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that "triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State." The President's Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that "the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest. The other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 265 feet (81 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Eyewitness accounts

Several present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they're not going to shoot, they can't do that. If they are going to shoot, it's going to be blank.

Unidentified speaker 2:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit. He stumbled and fell, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

As this student fell behind the car, I saw another student go down, next to the curb, on the far side of the automobile, maybe 25 or 30 yards from where I was lying. It was maybe 25, 30, 35 seconds of sporadic firing.

The firing stopped. I lay there maybe 10 or 15 seconds. I got up, I saw four or five students lying around the lot. By this time, it was like mass hysteria. Students were crying, they were screaming for ambulances. I heard some girl screaming, "They didn't have blank, they didn't have blank," no, they didn't.

Another witness was Chrissie Hynde, the future lead singer of The Pretenders and a student at Kent State University at the time. In her 2015 autobiography she described what she saw:

Then I heard the tatatatatatatatatat sound. I thought it was fireworks. An eerie sound fell over the common. The quiet felt like gravity pulling us to the ground. Then a young man's voice: "They fucking killed somebody!" Everything slowed down and the silence got heavier.

The ROTC building, now nothing more than a few inches of charcoal, was surrounded by National Guardsmen. They were all on one knee and pointing their rifles at ... us! Then they fired.

By the time I made my way to where I could see them it was still unclear what was going on. The guardsmen themselves looked stunned. We looked at them and they looked at us. They were just kids, 19 years old, like us. But in uniform. Like our boys in Vietnam.

Gerald Casale, the future bassist/singer of Devo, also witnessed the shootings. While speaking to the Vermont Review in 2005, he recalled what he saw:

All I can tell you is that it completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew.

Two of the four people who were killed, Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause, were my friends. We were all running our asses off from these motherfuckers. It was total, utter bullshit. Live ammunition and gasmasks—none of us knew, none of us could have imagined ... They shot into a crowd that was running away from them!

I stopped being a hippie and I started to develop the idea of devolution. I got real, real pissed off.

Victims

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Jeffrey Glenn Miller; age 20; 265 ft (81 m) shot through the mouth; killed instantly

Allison B. Krause; age 19; 343 ft (105 m) fatal left chest wound; died later that day

William Knox Schroeder; age 19; 382 ft (116 m) fatal chest wound; died almost an hour later in a local hospital while undergoing surgery

Sandra Lee Scheuer; age 20; 390 ft (120 m) fatal neck wound; died a few minutes later from loss of blood

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Joseph Lewis, Jr.; 71 ft (22 m); hit twice in the right abdomen and left lower leg

John R. Cleary; 110 ft (34 m); upper left chest wound

Thomas Mark Grace; 225 ft (69 m); struck in left ankle

Alan Michael Canfora; 225 ft (69 m); hit in his right wrist

Dean R. Kahler; 300 ft (91 m); back wound fracturing the vertebrae, permanently paralyzed from the chest down

Douglas Alan Wrentmore; 329 ft (100 m); hit in his right knee

James Dennis Russell; 375 ft (114 m); hit in his right thigh from a bullet and in the right forehead by birdshot, both wounds minor

Robert Follis Stamps; 495 ft (151 m); hit in his right buttock

Donald Scott MacKenzie; 750 ft (230 m); neck wound

Memorial to Jeffrey Miller, taken from approximately the same perspective as John Filo's 1970 photograph, as it appeared in 2007.

I want to give props to marble falls and Siswan for their posts on this anniversary - please rec their OP's as well:

https://www.democraticunderground.com/1017540357

https://www.democraticunderground.com/100212070764

https://www.democraticunderground.com/100212070808

Explosion at Illinois silicone plant leaves 4 injured and 3 unaccounted

Source: CNN

(CNN)An explosion rocked parts of an Illinois town Friday night, leaving four people injured and three others unaccounted for, authorities said.

The blast happened at AB Specialty Silicones in Waukegan, about 40 miles north of Chicago, police said. The company describes itself as a manufacturer of specialty silicone chemicals.

The "catastrophic explosion" hit around 9:30 p.m. local time, said Cmdr. Joe Florip, a Waukegan police spokesman.

Three employees are unaccounted for, Waukegan Fire Marshal Steven Lenzi said.

Florip said he would "categorize this as a massive explosion." "Many neighboring properties are going to have damage," he said. The fire has been extinguished, and hazardous materials technicians and other teams are on the scene and searching, Lenzi said. No cause has been determined, and the state fire marshal will assist with an investigation, he said. Florip said the plant was open at the time of the explosion.

</snip>

Read more: https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/04/us/illinois-plant-explosion/index.html

Yikes!

77 Years Ago Today; The Battle of the Coral Sea begins

The American aircraft carrier USS Lexington explodes on 8 May 1942, several hours after being damaged by a Japanese carrier air attack.

The Battle of the Coral Sea, fought from 4–8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces from the United States and Australia, taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II. The battle is historically significant as the first action in which aircraft carriers engaged each other, as well as the first in which the opposing ships neither sighted nor fired directly upon one another.

In an attempt to strengthen their defensive position in the South Pacific, the Japanese decided to invade and occupy Port Moresby (in New Guinea) and Tulagi (in the southeastern Solomon Islands). The plan to accomplish this was called Operation MO, and involved several major units of Japan's Combined Fleet. These included two fleet carriers and a light carrier to provide air cover for the invasion forces. It was under the overall command of Japanese Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue.

The U.S. learned of the Japanese plan through signals intelligence, and sent two United States Navy carrier task forces and a joint Australian-U.S. cruiser force to oppose the offensive. These were under the overall command of U.S. Admiral Frank J. Fletcher.

On 3–4 May, Japanese forces successfully invaded and occupied Tulagi, although several of their supporting warships were sunk or damaged in surprise attacks by aircraft from the U.S. fleet carrier Yorktown. Now aware of the presence of U.S. carriers in the area, the Japanese fleet carriers advanced towards the Coral Sea with the intention of locating and destroying the Allied naval forces. On the evening of 6 May, the direction chosen for air searches by the opposing commanders brought the two carrier forces to within 70 nmi (81 mi; 130 km) of each other, unbeknownst to both sides. Beginning on 7 May, the carrier forces from the two sides engaged in airstrikes over two consecutive days. On the first day, both forces mistakenly believed they were attacking their opponent's fleet carriers, but were actually attacking other units, with the U.S. sinking the Japanese light carrier Shōhō while the Japanese sank a U.S. destroyer and heavily damaged a fleet oiler (which was later scuttled). The next day, the fleet carriers found and engaged each other, with the Japanese fleet carrier Shōkaku heavily damaged, the U.S. fleet carrier Lexington critically damaged (and later scuttled), and Yorktown damaged. With both sides having suffered heavy losses in aircraft and carriers damaged or sunk, the two forces disengaged and retired from the battle area. Because of the loss of carrier air cover, Inoue recalled the Port Moresby invasion fleet, intending to try again later.

