Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

August 6, 2019

Bottom line is, executions have never been "humane", despite advancements in technology. The death penalty should be abolished as all methods have proven to be cruel and unusual.

129 Years Ago Today; The War of Currents takes a disturbing turn (GRAPHIC descriptions)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electric_chair

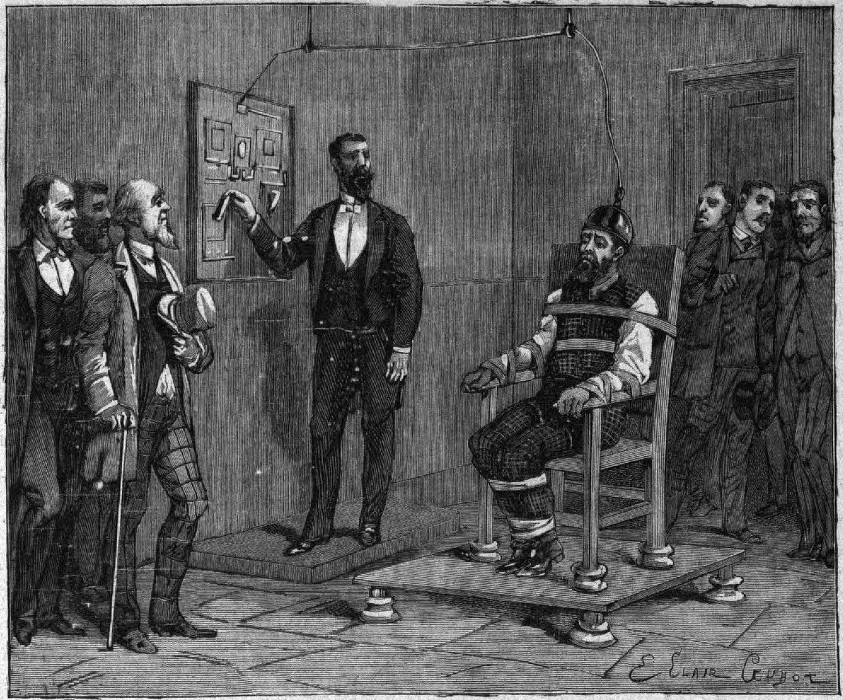

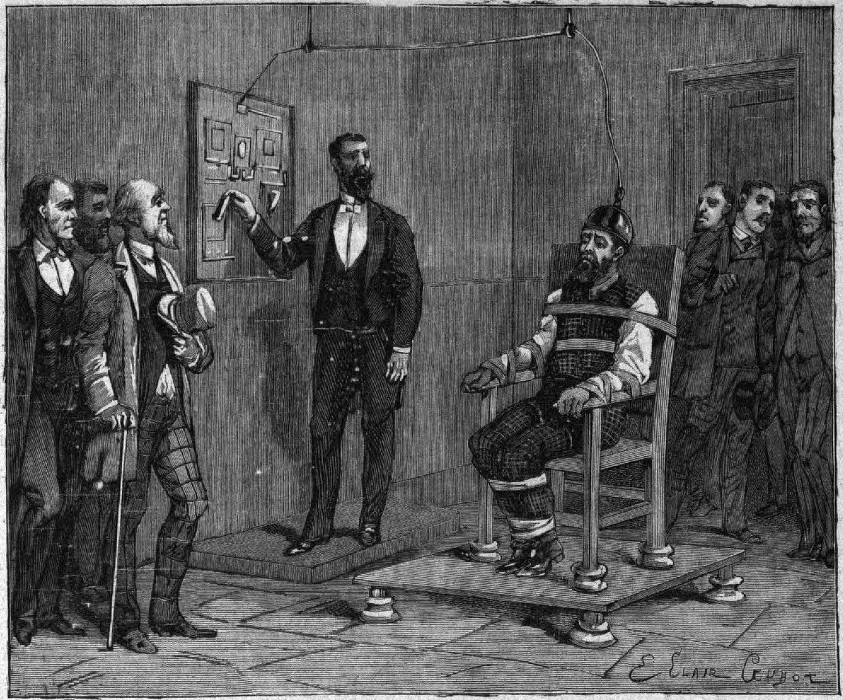

The execution of William Kemmler, August 6, 1890

Execution by electrocution, performed using an electric chair, is a method of execution originating in the United States in which the condemned person is strapped to a specially built wooden chair and electrocuted through electrodes fastened on the head and leg. This execution method, conceived in 1881 by a Buffalo, New York, dentist named Alfred P. Southwick, was developed throughout the 1880s as a "humane alternative" to hanging, and first used in 1890. This execution method has been used in the United States and for a period of several decades, in the Philippines. While death was originally theorized to result from damage to the brain, it was eventually shown in 1899 that it primarily results from ventricular fibrillation and eventual cardiac arrest.

Once the person was attached to the chair, various cycles (differing in voltage and duration) of alternating current would be passed through the individual's body in order to cause fatal damage to the internal organs. The first, more powerful jolt of electric current is intended to cause immediate unconsciousness, ventricular fibrillation, and eventual cardiac arrest. The second, less powerful jolt is intended to cause fatal damage to the vital organs.

Although the electric chair has long been a symbol of the death penalty in the United States, its use is in decline due to the rise of lethal injection, which is widely believed to be a more humane method of execution. While some states still maintain electrocution as a method of execution, today it is only maintained as a secondary method that may be chosen over lethal injection at the request of the prisoner, except in Tennessee, where it may be used without input from the prisoner if the drugs for lethal injection are not available. As of 2014, electrocution is an optional form of execution in the states of Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, and Virginia, all of which allow the prisoner to choose lethal injection as an alternative method. In the state of Kentucky, the electric chair has been retired, except for those whose capital crimes were committed prior to March 31, 1998, and who choose electrocution; inmates who do not choose electrocution and inmates who committed their crimes after the designated date are executed by lethal injection. Electrocution is also authorized in Kentucky in the event that lethal injection is found unconstitutional by a court. The electric chair is an alternate form of execution approved for potential use in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma if other forms of execution are found unconstitutional in the state at the time of execution.

On February 8, 2008, the Nebraska Supreme Court determined that execution by electric chair was a "cruel and unusual punishment" under the state's constitution. This brought executions of this type to an end in Nebraska, the only remaining state to retain electrocution as its sole method of execution.

Invention

In the late 1870s to early 1880s, the spread of arc lighting, a type of brilliant outdoor street lighting that required high voltages in the range of 3000–6000 volts, was followed by one story after another in newspapers about how the high voltages used were killing people, usually unwary linemen, a strange new phenomenon that seemed to instantaneously strike a victim dead without leaving a mark. One of these accidents, in Buffalo, New York, on August 7, 1881, led to the inception of the electric chair. That evening a drunken dock worker, looking for the thrill of a tingling sensation he had noticed before, managed to sneak his way into a Brush Electric Company arc lighting power house and grabbed the brush and ground of a large electric dynamo. He died instantly. The coroner who investigated the case brought it up at a local Buffalo scientific society. Another member, Alfred P. Southwick, a dentist who had a technical background, thought some application could be found for the curious phenomenon.

Southwick, local physician George E. Fell, and the head of the Buffalo ASPCA performed a series of experiments electrocuting hundreds of stray dogs, experimenting with animals in water, out of water, electrode types and placement, and conductive material until they came up with a repeatable method to euthanize animals using electricity. Southwick went on in the early 1880s to advocate that this method be used as a more humane replacement for hanging in capital cases, coming to national attention when he published his ideas in scientific journals in 1882 and 1883. He worked out calculations based on the dog experiments, trying to develop a scaled-up method that would work on humans. Early on in his designs he adopted a modified version of the dental chair as a way to restrain the condemned, a device that from then on would be called the electric chair.

The Gerry Commission

After a series of botched hangings in the United States, there was mounting criticism of that form of capital punishment and the death penalty in general. In 1886, newly elected New York State governor David B. Hill set up a three-member death penalty commission, which was chaired by the human rights advocate and reformer Elbridge Thomas Gerry and included New York lawyer and politician Matthew Hale and Southwick, to investigate a more humane means of execution.