Although a tactical victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk, the battle would prove to be a strategic victory for the Allies for several reasons. The battle marked the first time since the start of the war that a major Japanese advance had been checked by the Allies. More importantly, the Japanese fleet carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku—the former damaged and the latter with a depleted aircraft complement—were unable to participate in the Battle of Midway the following month, while Yorktown did participate, ensuring a rough parity in aircraft between the two adversaries and contributing significantly to the U.S. victory in that battle. The severe losses in carriers at Midway prevented the Japanese from reattempting to invade Port Moresby from the ocean and helped prompt their ill-fated land offensive over the Kokoda Track. Two months later, the Allies took advantage of Japan's resulting strategic vulnerability in the South Pacific and launched the Guadalcanal Campaign; this, along with the New Guinea Campaign, eventually broke Japanese defenses in the South Pacific and was a significant contributing factor to Japan's ultimate surrender in World War II.

41 Years Ago Today; The Birth of Spam (no, not the canned kind)

History

Pre-Internet

In the late 19th century, Western Union allowed telegraphic messages on its network to be sent to multiple destinations. The first recorded instance of a mass unsolicited commercial telegram is from May 1864, when some British politicians received an unsolicited telegram advertising a dentist.

History

The earliest documented spam (although the term had not yet been coined) was a message advertising the availability of a new model of Digital Equipment Corporation computers sent by Gary Thuerk to 393 recipients on ARPANET on May 3, 1978. Rather than send a separate message to each person, which was the standard practice at the time, he had an assistant, Carl Gartley, write a single mass email. Reaction from the net community was fiercely negative, but the spam did generate some sales.

Spamming had been practiced as a prank by participants in multi-user dungeon games, to fill their rivals' accounts with unwanted electronic junk.

The first major commercial spam incident started on March 5, 1994, when a husband and wife team of lawyers, Laurence Canter and Martha Siegel, began using bulk Usenet posting to advertise immigration law services. The incident was commonly termed the "Green Card spam", after the subject line of the postings. Defiant in the face of widespread condemnation, the attorneys claimed their detractors were hypocrites or "zealouts", claimed they had a free speech right to send unwanted commercial messages, and labeled their opponents "anti-commerce radicals". The couple wrote a controversial book entitled How to Make a Fortune on the Information Superhighway.

An early example of nonprofit fundraising bulk posting via Usenet also occurred in 1994 on behalf of CitiHope, an NGO attempting to raise funds to rescue children at risk during the Bosnian War. However, as it was a violation of their terms of service, the ISP Panix deleted all of the bulk posts from Usenet, only missing three copies[citation needed].

Within a few years, the focus of spamming (and anti-spam efforts) moved chiefly to email, where it remains today. By 1999, Khan C. Smith, a well known hacker at the time, had begun to commercialize the bulk email industry and rallied thousands into the business by building more friendly bulk email software and providing internet access illegally hacked from major ISPs such as Earthlink and Botnets.

By 2009, the majority of spam sent around the World was in the English language; spammers began using automatic translation services to send spam in other languages.

</snip>

56 Years Ago Today; The Birmingham AL police change tactics against Civil Rights Protesters

High school students are hit by a high-pressure water jet from a fire hose during a peaceful walk in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. As photographed by Charles Moore, images like this one, printed in Life, inspired international support for the demonstrators.

The Birmingham campaign, or Birmingham movement, was a movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama. Led by Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, Fred Shuttlesworth and others, the campaign of nonviolent direct action culminated in widely publicized confrontations between young black students and white civic authorities, and eventually led the municipal government to change the city's discrimination laws.

In the early 1960s, Birmingham was one of the most racially divided cities in the United States, both as enforced by law and culturally. Black citizens faced legal and economic disparities, and violent retribution when they attempted to draw attention to their problems. Martin Luther King Jr. called it the most segregated city in the country. Protests in Birmingham began with a boycott led by Shuttlesworth meant to pressure business leaders to open employment to people of all races, and end segregation in public facilities, restaurants, schools, and stores. When local business and governmental leaders resisted the boycott, SCLC agreed to assist. Organizer Wyatt Tee Walker joined Birmingham activist Shuttlesworth and began what they called Project C, a series of sit-ins and marches intended to provoke mass arrests.

When the campaign ran low on adult volunteers, James Bevel, SCLC's Director of Direct Action, thought of the idea of having students become the main demonstrators in the Birmingham campaign. He then trained and directed high school, college, and elementary school students in nonviolence, and asked them to participate in the demonstrations by taking a peaceful walk 50 at a time from the 16th Street Baptist Church to City Hall in order to talk to the mayor about segregation. This resulted in over a thousand arrests, and, as the jails and holding areas filled with arrested students, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water hoses and police attack dogs on the children and adult bystanders. Not all of the bystanders were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of SCLC to hold a completely nonviolent walk, but the students held to the nonviolent premise. Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC drew both criticism and praise for allowing children to participate and put themselves in harm's way.

The Birmingham campaign was a model of nonviolent direct action protest and, through the media, drew the world's attention to racial segregation in the South. It burnished King's reputation, ousted Connor from his job, forced desegregation in Birmingham, and directly paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibited racial discrimination in hiring practices and public services throughout the United States.

<snip>

Fire hoses and police dogs

When Connor realized that the Birmingham jail was full, on May 3 he changed police tactics to keep protesters out of the downtown business area. Another thousand students gathered at the church and left to walk across Kelly Ingram Park while chanting, "We're going to walk, walk, walk. Freedom ... freedom ... freedom." As the demonstrators left the church, police warned them to stop and turn back, "or you'll get wet". When they continued, Connor ordered the city's fire hoses, set at a level that would peel bark off a tree or separate bricks from mortar, to be turned on the children. Boys' shirts were ripped off, and young women were pushed over the tops of cars by the force of the water. When the students crouched or fell, the blasts of water rolled them down the asphalt streets and concrete sidewalks. Connor allowed white spectators to push forward, shouting, "Let those people come forward, sergeant. I want 'em to see the dogs work."

A.G. Gaston, who was appalled at the idea of using children, was on the phone with white attorney David Vann trying to negotiate a resolution to the crisis. When Gaston looked out the window and saw the children being hit with high-pressure water, he said, "Lawyer Vann, I can't talk to you now or ever. My people are out there fighting for their lives and my freedom. I have to go help them", and hung up the phone. Black parents and adults who were observing cheered on the marching students, but when the hoses were turned on, bystanders began to throw rocks and bottles at the police. To disperse them, Connor ordered police to use German shepherd dogs to keep them in line. James Bevel wove in and out of the crowds warning them, "If any cops get hurt, we're going to lose this fight." At 3 p.m., the protest was over. During a kind of truce, protesters went home. Police removed the barricades and re-opened the streets to traffic. That evening King told worried parents in a crowd of a thousand, "Don't worry about your children who are in jail. The eyes of the world are on Birmingham. We're going on in spite of dogs and fire hoses. We've gone too far to turn back."

Images of the day

Bill Hudson's image of Parker High School student Walter Gadsden being attacked by dogs was published in The New York Times on May 4, 1963.

A battle-hardened Huntley-Brinkley reporter later said that no military action he had witnessed had ever frightened or disturbed him as much as what he saw in Birmingham. Two out-of-town photographers in Birmingham that day were Charles Moore, who had previously worked with the Montgomery Advertiser and was now working for Life magazine, and Bill Hudson, with the Associated Press. Moore was a Marine combat photographer who was "jarred" and "sickened" by the use of children and what the Birmingham police and fire departments did to them. Moore was hit in the ankle by a brick meant for the police. He took several photos that were printed in Life. The first photo Moore shot that day showed three teenagers being hit by a water jet from a high-pressure firehose. It was titled "They Fight a Fire That Won't Go Out". A shorter version of the caption was later used as the title for Fred Shuttlesworth's biography. The Life photo became an "era-defining picture" and was compared to the photo of Marines raising the U.S. flag on Iwo Jima. Moore suspected that the film he shot "was likely to obliterate in the national psyche any notion of a 'good southerner'." Hudson remarked later that his only priorities that day were "making pictures and staying alive" and "not getting bit by a dog."

Right in front of Hudson stepped Parker High School senior Walter Gadsden when a police officer grabbed the young man's sweater and a police dog charged him. Gadsden had been attending the demonstration as an observer. He was related to the editor of Birmingham's black newspaper, The Birmingham World, who strongly disapproved of King's leadership in the campaign. Gadsden was arrested for "parading without a permit", and after witnessing his arrest, Commissioner Connor remarked to the officer, "Why didn't you bring a meaner dog; this one is not the vicious one." Hudson's photo of Gadsden and the dog ran across three columns in the prominent position above the fold on the front page of The New York Times on May 4, 1963.

Television cameras broadcast to the nation the scenes of fire hoses knocking down schoolchildren and police dogs attacking unprotected demonstrators. Such coverage and photos were given credit for shifting international support to the protesters and making Bull Connor "the villain of the era". President Kennedy told a group of people at the White House that The New York Times photo made him "sick". Kennedy called the scenes "shameful" and said that they were "so much more eloquently reported by the news camera than by any number of explanatory words."

The images also had a profound effect in Birmingham. Despite decades of disagreements, when the photos were released, "the black community was instantaneously consolidated behind King", according to David Vann, who would later serve as mayor of Birmingham. Horrified at what the Birmingham police were doing to protect segregation, New York Senator Jacob K. Javits declared, "the country won't tolerate it", and pressed Congress to pass a civil rights bill. Similar reactions were reported by Kentucky Senator Sherman Cooper, and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse, who compared Birmingham to South Africa under apartheid. A New York Times editorial called the behavior of the Birmingham police "a national disgrace." The Washington Post editorialized, "The spectacle in Birmingham ... must excite the sympathy of the rest of the country for the decent, just, and reasonable citizens of the community, who have so recently demonstrated at the polls their lack of support for the very policies that have produced the Birmingham riots. The authorities who tried, by these brutal means, to stop the freedom marchers do not speak or act in the name of the enlightened people of the city." President Kennedy sent Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall to Birmingham to help negotiate a truce. Marshall faced a stalemate when merchants and protest organizers refused to budge.

</snip>

Someone put a plastic chicken and empty KFC buckets in front of Barr's unoccupied chair!!

Looking for pics now... ![]()

8 Years Ago Today; Osama bin Laden is killed by US Special Forces

Osama bin Laden's compound

Osama bin Laden, the founder and first leader of the Islamist group Al-Qaeda, was killed in Pakistan on May 2, 2011, shortly after 1:00 am PKT (20:00 UTC, May 1) by United States Navy SEALs of the U.S. Naval Special Warfare Development Group (also known as DEVGRU or SEAL Team Six). The operation, code-named Operation Neptune Spear, was carried out in a CIA-led operation with Joint Special Operations Command, commonly known as JSOC, coordinating the Special Mission Units involved in the raid. In addition to SEAL Team Six, participating units under JSOC included the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne)—also known as "Night Stalkers"—and operators from the CIA's Special Activities Division, which recruits heavily from former JSOC Special Mission Units. The operation ended a nearly 10-year search for bin Laden, following his role in the September 11 attacks on the United States.

The raid on bin Laden's compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan was launched from Afghanistan. U.S. military officials said that after the raid U.S. forces took the body of bin Laden to Afghanistan for identification, then buried it at sea within 24 hours of his death in accordance with Islamic tradition.

Al-Qaeda confirmed the death on May 6 with posts made on militant websites, vowing to avenge the killing. Other Pakistani militant groups, including the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, vowed retaliation against the U.S. and against Pakistan for not preventing the operation. The raid was supported by over 90% of the American public, was welcomed by the United Nations, NATO, the European Union and a large number of governments, but was condemned by others, including two-thirds of the Pakistani public. Legal and ethical aspects of the killing, such as his not being taken alive despite being unarmed, were questioned by others, including Amnesty International. Also controversial was the decision not to release any photographic or DNA evidence of bin Laden's death to the public.

In the aftermath of the killing, Pakistani Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani formed a commission under Senior Justice Javed Iqbal to investigate the circumstances surrounding the attack. The resulting Abbottabad Commission Report, which revealed Pakistani state military and intelligence authorities' "collective failure" that enabled bin Laden to hide in Pakistan for nine years, was leaked to Al Jazeera on July 8, 2013.

<snip>

Planning and final decision

The CIA briefed Vice Admiral William H. McRaven, the commander of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), about the compound in January 2011. McRaven said a commando raid would be fairly straightforward but he was concerned about the Pakistani response. He assigned a captain from the U.S. Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU) to work with a CIA team at their campus in Langley, Virginia. The captain, named "Brian", set up an office in the printing plant in the CIA's Langley compound and, with six other JSOC officers, began to plan the raid. Administration attorneys considered legal implications and options before the raid.