The commission members surveyed the history of execution and sent out a fact-finding questionnaire to government officials, lawyers, and medical experts all around the state asking for their opinion. A slight majority of respondents recommended hanging over electrocution, with a few instead recommending the abolition of capital punishment. The commission also contacted electrical experts, including Thomson-Houston Electric Company's Elihu Thomson (who recommended high voltage AC connected to the head and the spine) and the inventor Thomas Edison (who also recommended AC, as well as using a Westinghouse generator). They also attended electrocutions of dogs by George Fell who had worked with Southwick in the early 1880s experiments. Fell was conducting further experiments, electrocuting anesthetized dissected dogs trying to discern exactly how electricity killed a subject.

In 1888, the Commission recommended electrocution using Southwick's electric chair idea with metal conductors attached to the condemned person's head and feet. They further recommended that executions be handled by the state instead of the individual counties with three electric chairs set up at Auburn, Clinton, and Sing Sing prisons. A bill following these recommendations passed the legislature and was signed by Governor Hill on June 4, 1888, set to go into effect on January 1, 1889.

The Medico-Legal commission

The bill itself contained no details on the type or amount of electricity that should be used and the New York Medico-Legal Society, an informal society composed of doctors and lawyers, was given the task of determining these factors. In September 1888, a committee was formed and recommended 3000 volts, although the type of electricity, direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC), was not determined, and since tests up to that point had been done on animals smaller than a human (dogs), some members were unsure that the lethality of AC had been conclusively proven.

At this point the state's efforts to design the electric chair became intermixed with what has become to be known as the War of Currents, a competition between Thomas Edison's direct current power system and George Westinghouse's alternating current based system. The two companies had been competing commercially since 1886 and a series of events had turned it into an all-out media war in 1888. The committee head, neurologist Frederick Peterson, enlisted the services of Harold P. Brown as a consultant. Brown had been on his own crusade against alternating current after the shoddy installation of pole-mounted AC arc lighting lines in New York City had caused several deaths in early 1888. Peterson had been an assistant at Brown's July 1888 public electrocution of dogs with AC at Columbia College, an attempt by Brown to prove AC was more deadly than DC. Technical assistance in these demonstrations was provided by Thomas Edison's West Orange laboratory and there grew to be some form of collusion between Edison Electric and Brown. Back at West Orange on December 5, 1888 Brown set up an experiment with members of the press, members of the Medico-Legal Society including Elbridge Gerry who was also chairman of the death penalty commission, and Thomas Edison looking on. Brown used alternating current for all of his tests on animals larger than a human, including 4 calves and a lame horse, all dispatched with 750 volts of AC. Based on these results the Medico-Legal Society recommended the use of 1000–1500 volts of alternating current for executions and newspapers noted the AC used was half the voltage used in the power lines over the streets of American cities. Westinghouse criticized these test as a skewed self-serving demonstration designed to be a direct attack on alternating current and accused Brown of being in the employ of Edison.

At the request of death penalty commission chairman Gerry, Medico-Legal Society members; electrotherapy expert Alphonse David Rockwell, Carlos Frederick MacDonald, and Columbia College professor Louis H. Laudy, were given the task of working out the details of electrode placement. They again turned to Brown to supply the technical assistance. Brown asked Edison Electric Light to supply equipment for the tests and treasurer Francis S. Hastings (who seemed to be one of the primary movers at the company trying to portray Westinghouse as a peddler of death dealing AC current) tried to obtain a Westinghouse AC generator for the test but found none could be acquired. They ended up using Edison's West Orange laboratory for the animal tests they conducted in mid-March 1889. Superintendent of Prisons Austin E. Lathrop asked Brown to design the chair, but Brown turned down the offer. Dr. George Fell drew up the final designs for a simple oak chair and went against the Medico-Legal Society recommendations, changing the position of the electrodes to the head and the middle of the back. Brown did take on the job of finding the generators needed to power the chair. He managed to surreptitiously acquire three Westinghouse AC generators that were being decommissioned with the help of Edison and Westinghouse's chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, a move that made sure that Westinghouse's equipment would be associated with the first execution. The electric chair was built by Edwin F. Davis, the first "state electrician" (executioner) for the State of New York.

First execution

The first person in line to die under New York's new electrocution law was Joseph Chappleau, convicted for beating his neighbor to death with a sled stake, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The next person scheduled to be executed was William Kemmler, convicted of murdering his wife with a hatchet. An appeal on Kemmler's behalf was made to the New York Court of Appeals on the grounds that use of electricity as a means of execution constituted a "cruel and unusual punishment" and was thus contrary to the constitutions of the United States and the state of New York. On December 30, 1889, the writ of habeas corpus sworn out on Kemmler's behalf was denied by the court, with Judge Dwight writing in a lengthy ruling:

We have no doubt that if the Legislature of this State should undertake to proscribe for any offense against its laws the punishment of burning at the stake, breaking at the wheel, etc., it would be the duty of the courts to pronounce upon such attempt the condemnation of the Constitution. The question now to be answered is whether the legislative act here assailed is subject to the same condemnation. Certainly, it is not so on its face, for, although the mode of death described is conceded to be unusual, there is no common knowledge or consent that it is cruel; it is a question of fact whether an electric current of sufficient intensity and skillfully applied will produce death without unnecessary suffering.

Kemmler was executed in New York's Auburn Prison on August 6, 1890; the "state electrician" was Edwin F. Davis. The first 17-second passage of 1,000 volts AC of current through Kemmler caused unconsciousness, but failed to stop his heart and breathing. The attending physicians, Edward Charles Spitzka and Carlos F. MacDonald, came forward to examine Kemmler. After confirming Kemmler was still alive, Spitzka reportedly called out, "Have the current turned on again, quick, no delay." The generator needed time to re-charge, however. In the second attempt, Kemmler received a 2,000 volt AC shock. Blood vessels under the skin ruptured and bled, and the areas around the electrodes singed. The entire execution took about eight minutes. George Westinghouse later commented that, "They would have done better using an axe", and a witnessing reporter claimed that it was "an awful spectacle, far worse than hanging".

</snip>

The execution of William Kemmler, August 6, 1890

Execution by electrocution, performed using an electric chair, is a method of execution originating in the United States in which the condemned person is strapped to a specially built wooden chair and electrocuted through electrodes fastened on the head and leg. This execution method, conceived in 1881 by a Buffalo, New York, dentist named Alfred P. Southwick, was developed throughout the 1880s as a "humane alternative" to hanging, and first used in 1890. This execution method has been used in the United States and for a period of several decades, in the Philippines. While death was originally theorized to result from damage to the brain, it was eventually shown in 1899 that it primarily results from ventricular fibrillation and eventual cardiac arrest.

Once the person was attached to the chair, various cycles (differing in voltage and duration) of alternating current would be passed through the individual's body in order to cause fatal damage to the internal organs. The first, more powerful jolt of electric current is intended to cause immediate unconsciousness, ventricular fibrillation, and eventual cardiac arrest. The second, less powerful jolt is intended to cause fatal damage to the vital organs.

Although the electric chair has long been a symbol of the death penalty in the United States, its use is in decline due to the rise of lethal injection, which is widely believed to be a more humane method of execution. While some states still maintain electrocution as a method of execution, today it is only maintained as a secondary method that may be chosen over lethal injection at the request of the prisoner, except in Tennessee, where it may be used without input from the prisoner if the drugs for lethal injection are not available. As of 2014, electrocution is an optional form of execution in the states of Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, and Virginia, all of which allow the prisoner to choose lethal injection as an alternative method. In the state of Kentucky, the electric chair has been retired, except for those whose capital crimes were committed prior to March 31, 1998, and who choose electrocution; inmates who do not choose electrocution and inmates who committed their crimes after the designated date are executed by lethal injection. Electrocution is also authorized in Kentucky in the event that lethal injection is found unconstitutional by a court. The electric chair is an alternate form of execution approved for potential use in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma if other forms of execution are found unconstitutional in the state at the time of execution.

On February 8, 2008, the Nebraska Supreme Court determined that execution by electric chair was a "cruel and unusual punishment" under the state's constitution. This brought executions of this type to an end in Nebraska, the only remaining state to retain electrocution as its sole method of execution.

Invention

In the late 1870s to early 1880s, the spread of arc lighting, a type of brilliant outdoor street lighting that required high voltages in the range of 3000–6000 volts, was followed by one story after another in newspapers about how the high voltages used were killing people, usually unwary linemen, a strange new phenomenon that seemed to instantaneously strike a victim dead without leaving a mark. One of these accidents, in Buffalo, New York, on August 7, 1881, led to the inception of the electric chair. That evening a drunken dock worker, looking for the thrill of a tingling sensation he had noticed before, managed to sneak his way into a Brush Electric Company arc lighting power house and grabbed the brush and ground of a large electric dynamo. He died instantly. The coroner who investigated the case brought it up at a local Buffalo scientific society. Another member, Alfred P. Southwick, a dentist who had a technical background, thought some application could be found for the curious phenomenon.