In addition to a helicopter raid, planners considered attacking the compound with B-2 Spirit stealth bombers. They also considered a joint operation with Pakistani forces. Obama decided that the Pakistani government and military could not be trusted to maintain operational security for the operation against bin Laden. "There was a real lack of confidence that the Pakistanis could keep this secret for more than a nanosecond," a senior adviser to the President told The New Yorker.

Obama met with the National Security Council on March 14 to review the options; he was concerned that the mission would be exposed and wanted to proceed quickly. For that reason he ruled out involving the Pakistanis. Defense Secretary Robert Gates and other military officials expressed doubts as to whether bin Laden was in the compound, and whether a commando raid was worth the risk. At the end of the meeting, the president seemed to be leaning toward a bombing mission. Two U.S. Air Force officers were tasked with exploring that option further.

The CIA was unable to rule out the existence of an underground bunker below the compound. Presuming that one existed, 32 2,000-pound (910 kg) bombs fitted with JDAM guidance systems would be required to destroy it. With that amount of ordnance, at least one other house was in the blast radius. Estimates were that up to a dozen civilians would be killed in addition to those in the compound. Furthermore, it was unlikely there would be enough evidence remaining to prove that bin Laden was dead. Presented with this information at the next Security Council meeting on March 29, Obama put the bombing plan on hold. Instead he directed Admiral McRaven to develop the plan for a helicopter raid. The U.S. intelligence community also studied an option of hitting bin Laden with a drone-fired small tactical munition as he paced in his compound's vegetable garden.

McRaven hand-picked a team drawing from the most experienced and senior operators from Red Squadron, one of four that make up DEVGRU. Red Squadron was coming home from Afghanistan and could be redirected without attracting attention. The team had language skills and experience with cross-border operations into Pakistan. Almost all of the Red Squadron operators had 10 or more deployments to Afghanistan.

Without being told the exact nature of their mission, the team performed rehearsals of the raid in two locations in the U.S.—around April 10 at Harvey Point Defense Testing Activity facility in North Carolina where a 1:1 version of bin Laden's compound was built, and April 18 in Nevada. The location in Nevada was at 4,000 feet (1,200 m) elevation—chosen to test the effects the altitude would have on the raiders' helicopters. The Nevada mock-up used chain-link fences to simulate the compound walls, which left the U.S. participants unaware of the potential effects of the high compound walls on the helicopters' lift capabilities.

Planners believed the SEALs could get to Abbottabad and back without being challenged by the Pakistani military. The helicopters to be used in the raid had been designed to be quiet and to have low radar visibility. Since the U.S. had helped equip and train the Pakistanis, their defensive capabilities were known. The U.S. had supplied F-16 Fighting Falcons to Pakistan on the condition they were kept at a Pakistani military base under 24-hour U.S. surveillance.

If bin Laden surrendered, he would be held near Bagram Air Base. If the SEALs were discovered by the Pakistanis in the middle of the raid, Joint Chiefs Chairman Admiral Mike Mullen would call Pakistan's army chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and try to negotiate their release.

When the National Security Council (NSC) met again on April 19, Obama gave provisional approval for the helicopter raid. He was worried that the plan for dealing with the Pakistanis was too uncertain, Obama asked Admiral McRaven to equip the team to fight its way out if necessary.

McRaven and the SEALs left for Afghanistan to practice at a one-acre, full-scale replica of the compound built on a restricted area of Bagram known as Camp Alpha. The team departed the U.S. from Naval Air Station Oceana on April 26 in a C-17 aircraft, refueled on the ground at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, landed at Bagram Air Base, then moved to Jalalabad on April 27.

On April 28, Admiral Mullen explained the final plan to the NSC. To bolster the "fight your way out" scenario, Chinook helicopters with additional troops would be positioned nearby. Most of the advisers in the meeting supported going forward with the raid. Only Vice President Biden completely opposed it. Gates advocated using the drone missile option, but changed his support the next day to the helicopter raid plan. Obama said he wanted to speak directly to Admiral McRaven before he gave the order to proceed. The president asked if McRaven had learned anything since arriving in Afghanistan that caused him to lose confidence in the mission. McRaven told him the team was ready and that the next few nights would have little moonlight over Abbottabad, good conditions for a raid.

On April 29 at 8:20 a.m. EDT, Obama conferred with his advisers and gave the final go-ahead. The raid would take place the following day. That evening the president was informed that the operation would be delayed one day due to cloudy weather.

On April 30, Obama called McRaven one more time to wish the SEALs well and to thank them for their service. That evening, the President attended the annual White House Correspondent's Association dinner, which was hosted by comedian and television actor Seth Meyers. At one point, Meyers joked: "People think bin Laden is hiding in the Hindu Kush, but did you know that every day from 4 to 5 he hosts a show on C-SPAN?" Obama laughed, despite his knowledge of the operation to come.

On May 1 at 1:22 p.m., Panetta, acting on the president's orders, directed McRaven to move forward with the operation. Shortly after 3 p.m., the president joined national security officials in the Situation Room to monitor the raid. They watched night-vision images taken from a Sentinel drone while Panetta, appearing in a corner of the screen from CIA headquarters, narrated what was happening. Video links with Panetta at CIA headquarters and McRaven in Afghanistan were set up in the Situation Room. In an adjoining office was the live drone feed presented on a laptop computer operated by Brigadier General Marshall Webb, assistant commander of JSOC. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was one of those in the Situation Room, and described it like this: "Contrary to some news reports and what you see in the movies, we had no means to see what was happening inside the building itself. All we could do was wait for an update from the team on the ground. I looked at the President. He was calm. Rarely have I been prouder to serve by his side as I was that day." Two other command centers monitored the raid from the Pentagon and the U.S. embassy in Islamabad.

<snip>

Killing of bin Laden

The SEALs encountered bin Laden on the third floor of the main building. Bin Laden was "wearing the local loose-fitting tunic and pants known as a kurta paijama", which were later found to have €500 and two phone numbers sewn into the fabric.

Bin Laden peered through his bedroom door at the Americans advancing up the stairs, and the lead SEAL fired at him. Reports differ, though agree eventually he was hit by shots to the body and head. The initial shots either missed, hit him in the side, or hit him in the head. One of bin Laden's wives, Amal Ahmed Abdul Fatah, motioned as if she were about to charge. The lead SEAL shot her in the leg, then grabbed both women and shoved them aside.