Southwick, local physician George E. Fell, and the head of the Buffalo ASPCA performed a series of experiments electrocuting hundreds of stray dogs, experimenting with animals in water, out of water, electrode types and placement, and conductive material until they came up with a repeatable method to euthanize animals using electricity. Southwick went on in the early 1880s to advocate that this method be used as a more humane replacement for hanging in capital cases, coming to national attention when he published his ideas in scientific journals in 1882 and 1883. He worked out calculations based on the dog experiments, trying to develop a scaled-up method that would work on humans. Early on in his designs he adopted a modified version of the dental chair as a way to restrain the condemned, a device that from then on would be called the electric chair.

The Gerry Commission

After a series of botched hangings in the United States, there was mounting criticism of that form of capital punishment and the death penalty in general. In 1886, newly elected New York State governor David B. Hill set up a three-member death penalty commission, which was chaired by the human rights advocate and reformer Elbridge Thomas Gerry and included New York lawyer and politician Matthew Hale and Southwick, to investigate a more humane means of execution.

The commission members surveyed the history of execution and sent out a fact-finding questionnaire to government officials, lawyers, and medical experts all around the state asking for their opinion. A slight majority of respondents recommended hanging over electrocution, with a few instead recommending the abolition of capital punishment. The commission also contacted electrical experts, including Thomson-Houston Electric Company's Elihu Thomson (who recommended high voltage AC connected to the head and the spine) and the inventor Thomas Edison (who also recommended AC, as well as using a Westinghouse generator). They also attended electrocutions of dogs by George Fell who had worked with Southwick in the early 1880s experiments. Fell was conducting further experiments, electrocuting anesthetized dissected dogs trying to discern exactly how electricity killed a subject.

In 1888, the Commission recommended electrocution using Southwick's electric chair idea with metal conductors attached to the condemned person's head and feet. They further recommended that executions be handled by the state instead of the individual counties with three electric chairs set up at Auburn, Clinton, and Sing Sing prisons. A bill following these recommendations passed the legislature and was signed by Governor Hill on June 4, 1888, set to go into effect on January 1, 1889.

The Medico-Legal commission

The bill itself contained no details on the type or amount of electricity that should be used and the New York Medico-Legal Society, an informal society composed of doctors and lawyers, was given the task of determining these factors. In September 1888, a committee was formed and recommended 3000 volts, although the type of electricity, direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC), was not determined, and since tests up to that point had been done on animals smaller than a human (dogs), some members were unsure that the lethality of AC had been conclusively proven.

At this point the state's efforts to design the electric chair became intermixed with what has become to be known as the War of Currents, a competition between Thomas Edison's direct current power system and George Westinghouse's alternating current based system. The two companies had been competing commercially since 1886 and a series of events had turned it into an all-out media war in 1888. The committee head, neurologist Frederick Peterson, enlisted the services of Harold P. Brown as a consultant. Brown had been on his own crusade against alternating current after the shoddy installation of pole-mounted AC arc lighting lines in New York City had caused several deaths in early 1888. Peterson had been an assistant at Brown's July 1888 public electrocution of dogs with AC at Columbia College, an attempt by Brown to prove AC was more deadly than DC. Technical assistance in these demonstrations was provided by Thomas Edison's West Orange laboratory and there grew to be some form of collusion between Edison Electric and Brown. Back at West Orange on December 5, 1888 Brown set up an experiment with members of the press, members of the Medico-Legal Society including Elbridge Gerry who was also chairman of the death penalty commission, and Thomas Edison looking on. Brown used alternating current for all of his tests on animals larger than a human, including 4 calves and a lame horse, all dispatched with 750 volts of AC. Based on these results the Medico-Legal Society recommended the use of 1000–1500 volts of alternating current for executions and newspapers noted the AC used was half the voltage used in the power lines over the streets of American cities. Westinghouse criticized these test as a skewed self-serving demonstration designed to be a direct attack on alternating current and accused Brown of being in the employ of Edison.

At the request of death penalty commission chairman Gerry, Medico-Legal Society members; electrotherapy expert Alphonse David Rockwell, Carlos Frederick MacDonald, and Columbia College professor Louis H. Laudy, were given the task of working out the details of electrode placement. They again turned to Brown to supply the technical assistance. Brown asked Edison Electric Light to supply equipment for the tests and treasurer Francis S. Hastings (who seemed to be one of the primary movers at the company trying to portray Westinghouse as a peddler of death dealing AC current) tried to obtain a Westinghouse AC generator for the test but found none could be acquired. They ended up using Edison's West Orange laboratory for the animal tests they conducted in mid-March 1889. Superintendent of Prisons Austin E. Lathrop asked Brown to design the chair, but Brown turned down the offer. Dr. George Fell drew up the final designs for a simple oak chair and went against the Medico-Legal Society recommendations, changing the position of the electrodes to the head and the middle of the back. Brown did take on the job of finding the generators needed to power the chair. He managed to surreptitiously acquire three Westinghouse AC generators that were being decommissioned with the help of Edison and Westinghouse's chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, a move that made sure that Westinghouse's equipment would be associated with the first execution. The electric chair was built by Edwin F. Davis, the first "state electrician" (executioner) for the State of New York.

First execution

The first person in line to die under New York's new electrocution law was Joseph Chappleau, convicted for beating his neighbor to death with a sled stake, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The next person scheduled to be executed was William Kemmler, convicted of murdering his wife with a hatchet. An appeal on Kemmler's behalf was made to the New York Court of Appeals on the grounds that use of electricity as a means of execution constituted a "cruel and unusual punishment" and was thus contrary to the constitutions of the United States and the state of New York. On December 30, 1889, the writ of habeas corpus sworn out on Kemmler's behalf was denied by the court, with Judge Dwight writing in a lengthy ruling:

We have no doubt that if the Legislature of this State should undertake to proscribe for any offense against its laws the punishment of burning at the stake, breaking at the wheel, etc., it would be the duty of the courts to pronounce upon such attempt the condemnation of the Constitution. The question now to be answered is whether the legislative act here assailed is subject to the same condemnation. Certainly, it is not so on its face, for, although the mode of death described is conceded to be unusual, there is no common knowledge or consent that it is cruel; it is a question of fact whether an electric current of sufficient intensity and skillfully applied will produce death without unnecessary suffering.

Kemmler was executed in New York's Auburn Prison on August 6, 1890; the "state electrician" was Edwin F. Davis. The first 17-second passage of 1,000 volts AC of current through Kemmler caused unconsciousness, but failed to stop his heart and breathing. The attending physicians, Edward Charles Spitzka and Carlos F. MacDonald, came forward to examine Kemmler. After confirming Kemmler was still alive, Spitzka reportedly called out, "Have the current turned on again, quick, no delay." The generator needed time to re-charge, however. In the second attempt, Kemmler received a 2,000 volt AC shock. Blood vessels under the skin ruptured and bled, and the areas around the electrodes singed. The entire execution took about eight minutes. George Westinghouse later commented that, "They would have done better using an axe", and a witnessing reporter claimed that it was "an awful spectacle, far worse than hanging".

</snip>

Bottom line is, executions have never been "humane", despite advancements in technology. The death penalty should be abolished as all methods have proven to be cruel and unusual.

August 5, 2019

Bonus material:

131 Years Ago Today; Bertha Benz makes the first automobile "road trip"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bertha_Benz

Bertha Ringer, circa 1871, as she became Karl Benz's business partner

Bertha Benz, born Bertha Ringer, 3 May 1849 – 5 May 1944) was a German automotive pioneer. She was the business partner and wife of automobile inventor Karl Benz. On 5 August 1888, she was the first person to drive an automobile over a long distance, rigorously field testing the patent Motorwagen, inventing brake pads and solving several engineering issues during the 65 mile trip. In doing so, she brought the Benz Patent-Motorwagen worldwide attention and got the company its first sales.