Robert J. O'Neill, who later publicly identified himself as one of the SEALs who shot bin Laden, states that he pushed past the lead SEAL, entered through the door and confronted bin Laden inside the bedroom. O'Neill states that bin Laden was standing behind a woman with his hands on her shoulders, pushing her forward. O'Neill immediately shot bin Laden twice in the forehead, then once more as bin Laden crumpled to the floor.

Matt Bissonnette, gives a conflicting account of the situation. In Bissonnette's version, Bin Laden had already been mortally wounded by the lead SEAL's shots from the staircase. The lead SEAL then pushed Bin Laden's wives aside, attempting to shield the SEALs behind him in the case that either woman had an explosive device. After Bin Laden staggered back or fell into the bedroom, Bissonnette and O'Neill entered the room, saw the wounded Bin Laden on the ground, fired multiple rounds, and killed him. Journalist Peter Bergen investigated the conflicting claims and found that most of the SEALs present during the raid favored Bissonnette's account of the events. According to Bergen's sources, O'Neill did not mention firing the shots that killed Bin Laden in the after action report following the operations.

The weapon used to kill bin Laden was an HK416 using 5.56mm NATO 77-grain OTM (open-tip match) rounds made by Black Hills Ammunition. The SEAL team leader radioed, "For God and country—Geronimo, Geronimo, Geronimo" and then, after being prompted by McRaven for confirmation, "Geronimo EKIA" (enemy killed in action). Watching the operation in the White House Situation Room, Obama simply said, "We got him."

In these reports, there were said to be two weapons near bin Laden in his room, including an AKS-74U carbine and a Russian-made Makarov pistol, but according to his wife Amal, he was shot before he could reach his AKS-74U. According to the Associated Press, the guns were on a shelf next to the door and the SEALs did not see them until they were photographing the body.

As the SEALs encountered women and children during the raid, they restrained them with plastic handcuffs or zip ties. After the raid was over, U.S. forces moved the surviving residents outside "for Pakistani forces to discover". The injured Amal Ahmed Abdul Fatah continued to harangue the raiders in Arabic. Bin Laden's 12-year-old daughter Safia was allegedly struck in her foot or ankle by a piece of flying debris.

While bin Laden's body was taken by U.S. forces, the bodies of the four others killed in the raid were left behind at the compound and later taken into Pakistani custody.

</snip>

If Trump were POTUS then, bin Laden would still be alive after the bin Laden family "loaned" Trump and Jared money.

50 Years Ago Today; The Queen Elizabeth 2 sets off on her Maiden Voyage

Last visit to the River Clyde, Glasgow, Scotland, near to where she was constructed, 2008

Queen Elizabeth 2, often referred to simply as QE2, is a floating hotel and retired ocean liner built for the Cunard Line which was operated by Cunard as both a transatlantic liner and a cruise ship from 1969 to 2008. Since 18 April 2018, she has been operating as a floating hotel in Dubai.

QE2 was designed for the transatlantic service from her home port of Southampton, UK to New York, and she was named after the earlier Cunard liner RMS Queen Elizabeth. She served as the flagship of the line from 1969 until succeeded by RMS Queen Mary 2 in 2004. QE2 was designed in Cunard's offices in Liverpool and Southampton and built in Clydebank, Scotland. She was considered the last of the great transatlantic ocean liners until Queen Mary 2 entered service.

QE2 was also the last oil-fired passenger steamship to cross the Atlantic in scheduled liner service until she was refitted with a modern diesel powerplant in 1986-87. She undertook regular world cruises during almost 40 years of service, and later operated predominantly as a cruise ship, sailing out of Southampton, England. QE2 had no running mate and never ran a year-round weekly transatlantic express service to New York. She did, however, continue the Cunard tradition of regular scheduled transatlantic crossings every year of her service life. QE2 was never given a Royal Mail Ship designation, instead carrying the SS and later MV or MS prefixes in official documents.

QE2 was retired from active Cunard service on 27 November 2008. She had been acquired by the private equity arm of Dubai World, which planned to begin conversion of the vessel to a 500-room floating hotel moored at the Palm Jumeirah, Dubai. The 2008 financial crisis intervened, however, and the ship was laid up at Dubai Drydocks and later Port Rashid. Subsequent conversion plans were announced by in 2012 and by the Oceanic Group in 2013[9] but these both stalled. In November, 2015 Cruise Arabia & Africa quoted DP World chairman Ahmed Sultan Bin Sulayem as saying that QE2 would not be scrapped[10] and a Dubai-based construction company announced in March, 2017 that it had been contracted to refurbish the ship. The restored QE2 opened to visitors on 18 April 2018, with a soft opening. The grand opening was set for October 2018.

<snip>

Early career

Queen Elizabeth 2's maiden voyage, from Southampton to New York, commenced on 2 May 1969, taking 4 days, 16 hours, and 35 minutes.

In 1971, she participated in the rescue of some 500 passengers from the burning French Line ship Antilles. On 5 March 1971 she was disabled for four hours when jellyfish were sucked into and blocked her seawater intakes.

On 17 May 1972, while travelling from New York to Southampton, she was the subject of a bomb threat.[18] She was searched by her crew, and a combined Special Air Service and Special Boat Service team which parachuted into the sea to conduct a search of the ship. No bomb was found, but the hoaxer was arrested by the FBI.

QE2 in Southampton, 1976

The following year QE2 undertook two chartered cruises through the Mediterranean to Israel in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the state's founding. The ship's Columbia Restaurant was koshered for Passover, and Jewish passengers were able to celebrate Passover on the ship. According to the book "The Angel" by Uri Bar-Joseph, Muammar Gaddafi ordered a submarine to torpedo her during one of the chartered cruises in retaliation for Israel's downing of Libyan Flight 114, but Anwar Sadat intervened secretly to foil the attack.

On 23 July 1976 while Queen Elizabeth 2 was 80 miles off the Scilly Isles on a transatlantic voyage, a flexible coupling drive connecting the starboard main engine high pressure rotor and the reduction gear box ruptured. This allowed lubricating oil under pressure to enter into the main engine room where it ignited, creating a severe fire. It took 20 minutes to bring the fire under control. Reduced down to two boilers, the ship limped back to Southampton. Damage from the fire resulted in a replacement boiler having to be fitted by dry-docking the ship and cutting an access hole in her side.

By 1978 Queen Elizabeth 2 was breaking even with an occupancy of 65%, generating revenues of greater than 30 million per year against which had to be deducted an annual fuel cost of ₤5 million and a monthly crew cost of ₤225,000. With it costing ₤80,000 a day for her to sit idle in port, her owners made every attempt to keep her at sea and full of passengers. As a result, as much maintenance as possible was undertaken while at sea. However, she needed all three of her boilers to be in service if she was to maintain her transatlantic schedule. With limited ability to maintain her boilers, reliability was becoming a serious issue.

Falklands War

On 3 May 1982, she was requisitioned by the British government for service as a troop carrier in the Falklands War.

In preparation for war service, Vosper Thornycroft commenced in Southampton on 5 May 1982 the installation of two helicopter pads, the transformation of public lounges into dormitories, the installation of fuel pipes that ran through the ship down to the engine room to allow for refuelling at sea, and the covering of carpets with 2,000 sheets of hardboard. A quarter of the ship's length was reinforced with steel plating, and an anti-magnetic coil was fitted to combat naval mines. Over 650 Cunard crew members volunteered for the voyage, to look after the 3,000 members of the Fifth Infantry Brigade, which the ship transported to South Georgia.

On 12 May 1982, with only one of her three boilers in operation, the ship departed Southampton for the South Atlantic, carrying 3,000 troops and 650 volunteer crew. The remaining boilers were brought back into service as she steamed south.

During the voyage, the ship was blacked out and the radar switched off to avoid detection, steaming on without modern aids.

Berthed in Málaga Spain 1982, with her original white funnel repainted red. Her hull is painted grey, a short lived decision

Queen Elizabeth 2 returned to the UK on 11 June 1982, where she was greeted in Southampton Water by The Queen Mother on board the Royal Yacht Britannia. Peter Jackson, the captain of the QE2 responded to the Queen Mother's welcome: "Please convey to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth our thanks for her kind message. Cunard's Queen Elizabeth 2 is proud to have been of service to Her Majesty's Forces." The ship underwent conversion back to passenger service, with her funnel being painted in the traditional Cunard orange with black stripes which are known as "Hands" for the first time, during the refit the hull's exterior was repainted an unconventional light pebble grey. She returned to service on 7 August 1982.

The new colour scheme proved unpopular with passengers, as well as difficult to maintain and so the hull reverted to traditional colours in 1983. Later that year, QE2 was fitted with a magrodome over her Quarter Deck pool.

Diesel era and Project Lifestyle

QE2’s new and wider funnel

QE2 once again experienced mechanical problems following her annual overhaul in November 1983. Boiler problems caused Cunard to cancel a cruise, and, in October 1984, an electrical fire caused a complete loss of power. The ship was delayed for several days before power could be restored. Instead of replacing the QE2 with a newer vessel, Cunard decided that it was more prudent to simply make improvements to her. Therefore, from 27 October 1986 to 25 April 1987,[44] QE2 underwent one of her most significant refurbishments when she was converted by Lloyd Wert at their shipyard in Bremerhaven, Germany from steam power to diesel. Nine MAN B&W diesel electric engines, new propellers and a heat recovery system (to utilise heat expelled by the engines) were fitted, which halved the fuel consumption. With this new propulsion system, QE2 was expected to serve another 20 years with Cunard. The passenger accommodation was also modernised. The refurbishment cost over ₤100 million.

On 7 August 1992, the underside of the hull was extensively damaged when she ran aground south of Cuttyhunk Island near Martha's Vineyard, while returning from a five-day cruise to Halifax, Nova Scotia along the east coast of the United States and Canada. A combination of her speed, an uncharted shoal and underestimating the increase in the ship's draft due to the effect of squat led to the ship's hull scraping rocks on the ocean floor. The accident resulted in the passengers disembarking earlier than scheduled at nearby Newport, Rhode Island and the ship being taken out of service while temporary repairs were made in drydock at Boston. Several days later, divers found the red paint from the keel on previously uncharted rocks where the ship struck the bottom.

By the mid 1990s, it was decided that QE2 was due for a new look and in 1994 the ship was given a multimillion-pound refurbishment in Hamburg code named Project Lifestyle.

On 11 September 1995, QE2 encountered a rogue wave, estimated at 90 ft (27 m), caused by Hurricane Luis in the North Atlantic Ocean about 200 miles south of eastern Newfoundland. One year later, during her twentieth world cruise, she completed her four millionth mile. The ship had sailed the equivalent of 185 times around the planet.

QE2 celebrated the 30th anniversary of her maiden voyage in Southampton in 1999. In three decades she had 1,159 voyages, sailed 4,648,050 nautical miles (5,348,880 mi; 8,608,190 km) and carried over two million passengers.

</snip>

37 Years Ago Today; A Pearl Harbor Survivor is sunk by the Royal Navy

ARA General Belgrano underway

ARA General Belgrano was an Argentine Navy light cruiser in service from 1951 until 1982.

Originally commissioned by the U.S. as USS Phoenix, she saw action in the Pacific theatre of World War II before being sold by the United States Navy to Argentina. The vessel was the second to have been named after the Argentine founding father Manuel Belgrano (1770–1820). The first vessel was a 7,069-ton armoured cruiser completed in 1896.

She was sunk on 2 May 1982 during the Falklands War by the Royal Navy submarine Conqueror with the loss of 323 lives. Losses from General Belgrano totalled just over half of Argentine military deaths in the war.

She is the only ship to have been sunk during military operations by a nuclear-powered submarine and the second sunk in action by any type of submarine since World War II, the first being the Indian frigate INS Khukri, which was sunk by the Pakistani submarine PNS Hangor during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War.

Early Career

Phoenix at Pearl Harbor in 1941

The warship was built as USS Phoenix, the sixth ship of the Brooklyn-class cruiser design, in Camden, New Jersey, by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation starting in 1935, and launched in March 1938. She survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 undamaged, and went on to earn nine battle stars for World War II service. At the end of the war, she was placed in reserve at Philadelphia on 28 February 1946, decommissioned on 3 July that year and remained laid up at Philadelphia.

Phoenix was sold to Argentina in October 1951 and renamed 17 de Octubre after the "People's Loyalty day", an important symbol for the political party of the then-president Juan Perón. Sold with her was another of her class, the USS Boise, renamed ARA Nueve de Julio, which was withdrawn in 1977.

17 de Octubre was one of the main naval units that joined the 1955 coup in which Perón was overthrown, and was renamed General Belgrano after General Manuel Belgrano, who founded the Escuela de Náutica (School of Navigation) in 1799 and had fought for Argentine independence from 1811 to 1819. General Belgrano accidentally rammed her sister ship Nueve de Julio on exercises in 1956, which resulted in damage to both. General Belgrano was outfitted with the Sea Cat anti-aircraft missile system between 1967 and 1968.