<snip>

The Patent Motor Car

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen Number 3 of 1886, used by Bertha Benz for the highly publicized first long distance road trip, 106 km (66 mi), by automobile

In 1886, Benz presented the Patent-Motorwagen automobile to the world. Within the decade, 25 vehicles had been built. With cutting-edge bicycle constructions, the Model I was the original Patent Motor Car and the world's first automobile.

The Model II was converted to a four-wheeler for test purposes, making it the only one of this model.

The first Patent Motor Car sold in small production runs was the Model III. It had powered rear wheels with a ringed steel and solid rubber, steerable front wheel. Various options from which to choose were provided for customers, such as seat arrangements and a folding top.

First cross-country automobile journey

On 5 August 1888, 39-year-old Bertha Benz drove from Mannheim to Pforzheim with her sons Richard and Eugen, thirteen and fifteen years old respectively, in a Model III, without telling her husband and without permission of the authorities, thus becoming the first person to drive an automobile a significant distance, though illegally. Before this historic trip, motorized drives were merely very short trials, returning to the point of origin, made with assistance of mechanics. Following wagon tracks, this pioneering tour covered a one-way distance of about 106 km (66 mi).

Although the ostensible purpose of the trip was to visit her mother, Bertha Benz had other motives — to prove to her husband, who had failed to adequately consider marketing his invention, that the automobile in which they both had heavily invested would become a financial success once it was shown to be useful to the general public; and to give her husband the confidence that his constructions had a future.

She left Mannheim around dawn, solving numerous problems along the way. Bertha demonstrated her significant technical capabilities on this journey. With no fuel tank and only a 4.5-litre supply of petrol in the carburetor, she had to find ligroin, the petroleum solvent needed for the car to run. It was only available at apothecary shops, so she stopped in Wiesloch at the city pharmacy to purchase the fuel. At the time, petrol and other fuels could only be bought from chemists, and so this is how the chemist in Wiesloch became the first fuel station in the world.

She cleaned a blocked fuel line with her hat pin and used her garter as insulation material. A blacksmith had to help mend a chain at one point. When the wooden brakes began to fail, Benz visited a cobbler to install leather, making the world's first pair of brake pads. An evaporative cooling system was employed to cool the engine, making water supply a big worry along the trip. The trio added water to their supply every time they stopped. The car's two gears were not enough to surmount uphill inclines and Eugen and Richard often had to push the vehicle up steep roads. Benz reached Pforzheim somewhat after dusk, notifying her husband of her successful journey by telegram. She drove back to Mannheim several days later.

The novel trip received a great deal of publicity, as she had sought. The drive was a key event in the technical development of the automobile. The pioneering couple introduced several improvements after Bertha's experiences. She reported everything that had happened along the way and made important suggestions, such as the introduction of an additional gear for climbing hills and brake linings to improve brake-power. Her trip proved to the burgeoning automotive industry that test drives were essential to their business.

Karl and Bertha Benz 1925

</snip>

Bertha Ringer, circa 1871, as she became Karl Benz's business partner

Bertha Benz, born Bertha Ringer, 3 May 1849 – 5 May 1944) was a German automotive pioneer. She was the business partner and wife of automobile inventor Karl Benz. On 5 August 1888, she was the first person to drive an automobile over a long distance, rigorously field testing the patent Motorwagen, inventing brake pads and solving several engineering issues during the 65 mile trip. In doing so, she brought the Benz Patent-Motorwagen worldwide attention and got the company its first sales.

<snip>

The Patent Motor Car

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen Number 3 of 1886, used by Bertha Benz for the highly publicized first long distance road trip, 106 km (66 mi), by automobile

In 1886, Benz presented the Patent-Motorwagen automobile to the world. Within the decade, 25 vehicles had been built. With cutting-edge bicycle constructions, the Model I was the original Patent Motor Car and the world's first automobile.

The Model II was converted to a four-wheeler for test purposes, making it the only one of this model.

The first Patent Motor Car sold in small production runs was the Model III. It had powered rear wheels with a ringed steel and solid rubber, steerable front wheel. Various options from which to choose were provided for customers, such as seat arrangements and a folding top.

First cross-country automobile journey

On 5 August 1888, 39-year-old Bertha Benz drove from Mannheim to Pforzheim with her sons Richard and Eugen, thirteen and fifteen years old respectively, in a Model III, without telling her husband and without permission of the authorities, thus becoming the first person to drive an automobile a significant distance, though illegally. Before this historic trip, motorized drives were merely very short trials, returning to the point of origin, made with assistance of mechanics. Following wagon tracks, this pioneering tour covered a one-way distance of about 106 km (66 mi).

Although the ostensible purpose of the trip was to visit her mother, Bertha Benz had other motives — to prove to her husband, who had failed to adequately consider marketing his invention, that the automobile in which they both had heavily invested would become a financial success once it was shown to be useful to the general public; and to give her husband the confidence that his constructions had a future.

She left Mannheim around dawn, solving numerous problems along the way. Bertha demonstrated her significant technical capabilities on this journey. With no fuel tank and only a 4.5-litre supply of petrol in the carburetor, she had to find ligroin, the petroleum solvent needed for the car to run. It was only available at apothecary shops, so she stopped in Wiesloch at the city pharmacy to purchase the fuel. At the time, petrol and other fuels could only be bought from chemists, and so this is how the chemist in Wiesloch became the first fuel station in the world.

She cleaned a blocked fuel line with her hat pin and used her garter as insulation material. A blacksmith had to help mend a chain at one point. When the wooden brakes began to fail, Benz visited a cobbler to install leather, making the world's first pair of brake pads. An evaporative cooling system was employed to cool the engine, making water supply a big worry along the trip. The trio added water to their supply every time they stopped. The car's two gears were not enough to surmount uphill inclines and Eugen and Richard often had to push the vehicle up steep roads. Benz reached Pforzheim somewhat after dusk, notifying her husband of her successful journey by telegram. She drove back to Mannheim several days later.

The novel trip received a great deal of publicity, as she had sought. The drive was a key event in the technical development of the automobile. The pioneering couple introduced several improvements after Bertha's experiences. She reported everything that had happened along the way and made important suggestions, such as the introduction of an additional gear for climbing hills and brake linings to improve brake-power. Her trip proved to the burgeoning automotive industry that test drives were essential to their business.

Karl and Bertha Benz 1925

</snip>

Bonus material:

August 5, 2019

A big win for the concept of "Freedom of the Press", several decades before the Bill of Rights was penned.

284 Years Ago Today; John Peter Zenger acquitted of Seditious Libel against Royal NY Governor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Peter_Zenger

The trial, as imagined by an illustrator in the 1883 book Wall Street in History

John Peter Zenger (October 26, 1697 – July 28, 1746) was an American printer and journalist in New York City. Zenger printed The New York Weekly Journal. He was accused of libel in 1734 by William Cosby, the royal governor of New York, but the jury acquitted Zenger, who became a symbol for freedom of the press.

In 1733, Zenger began printing The New York Weekly Journal, in which the journal voiced opinions critical of the colonial governor, William Cosby. On November 17, 1734, on Cosby's orders, the sheriff arrested Zenger. After a grand jury refused to indict him, the Attorney General Richard Bradley charged him with libel in August 1735.

Zenger's lawyers, Andrew Hamilton and William Smith, Sr., successfully argued that truth is a defense against charges of libel.

Libel case

A page from Zenger's New-York Weekly Journal, 7 January 1733

In 1733, Zenger printed copies of newspapers in New York to voice his disagreement with the actions of newly appointed colonial governor William Cosby. On his arrival in New York City, Cosby had plunged into a rancorous quarrel with the council of the colony over his salary. Unable to control the colony's supreme court, he removed Chief Justice Lewis Morris, replacing him with James DeLancey of the Royal Party. Supported by members of the Popular Party, Zenger's New-York Weekly Journal continued to publish articles critical of the royal governor. Finally, Cosby issued a proclamation condemning the newspaper's "divers scandalous, virulent, false and seditious reflections."

Zenger was charged with libel. James Alexander was Zenger's first counsel, but the court found him in contempt and removed him from the case. After more than eight months in prison, Zenger went to trial, defended by the Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton and the New York lawyer William Smith, Sr. The case was now a cause célèbre, with public interest at fever-pitch. Rebuffed repeatedly by chief justice James DeLancey during the trial, Hamilton decided to plead his client's case directly to the jury. After the lawyers for both sides finished their arguments, the jury retired, only to return in ten minutes with a verdict of not guilty.