<snip>

Sinking

After the 1982 invasion of the Falkland Islands, on 2 April 1982 Britain declared a Maritime Exclusion Zone (MEZ) of 200 nautical miles around the Falkland Islands within which any Argentine warship or naval auxiliary entering the MEZ might be attacked by British nuclear-powered submarines (SSN).

On 23 April, the British Government clarified in a message that was passed via the Swiss Embassy in Buenos Aires to the Argentine government that any Argentine ship or aircraft that was considered to pose a threat to British forces would be attacked.

On 30 April this was upgraded to the total exclusion zone, within which any sea vessel or aircraft from any country entering the zone might be fired upon without further warning. The zone was stated to be "...without prejudice to the right of the United Kingdom to take whatever additional measures may be needed in exercise of its right of self-defence, under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter." The concept of a total exclusion zone was a novelty in maritime law; the Law of the Sea Convention had no provision for such an instrument. Its purpose seems to have been to increase the amount of time available to ascertain whether any vessel in the zone was hostile or not. Regardless of the uncertainty of the zone's legal status it was widely respected by the shipping of neutral nations.

The Argentine military junta began to reinforce the islands in late April when it was realised that the British Task Force was heading south. As part of these movements, Argentine Naval units were ordered to take positions around the islands. Two Task Groups designated 79.1, which included the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo plus two Type 42 destroyers, and 79.2, which included three Exocet missile armed Drummond-class corvettes, both sailed to the north. General Belgrano had left Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego on 26 April. Two destroyers, ARA Piedra Buena and ARA Hipólito Bouchard (also ex-USN vessels) were detached from Task Group 79.2 and together with the tanker YPF Puerto Rosales, joined General Belgrano to form Task Group 79.3.

By 29 April, the ships were patrolling the Burdwood Bank, south of the islands. On 30 April, General Belgrano was detected by the British nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine Conqueror. The submarine approached over the following day. On 1 May 1982, Admiral Juan Lombardo ordered all Argentine naval units to seek out the British task force around the Falklands and launch a "massive attack" the following day. General Belgrano, which was outside and to the south-west of the exclusion zone, was ordered south-east.

Lombardo's signal was intercepted by British Intelligence. As a result, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her War Cabinet, meeting at Chequers the following day, agreed to a request from Admiral Terence Lewin, the Chief of the Defence Staff, to alter the rules of engagement and allow an attack on General Belgrano outside the exclusion zone. Although the group was outside the British-declared total exclusion zone of 370 km (200 nautical miles) radius from the islands, the British decided that it was a threat. After consultation at Cabinet level, Thatcher agreed that Commander Chris Wreford-Brown should attack General Belgrano.

At 15:57 (Falkland Islands Time)[N 1] on 2 May, Conqueror fired three 21 inch Mk 8 mod 4 torpedoes (conventional, non-guided, torpedoes), each with an 805-pound (363 kg) Torpex warhead. While Conqueror was also equipped with the newer Mark 24 Tigerfish homing torpedo, there were doubts about its reliability. Initial reports from Argentina claimed that Conqueror fired two Tigerfish torpedoes on General Belgrano. Two of the three torpedoes hit General Belgrano. According to the Argentine government, General Belgrano's position was 55°24?S 61°32?WCoordinates: 55°24?S 61°32?W.

One of the torpedoes struck 10 to 15 metres (33 to 49 ft) aft of the bow, outside the area protected by either the ship's side armour or the internal anti-torpedo bulge. This blew off the ship's bow, but the internal torpedo bulkheads held and the forward powder magazine for the 40 mm gun did not detonate. It is believed that none of the ship's company were in that part of the ship at the time of the explosion.

The second torpedo struck about three-quarters of the way along the ship, just outside the rear limit of the side armour plating. The torpedo punched through the side of the ship before exploding in the aft machine room. The explosion tore upward through two messes and a relaxation area called "the Soda Fountain" before finally ripping a 20-metre-long hole in the main deck. Later reports put the number of deaths in the area around the explosion at 275 men. After the explosion, the ship rapidly filled with smoke. The explosion also damaged General Belgrano's electrical power system, preventing her from putting out a radio distress call. Though the forward bulkheads held, water was rushing in through the hole created by the second torpedo and could not be pumped out because of the electrical power failure. In addition, although the ship should have been "at action stations", she was sailing with the water-tight doors open.

The ship began to list to port and to sink towards the bow. Twenty minutes after the attack, at 16:24, Captain Bonzo ordered the crew to abandon ship. Inflatable life rafts were deployed, and the evacuation began without panic.

General Belgrano, sinking

The two escort ships were unaware of what was happening to General Belgrano, as they were out of touch with her in the gloom and had not seen the distress rockets or lamp signals. Adding to the confusion, the crew of Bouchard felt an impact that was possibly the third torpedo striking at the end of its run (an examination of the ship later showed an impact mark consistent with a torpedo). The two ships continued on their course westward and began dropping depth charges. By the time the ships realised that something had happened to General Belgrano, it was already dark and the weather had worsened, scattering the life rafts.

Argentine and Chilean ships rescued 772 men in all from 3 to 5 May. In total, 323 were killed in the attack: 321 members of the crew and two civilians who were on board at the time.

</snip>

88 Years Ago Today; A Skyscraper Icon is Dedicated

Construction

Demolition of the old Waldorf–Astoria began on October 1, 1929. Stripping the building down was an arduous process, as the hotel had been constructed using more rigid material than earlier buildings had been. Furthermore, the old hotel's granite, wood chips, and "'precious' metals such as lead, brass, and zinc" were not in high demand resulting in issues with disposal. Most of the wood was deposited into a woodpile on nearby 30th Street or was burned in a swamp elsewhere. Much of the other materials that made up the old hotel, including the granite and bronze, were dumped into the Atlantic Ocean near Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

By the time the hotel's demolition started, Raskob had secured the required funding for the construction of the building. The plan was to start construction later that year but, on October 24, the New York Stock Exchange suffered a sudden crash marking the beginning of the decade-long Great Depression. Despite the economic downturn, Raskob refused to cancel the project because of the progress that had been made up to that point. Neither Raskob, who had ceased speculation in the stock market the previous year, nor Smith, who had no stock investments, suffered financially in the crash. However, most of the investors were affected and as a result, in December 1929, Empire State Inc. obtained a $27.5 million loan from Metropolitan Life Insurance Company so construction could begin. The stock market crash resulted in no demand in new office space, Raskob and Smith nonetheless started construction, as canceling the project would have resulted in greater losses for the investors.