In defending Zenger in this landmark case, Hamilton and Smith attempted to establish the precedent that a statement, even if defamatory, is not libelous if it can be proved, thus affirming freedom of the press in America; however, succeeding royal governors clamped down on freedom of the press until the American Revolution. This case is the groundwork of freedom of the press, not its legal precedent. As late as 1804, the journalist Harry Croswell lost a series of prosecutions and appeals, because truth was not a defense against libel, as decided by the New York Supreme Court in People v. Croswell. It was only the following year that the assembly, reacting to this verdict, passed a law that allowed truth as a defense against a charge of libel.

"Cato" article

In an issue of The New York Weekly Journal prior to Zenger's arrest, is a typical attack against the government in Zenger's newspaper. In an issue dated February 25, 1733 is an opinion piece written under the pseudonym "Cato." This was a pen-name used by British writers John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, whose essays were published as Cato's Letters (1723). Jeffery A. Smith writes that "Cato" was "The leading luminary of the 18th century libertarian press theory...Editions of Cato's Letters were published and republished for decades in Britain and were immensely popular in America." This article gave its readers a preview of the same argument attorneys Hamilton and Smith presented 18 months later in the government's libel case against Zenger — that truth is an absolute defense against libel. The words are reprinted from Cato's essay "Reflections Upon Libelling":

</snip>

The trial, as imagined by an illustrator in the 1883 book Wall Street in History

John Peter Zenger (October 26, 1697 – July 28, 1746) was an American printer and journalist in New York City. Zenger printed The New York Weekly Journal. He was accused of libel in 1734 by William Cosby, the royal governor of New York, but the jury acquitted Zenger, who became a symbol for freedom of the press.

In 1733, Zenger began printing The New York Weekly Journal, in which the journal voiced opinions critical of the colonial governor, William Cosby. On November 17, 1734, on Cosby's orders, the sheriff arrested Zenger. After a grand jury refused to indict him, the Attorney General Richard Bradley charged him with libel in August 1735.

Zenger's lawyers, Andrew Hamilton and William Smith, Sr., successfully argued that truth is a defense against charges of libel.

Libel case

A page from Zenger's New-York Weekly Journal, 7 January 1733

In 1733, Zenger printed copies of newspapers in New York to voice his disagreement with the actions of newly appointed colonial governor William Cosby. On his arrival in New York City, Cosby had plunged into a rancorous quarrel with the council of the colony over his salary. Unable to control the colony's supreme court, he removed Chief Justice Lewis Morris, replacing him with James DeLancey of the Royal Party. Supported by members of the Popular Party, Zenger's New-York Weekly Journal continued to publish articles critical of the royal governor. Finally, Cosby issued a proclamation condemning the newspaper's "divers scandalous, virulent, false and seditious reflections."

Zenger was charged with libel. James Alexander was Zenger's first counsel, but the court found him in contempt and removed him from the case. After more than eight months in prison, Zenger went to trial, defended by the Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton and the New York lawyer William Smith, Sr. The case was now a cause célèbre, with public interest at fever-pitch. Rebuffed repeatedly by chief justice James DeLancey during the trial, Hamilton decided to plead his client's case directly to the jury. After the lawyers for both sides finished their arguments, the jury retired, only to return in ten minutes with a verdict of not guilty.

In defending Zenger in this landmark case, Hamilton and Smith attempted to establish the precedent that a statement, even if defamatory, is not libelous if it can be proved, thus affirming freedom of the press in America; however, succeeding royal governors clamped down on freedom of the press until the American Revolution. This case is the groundwork of freedom of the press, not its legal precedent. As late as 1804, the journalist Harry Croswell lost a series of prosecutions and appeals, because truth was not a defense against libel, as decided by the New York Supreme Court in People v. Croswell. It was only the following year that the assembly, reacting to this verdict, passed a law that allowed truth as a defense against a charge of libel.

"Cato" article

In an issue of The New York Weekly Journal prior to Zenger's arrest, is a typical attack against the government in Zenger's newspaper. In an issue dated February 25, 1733 is an opinion piece written under the pseudonym "Cato." This was a pen-name used by British writers John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, whose essays were published as Cato's Letters (1723). Jeffery A. Smith writes that "Cato" was "The leading luminary of the 18th century libertarian press theory...Editions of Cato's Letters were published and republished for decades in Britain and were immensely popular in America." This article gave its readers a preview of the same argument attorneys Hamilton and Smith presented 18 months later in the government's libel case against Zenger — that truth is an absolute defense against libel. The words are reprinted from Cato's essay "Reflections Upon Libelling":

A libel is not less the libel for being true...But this doctrine only holds true as to private and personal failings; and it is quite otherwise when the crimes of men come to affect the publick…Machiavel says, Calumny is pernicious, but accusation beneficial, to a state; and he shews instances where states have suffered or perished for not having, or for neglecting, the power to accuse great men who were criminals, or thought to be so…surely it cannot be more pernicious to calumniate even good men, than not to be able to accuse ill ones.

</snip>

A big win for the concept of "Freedom of the Press", several decades before the Bill of Rights was penned.

August 4, 2019

MSNBC breaking - Dayton shooter Connor Betts's sister and boyfriend found dead in car near scene

LO found them dead in a car nearby - Looking for links

..on edit. Jeremy's spoken. ![]()

![]()

August 3, 2019

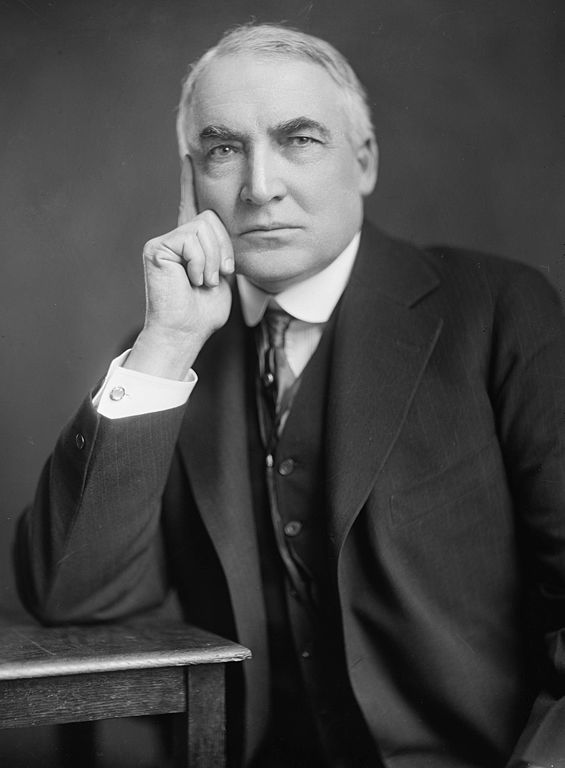

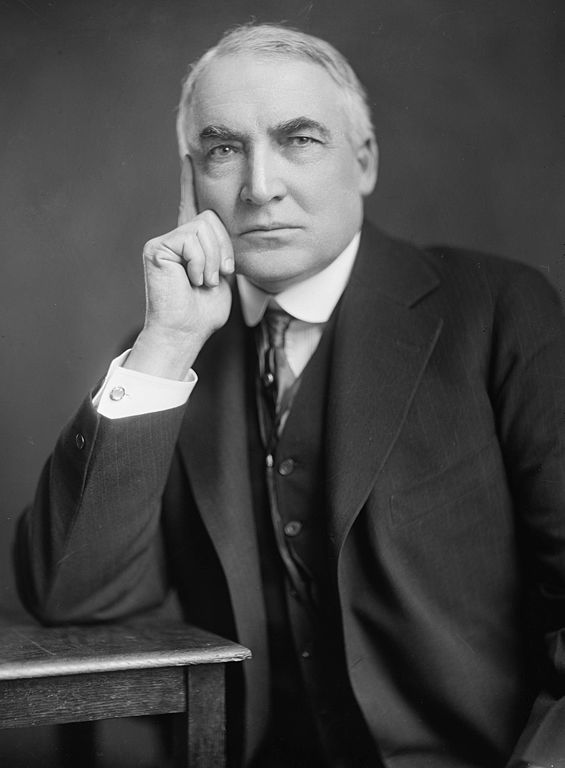

There's an interactive graph further down in the article. Here's a snip of the Top 10 POTUSes, sorted by the last quoted poll, the 2018 Siena College poll:

...and the bottom 10:

Historical rankings of presidents of the United States (Wikipedia)

A fascinating Wikipedia article to peruse on a lazy Saturday morning...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_rankings_of_presidents_of_the_United_States

In political studies, surveys have been conducted in order to construct historical rankings of the success of individuals who have served as the president of the United States. Ranking systems are usually based on surveys of academic historians and political scientists or popular opinion. The rankings focus on the presidential achievements, leadership qualities, failures and faults.

General findings

Abraham Lincoln, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George Washington are most often listed as the three highest-rated presidents among historians. The remaining places within the Top 10 are often rounded out by Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Harry S Truman, Woodrow Wilson, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Andrew Jackson, and John F. Kennedy. More recent presidents such as Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton are often rated among the greatest in public opinion polls, but do not always rank as highly among presidential scholars and historians. The bottom 10 often include James Buchanan, Warren G. Harding, Andrew Johnson, Franklin Pierce, Millard Fillmore, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Ulysses S. Grant, Zachary Taylor, and George W. Bush. Because William Henry Harrison (30 days) and James A. Garfield (200 days, incapacitated after 119 days) both died shortly after taking office, they are usually omitted from presidential rankings. Furthermore, Zachary Taylor died after serving as president for only 16 months, but he is usually included. In the case of these three, it is not clear if they received low rankings due to their actions as president, or because each was in office for such a limited time that it is not possible to assess them more thoroughly.

Political scientist Walter Dean Burnham noted the "dichotomous or schizoid profiles" of presidents, which can make some hard to classify. Historian Alan Brinkley stated that "there are presidents who could be considered both failures and great or near great (for example, Nixon)". Historian and political scientist James MacGregor Burns observed of Nixon: "How can one evaluate such an idiosyncratic president, so brilliant and so morally lacking?"

Notable scholar surveys

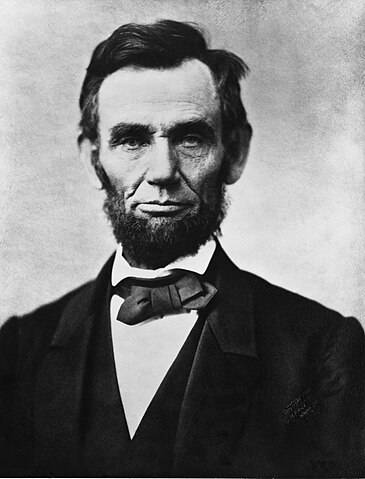

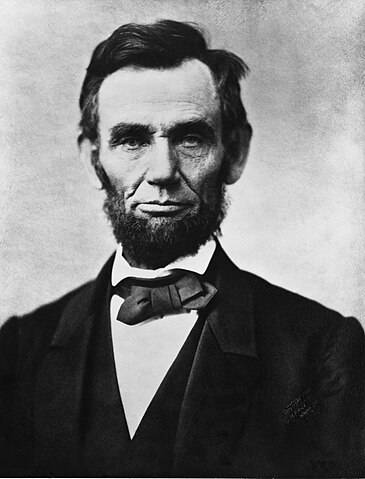

Abraham Lincoln is often considered the greatest president for his leadership during the American Civil War and his eloquence in speeches such as the Gettysburg Address.

James Buchanan is often considered the worst president for his inept leadership during the years leading up to the Civil War.

The 1948 poll was conducted by historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. of Harvard University. The 1962 survey was also conducted by Schlesinger, who surveyed 75 historians.[5] Schlesinger's son, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., conducted another poll in 1996.

The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents also gives the results of the 1982 survey, a poll of 49 historians conducted by the Chicago Tribune. A notable difference from the 1962 Schlesinger poll was the ranking of Dwight D. Eisenhower, which rose from 22nd in 1962 to 9th in 1982.

The Siena Research Institute of Siena College conducted surveys in 1982, 1990, 1994, 2002 and 2010. The 1994 survey placed only two presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, above 80 points and two presidents, Andrew Johnson and Warren G. Harding, below 50 points. The 2010 Siena survey had George W. Bush plummet from the initial 2002 ranking of 23rd down to 39th.

The 1996 column shows the results from a poll conducted from 1988 to 1996 by William J. Ridings Jr. and Stuart B. McIver and published in Rating The Presidents: A Ranking of U.S. Leaders, from the Great and Honorable to the Dishonest and Incompetent. More than 719 people took part in the poll, primarily academic historians and political scientists, although some politicians and celebrities also took part. Participants from every state were included and emphasis was placed upon getting input from female historians and "specialists in African-American studies" as well as a few non-American historians. Poll respondents rated the presidents in five categories (leadership qualities, accomplishments and crisis management, political skill, appointments and character and integrity) and the results were tabulated to create the overall ranking.

A 2000 survey by The Wall Street Journal consisted of an "ideologically balanced group of 132 prominent professors of history, law, and political science". This poll sought to include an equal number of liberals and conservatives in the survey as the editors argued that previous polls were dominated by either one group or the other. According to the editors, this poll included responses from more women, minorities and young professors than the 1996 Schlesinger poll. The editors noted that the results of their poll were "remarkably similar" to the 1996 Schlesinger poll, with the main difference in the 2000 poll being the lower rankings for the 1960s presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and John F. Kennedy and higher ranking of President Ronald Reagan at 8th. Franklin D. Roosevelt still ranked in the top three.

Another presidential poll was conducted by The Wall Street Journal in 2005, with James Lindgren of Northwestern University Law School for the Federalist Society. As in the 2000 survey, the editors sought to balance the opinions of liberals and conservatives, adjusting the results "to give Democratic- and Republican-leaning scholars equal weight". Franklin D. Roosevelt still ranked in the top three, but editor James Taranto noted that Democratic-leaning scholars rated George W. Bush the sixth-worst president of all time while Republican scholars rated him the sixth-best, giving him a split-decision rating of "average".

A 2006 Siena College poll of 744 professors reported the following results:

Thomas Kelly, professor emeritus of American studies at Siena College, said: "President Bush would seem to have small hope for high marks from the current generation of practicing historians and political scientists. In this case, current public opinion polls actually seem to cut the President more slack than the experts do". Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and director of the Siena Research Institute, stated: "In our 2002 presidential rating, with a group of experts comparable to this current poll, President Bush ranked 23rd of 42 presidents. That was shortly after 9/11. Clearly, the professors do not think things have gone well for him in the past few years. These are the experts that teach college students today and will write the history of this era tomorrow".

A 2010 Siena poll of 238 presidential scholars found that former president George W. Bush was ranked 39th out of 43, with poor ratings in handling of the economy, communication, ability to compromise, foreign policy accomplishments and intelligence. Meanwhile, the then-current president Barack Obama was ranked 15th out of 43, with high ratings for imagination, communication ability and intelligence and a low rating for background (family, education and experience).

The C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership consists of rankings from a group of presidential historians and biographers. The C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership has taken place three times: in 2000, 2009 and 2017. The most recent survey was of 91 presidential historians, surveyed by C-SPAN's Academic Advisor Team, made up of Douglas G. Brinkley, Edna Greene Medford and Richard Norton Smith. In the survey, each historian rates each president on a scale of one ("not effective" ) to 10 ("very effective" ) on presidential leadership in ten categories: Public Persuasion, Crisis Leadership, Economic Management, Moral Authority, International Relations, Administrative Skills, Relations with Congress, Vision/Setting An Agenda, Pursued Equal Justice for All and Performance Within the Context of His Times—each category is equally weighed. The results of all three C-SPAN surveys have been fairly consistent. Abraham Lincoln has taken the highest ranking in each survey and George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt have always ranked in the top five while James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson and Franklin Pierce have been ranked at the bottom of all three surveys.

In 2008, The Times daily newspaper of London asked eight of its own "top international and political commentators" to rank all 42 presidents "in order of greatness".

In 2011, through the agency of its United States Presidency Centre (USPC), the Institute for the Study of the Americas (located in the University of London's School of Advanced Study) released the first ever United Kingdom academic survey to rate presidents. This polled the opinion of British specialists in American history and politics to assess presidential performance. They also gave an interim assessment of Barack Obama, but his unfinished presidency was not included in the survey (had he been included, he would have attained eighth place overall).

In 2012, Newsweek magazine asked a panel of historians to rank the ten best presidents since 1900. The results showed that historians had ranked Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama as the best since that year.