A worker bolts beams during construction; the Chrysler Building can be seen in the background.

A structural steel contract was awarded on January 12, 1930, with excavation of the site beginning ten days later on January 22, before the old hotel had been completely demolished. Two twelve-hour shifts, consisting of 300 men each, worked continuously to dig the 55-foot (17 m) foundation. Small pier holes were sunk into the ground to house the concrete footings that would support the steelwork. Excavation was nearly complete by early March, and construction on the building itself started on March 17, with the builders placing the first steel columns on the completed footings before the rest of the footings had been finished. Around this time, Lamb held a press conference on the building plans. He described the reflective steel panels parallel to the windows, the large-block Indiana Limestone facade that was slightly more expensive than smaller bricks, and the tower's lines and rise. Four colossal columns, intended for installation in the center of the building site, were delivered; they would support a combined 10,000,000 pounds (4,500,000 kg) when the building was finished.

The structural steel was pre-ordered and pre-fabricated in anticipation of a revision to the city's building code that would have allowed the Empire State Building's structural steel to carry 18,000 pounds per square inch (124,106 kPa), up from 16,000 pounds per square inch (110,316 kPa), thus reducing the amount of steel needed for the building. Although the 18,000-psi regulation had been safely enacted in other cities, Mayor Jimmy Walker did not sign the new codes into law until March 26, 1930, just before construction was due to commence. The first steel framework was installed on April 1, 1930. From there, construction proceeded at a rapid pace; during one stretch of 10 working days, the builders erected fourteen floors. This was made possible through precise coordination of the building's planning, as well as the mass production of common materials such as windows and spandrels. On one occasion, when a supplier could not provide timely delivery of dark Hauteville marble, Starrett switched to using Rose Famosa marble from a German quarry that was purchased specifically to provide the project with sufficient marble.

The scale of the project was massive, with trucks carrying "16,000 partition tiles, 5,000 bags of cement, 450 cubic yards [340 m3] of sand and 300 bags of lime" arriving at the construction site every day. There were also cafes and concession stands on five of the incomplete floors so workers did not have to descend to the ground level to eat lunch. Temporary water taps were also built so workers did not waste time buying water bottles from the ground level. Additionally, carts running on a small railway system transported materials from the basement storage to elevators that brought the carts to the desired floors where they would then be distributed throughout that level using another set of tracks. The 57,480 short tons (51,320 long tons) of steel ordered for the project was the largest-ever single order of steel at the time, comprising more steel than was ordered for the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street combined. According to historian John Tauranac, building materials were sourced from numerous, and distant, sources with "limestone from Indiana, steel girders from Pittsburgh, cement and mortar from upper New York State, marble from Italy, France, and England, wood from northern and Pacific Coast forests, [and] hardware from New England." The facade, too, used a variety of material, most prominently Indiana limestone but also Swedish black granite, terracotta, and brick.

By June 20, the skyscraper's supporting steel structure had risen to the 26th floor, and by July 27, half of the steel structure had been completed. Starrett Bros. and Eken endeavored to build one floor a day in order to speed up construction, a goal that they almost reached with their pace of 4 1?2 stories per week; prior to this, the fastest pace of construction for a building of similar height had been 3 1?2 stories per week. While construction progressed, the final designs for the floors were being designed from the ground up (as opposed to the general design, which had been from the roof down). Some of the levels were still undergoing final approval, with several orders placed within an hour of a plan being finalized. On September 10, as steelwork was nearing completion, Smith laid the building's cornerstone during a ceremony attended by thousands. The stone contained a box with contemporary artifacts including the previous day's New York Times, a U.S. currency set containing all denominations of notes and coins minted in 1930, a history of the site and building, and photographs of the people involved in construction. The steel structure was topped out at 1,048 feet (319 m) on September 19, twelve days ahead of schedule and 23 weeks after the start of construction. Workers raised a flag atop the 86th floor to signify this milestone.

Afterward, work on the building's interior and crowning mast commenced. The mooring mast topped out on November 21, two months after the steelwork had been completed. Meanwhile, work on the walls and interior was progressing at a quick pace, with exterior walls built up to the 75th floor by the time steelwork had been built to the 95th floor. The majority of the facade was already finished by the middle of November. Because of the building's height, it was deemed infeasible to have many elevators or large elevator cabins, so the builders contracted with the Otis Elevator Company to make 66 cars that could speed at 1,200 feet per minute (366 m/min), which represented the largest-ever elevator order at the time.

In addition to the time constraint builders had, there were also space limitations because construction materials had to be delivered quickly, and trucks needed to drop off these materials without congesting traffic. This was solved by creating a temporary driveway for the trucks between 33rd and 34th Streets, and then storing the materials in the building's first floor and basements. Concrete mixers, brick hoppers, and stone hoists inside the building ensured that materials would be able to ascend quickly and without endangering or inconveniencing the public. At one point, over 200 trucks made material deliveries at the building site every day. A series of relay and erection derricks, placed on platforms erected near the building, lifted the steel from the trucks below and installed the beams at the appropriate locations. The Empire State Building was structurally completed on April 11, 1931, twelve days ahead of schedule and 410 days after construction commenced. Al Smith shot the final rivet, which was made of solid gold.

A photograph of a cable worker, taken by Lewis Hine as part of his project to document the Empire State Building's construction

The project involved more than 3,500 workers at its peak, including 3,439 on a single day, August 14, 1930. Many of the workers were Irish and Italian immigrants, with a sizable minority of Mohawk ironworkers from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal. According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction, although the New York Daily News gave reports of 14 deaths[3] and a headline in the socialist magazine The New Masses spread unfounded rumors of up to 42 deaths. The Empire State Building cost $40,948,900 to build, including demolition of the Waldorf–Astoria (equivalent to $554,644,100 in 2018). This was lower than the $60 million budgeted for construction.

Lewis Hine captured many photographs of the construction, documenting not only the work itself but also providing insight into the daily life of workers in that era. Hine's images were used extensively by the media to publish daily press releases. According to the writer Jim Rasenberger, Hine "climbed out onto the steel with the ironworkers and dangled from a derrick cable hundreds of feet above the city to capture, as no one ever had before (or has since), the dizzy work of building skyscrapers". In Rasenberger's words, Hine turned what might have been an assignment of "corporate flak" into "exhilarating art". These images were later organized into their own collection. Onlookers were enraptured by the sheer height at which the steelworkers operated. New York magazine wrote of the steelworkers: "Like little spiders they toiled, spinning a fabric of steel against the sky".

Opening and early years