A 2013 History News Network poll of 203 American historians, when asked to rate Obama's presidency on an A–F scale, gave him a B- grade. Obama, whom historians graded using 15 separate measures plus an overall grade, was rated most highly in the categories of communication ability, integrity and crisis management; and most poorly for his relationship with Congress, transparency and accountability.

A 2015 poll administered by the American Political Science Association (APSA) among political scientists specializing in the American presidency had Abraham Lincoln in the top spot, with George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Harry S Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, Andrew Jackson and Woodrow Wilson making the top 10. APSA conducted a repeat of this poll in 2018, with Donald Trump appearing for the first time, in last position

</snip>

In political studies, surveys have been conducted in order to construct historical rankings of the success of individuals who have served as the president of the United States. Ranking systems are usually based on surveys of academic historians and political scientists or popular opinion. The rankings focus on the presidential achievements, leadership qualities, failures and faults.

General findings

Abraham Lincoln, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George Washington are most often listed as the three highest-rated presidents among historians. The remaining places within the Top 10 are often rounded out by Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Harry S Truman, Woodrow Wilson, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Andrew Jackson, and John F. Kennedy. More recent presidents such as Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton are often rated among the greatest in public opinion polls, but do not always rank as highly among presidential scholars and historians. The bottom 10 often include James Buchanan, Warren G. Harding, Andrew Johnson, Franklin Pierce, Millard Fillmore, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Ulysses S. Grant, Zachary Taylor, and George W. Bush. Because William Henry Harrison (30 days) and James A. Garfield (200 days, incapacitated after 119 days) both died shortly after taking office, they are usually omitted from presidential rankings. Furthermore, Zachary Taylor died after serving as president for only 16 months, but he is usually included. In the case of these three, it is not clear if they received low rankings due to their actions as president, or because each was in office for such a limited time that it is not possible to assess them more thoroughly.

Political scientist Walter Dean Burnham noted the "dichotomous or schizoid profiles" of presidents, which can make some hard to classify. Historian Alan Brinkley stated that "there are presidents who could be considered both failures and great or near great (for example, Nixon)". Historian and political scientist James MacGregor Burns observed of Nixon: "How can one evaluate such an idiosyncratic president, so brilliant and so morally lacking?"

Notable scholar surveys

Abraham Lincoln is often considered the greatest president for his leadership during the American Civil War and his eloquence in speeches such as the Gettysburg Address.

James Buchanan is often considered the worst president for his inept leadership during the years leading up to the Civil War.

The 1948 poll was conducted by historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. of Harvard University. The 1962 survey was also conducted by Schlesinger, who surveyed 75 historians.[5] Schlesinger's son, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., conducted another poll in 1996.

The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents also gives the results of the 1982 survey, a poll of 49 historians conducted by the Chicago Tribune. A notable difference from the 1962 Schlesinger poll was the ranking of Dwight D. Eisenhower, which rose from 22nd in 1962 to 9th in 1982.

The Siena Research Institute of Siena College conducted surveys in 1982, 1990, 1994, 2002 and 2010. The 1994 survey placed only two presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, above 80 points and two presidents, Andrew Johnson and Warren G. Harding, below 50 points. The 2010 Siena survey had George W. Bush plummet from the initial 2002 ranking of 23rd down to 39th.

The 1996 column shows the results from a poll conducted from 1988 to 1996 by William J. Ridings Jr. and Stuart B. McIver and published in Rating The Presidents: A Ranking of U.S. Leaders, from the Great and Honorable to the Dishonest and Incompetent. More than 719 people took part in the poll, primarily academic historians and political scientists, although some politicians and celebrities also took part. Participants from every state were included and emphasis was placed upon getting input from female historians and "specialists in African-American studies" as well as a few non-American historians. Poll respondents rated the presidents in five categories (leadership qualities, accomplishments and crisis management, political skill, appointments and character and integrity) and the results were tabulated to create the overall ranking.

A 2000 survey by The Wall Street Journal consisted of an "ideologically balanced group of 132 prominent professors of history, law, and political science". This poll sought to include an equal number of liberals and conservatives in the survey as the editors argued that previous polls were dominated by either one group or the other. According to the editors, this poll included responses from more women, minorities and young professors than the 1996 Schlesinger poll. The editors noted that the results of their poll were "remarkably similar" to the 1996 Schlesinger poll, with the main difference in the 2000 poll being the lower rankings for the 1960s presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and John F. Kennedy and higher ranking of President Ronald Reagan at 8th. Franklin D. Roosevelt still ranked in the top three.

Another presidential poll was conducted by The Wall Street Journal in 2005, with James Lindgren of Northwestern University Law School for the Federalist Society. As in the 2000 survey, the editors sought to balance the opinions of liberals and conservatives, adjusting the results "to give Democratic- and Republican-leaning scholars equal weight". Franklin D. Roosevelt still ranked in the top three, but editor James Taranto noted that Democratic-leaning scholars rated George W. Bush the sixth-worst president of all time while Republican scholars rated him the sixth-best, giving him a split-decision rating of "average".

A 2006 Siena College poll of 744 professors reported the following results:

"George W. Bush has just finished five years as President. If today were the last day of his presidency, how would you rank him? The responses were: Great: 2%; Near Great: 5%; Average: 11%; Below Average: 24%; Failure: 58%"

"In your judgment, do you think he has a realistic chance of improving his rating?" Two-thirds (67%) responded no; less than a quarter (23%) responded yes; and 10% chose "no opinion or not applicable"

Thomas Kelly, professor emeritus of American studies at Siena College, said: "President Bush would seem to have small hope for high marks from the current generation of practicing historians and political scientists. In this case, current public opinion polls actually seem to cut the President more slack than the experts do". Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and director of the Siena Research Institute, stated: "In our 2002 presidential rating, with a group of experts comparable to this current poll, President Bush ranked 23rd of 42 presidents. That was shortly after 9/11. Clearly, the professors do not think things have gone well for him in the past few years. These are the experts that teach college students today and will write the history of this era tomorrow".

A 2010 Siena poll of 238 presidential scholars found that former president George W. Bush was ranked 39th out of 43, with poor ratings in handling of the economy, communication, ability to compromise, foreign policy accomplishments and intelligence. Meanwhile, the then-current president Barack Obama was ranked 15th out of 43, with high ratings for imagination, communication ability and intelligence and a low rating for background (family, education and experience).

The C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership consists of rankings from a group of presidential historians and biographers. The C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership has taken place three times: in 2000, 2009 and 2017. The most recent survey was of 91 presidential historians, surveyed by C-SPAN's Academic Advisor Team, made up of Douglas G. Brinkley, Edna Greene Medford and Richard Norton Smith. In the survey, each historian rates each president on a scale of one ("not effective" ) to 10 ("very effective" ) on presidential leadership in ten categories: Public Persuasion, Crisis Leadership, Economic Management, Moral Authority, International Relations, Administrative Skills, Relations with Congress, Vision/Setting An Agenda, Pursued Equal Justice for All and Performance Within the Context of His Times—each category is equally weighed. The results of all three C-SPAN surveys have been fairly consistent. Abraham Lincoln has taken the highest ranking in each survey and George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt have always ranked in the top five while James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson and Franklin Pierce have been ranked at the bottom of all three surveys.

In 2008, The Times daily newspaper of London asked eight of its own "top international and political commentators" to rank all 42 presidents "in order of greatness".

In 2011, through the agency of its United States Presidency Centre (USPC), the Institute for the Study of the Americas (located in the University of London's School of Advanced Study) released the first ever United Kingdom academic survey to rate presidents. This polled the opinion of British specialists in American history and politics to assess presidential performance. They also gave an interim assessment of Barack Obama, but his unfinished presidency was not included in the survey (had he been included, he would have attained eighth place overall).

In 2012, Newsweek magazine asked a panel of historians to rank the ten best presidents since 1900. The results showed that historians had ranked Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama as the best since that year.

A 2013 History News Network poll of 203 American historians, when asked to rate Obama's presidency on an A–F scale, gave him a B- grade. Obama, whom historians graded using 15 separate measures plus an overall grade, was rated most highly in the categories of communication ability, integrity and crisis management; and most poorly for his relationship with Congress, transparency and accountability.

A 2015 poll administered by the American Political Science Association (APSA) among political scientists specializing in the American presidency had Abraham Lincoln in the top spot, with George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Harry S Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, Andrew Jackson and Woodrow Wilson making the top 10. APSA conducted a repeat of this poll in 2018, with Donald Trump appearing for the first time, in last position

</snip>

There's an interactive graph further down in the article. Here's a snip of the Top 10 POTUSes, sorted by the last quoted poll, the 2018 Siena College poll:

...and the bottom 10:

August 3, 2019

42 Years Ago Today; TRS-80, the first mass-produced microcomputer, is introduced

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRS-80

TRS-80 Model I with Expansion Interface

The TRS-80 Micro Computer System (TRS-80, later renamed the Model I to distinguish it from successors) is a desktop microcomputer launched in 1977 and sold by Tandy Corporation through their RadioShack stores. The name is an abbreviation of Tandy/RadioShack, Z80 microprocessor. It is one of the earliest mass-produced and mass-marketed retail home computers.

The TRS-80 has a full-stroke QWERTY keyboard, the Zilog Z80 processor (rather than the more common Intel 8080), 4 KB DRAM standard memory (when many 8-bit computers shipped with only 1 KB RAM), small size and desk footprint, floating-point BASIC programming language, standard 64-character/line video monitor, and a starting price of US$600 (equivalent to US$2500 in 2018).

An extensive line of upgrades and add-on hardware peripherals for the TRS-80 was developed and marketed by Tandy/RadioShack. The basic system can be expanded with up to 48 KB of RAM (in 16 KB increments), and up to four floppy disk drives and/or hard disk drives. Tandy/RadioShack provided full-service support including upgrade, repair, and training services in their thousands of stores worldwide.

By 1979, the TRS-80 had the largest selection of software in the microcomputer market. Until 1982, the TRS-80 was the best-selling PC line, outselling the Apple II series by a factor of five according to one analysis.

In mid-1980, the broadly compatible TRS-80 Model III was released. The Model I was discontinued shortly thereafter, primarily due to stricter FCC regulations on radio-frequency interference to nearby electronic devices. In April 1983 the Model III was succeeded by the compatible TRS-80 Model 4.

Following the original Model I and its compatible descendants, the TRS-80 name later became a generic brand used on other technically unrelated computer lines sold by Tandy, including the TRS-80 Model II, TRS-80 Model 2000, TRS-80 Model 100, TRS-80 Color Computer and TRS-80 Pocket Computer.

History

In the mid-1970s, Tandy Corporation's RadioShack division was a successful American chain of more than 3,000 electronics stores. Among the Tandy employees who purchased a MITS Altair kit computer was buyer Don French, who began designing his own computer and showed it to vice president of manufacturing John Roach, Tandy's former electronic data processing manager. Although the design did not impress Roach, the idea of selling a microcomputer did. When the two men visited National Semiconductor in California in mid-1976, Homebrew Computer Club member Steve Leininger's expertise on the SC/MP microprocessor impressed them. National executives refused to provide Leininger's contact information when French and Roach wanted to hire him as a consultant, but they found Leininger working part-time at Byte Shop. Leininger was unhappy at National, his wife wanted a better job, and Texas did not have a state income tax. Hiring him for his technical and retail experience, Leininger and French began working together in June 1976. The company envisioned a kit, but Leininger persuaded the others that because "too many people can't solder", a preassembled computer would be better.

Tandy had 11 million customers that might buy a microcomputer, but it would be much more expensive than the US$30 median price of a RadioShack product, and a great risk for the very conservative company. Executives feared losing money as Sears did with Cartrivision, and many opposed the project; one executive told French, "Don't waste my time—we can't sell computers." As the popularity of CB radio—at one point comprising more than 20% of RadioShack's sales—declined, however, the company sought new products. In December 1976 French and Leininger received official approval for the project but were told to emphasize cost savings; for example, leaving out lowercase characters saved US$1.50 in components and reduced the retail price by US$5. The original US$199 retail price required manufacturing cost of US$80; the first design had a membrane keyboard and no video monitor. Leininger persuaded Roach and French to include a better keyboard; it, a monitor, datacassette storage, and other features required a higher retail price to provide Tandy's typical profit margin. In February 1977 they showed their prototype, running a simple tax-accounting program, to Charles Tandy, head of Tandy Corporation. The program quickly crashed as the computer could not handle the US$150,000 figure that Tandy typed in as his salary, and the two men added support for floating-point math to its Tiny BASIC to prevent a recurrence. The project was formally approved on 2 February 1977; Tandy revealed that he had already leaked the computer's existence to the press. When first inspecting the prototype, he remarked that even if it did not sell, the project could be worthy if only for the publicity it might generate.

MITS sold 1,000 Altairs in February 1975, and was selling 10,000 a year. When Tandy asked who would buy the computer, company president Lewis Kornfeld admitted that they did not know if anyone would, but suggested that small businesses and schools might. Knowing that demand was very strong for the US$795 Altair—which cost more than $1,000 with a monitor—Leininger suggested that RadioShack could sell 50,000 computers, but no one else believed him; Roach called the figure "horseshit", as the company had never sold that many of anything at that price. Roach and Kornfeld suggested 1,000 to 3,000 per year; 3,000 was the quantity the company would have to produce to buy the components in bulk. Roach persuaded Tandy to agree to build 3,500—the number of RadioShack stores—so that each store could use a computer for inventory purposes if they did not sell. RCA agreed to supply the monitor—a black-and-white television with the tuner and speakers removed—after others refused because of Tandy's low initial volume of production. Tandy used its black-and-silver colors for the TRS-80.

Having spent less than US$150,000 on development, RadioShack announced the TRS-80 (Tandy RadioShack) at a New York City press conference on August 3, 1977. It cost US$399 ($1650 today), or US$599 ($2477 today) with a 12" monitor and a RadioShack tape recorder; the most expensive product RadioShack previously sold was a US$500 stereo. The company hoped that the new computer would help RadioShack sell higher-priced products, and improve its "schlocky" image among customers. Small businesses were the primary target market, followed by educators, then consumers and hobbyists; despite its hobbyist customer base, RadioShack saw them as "not the mainstream of the business" and "never our large market".

Although the press conference did not receive much media attention because of a terrorist bombing elsewhere in the city, the computer received much more publicity at the Personal Computer Faire in Boston two days later. A front-page Associated Press article discussed the novelty of a large consumer-electronics company selling a home computer that could "do a payroll for up to 15 people in a small business, teach children mathematics, store your favorite recipes or keep track of an investment portfolio. It can also play cards". Six sacks of mail arrived at Tandy headquarters asking about the computer, over 15,000 people called to purchase a TRS-80—paralyzing the company switchboard—and 250,000 joined the waiting list with a $100 deposit.

Despite the internal skepticism, RadioShack aggressively entered the market. The company advertised "The $599 personal computer" as "the most important, useful, exciting, electronic product of our time". Kornfeld stated when announcing the TRS-80, "This device is inevitably in the future of everyone in the civilized world—in some way—now and so far as ahead as one can think", and Tandy's 1977 annual report called the computer "probably the most important product we've ever built in a company factory". Unlike competitor Commodore—which had announced the PET several months earlier but had not yet shipped any—Tandy had its own factories (capable of producing 18,000 computers a month) and distribution network, and even small towns had RadioShack stores. The company announced plans to be selling by Christmas a range of peripherals and software for the TRS-80, began shipping computers by September, opened its first computer-only store in October, and delivered 5,000 computers to customers by December. Still forecasting 3,000 sales a year, RadioShack sold over 10,000 TRS-80s Model Is in its first one and a half months of sales, 55,000 in its first year, and over 200,000 during the product's lifetime; one entered the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. By mid-1978 the waits of two months or more for delivery were over, and the company could state in advertisements that TRS-80 was "on demonstration and available from stock now at every RadioShack store in this community!".

The TRS-80 Model I pictured alongside the Apple II and the Commodore PET 2001-8. These three computers constitute what Byte Magazine called the "1977 Trinity" of home computing.

The first units, ordered unseen, were delivered in November 1977, and rolled out to the stores the third week of December. The line won popularity with hobbyists, home users, and small-businesses. Tandy Corporation's leading position in what Byte magazine called the "1977 Trinity" (Apple, Commodore and Tandy) had much to do with Tandy's retailing the computer through more than 3,000 of its RadioShack storefronts in the USA.[26] Tandy claimed it had "7000 [RadioShack] stores in 40 countries". The pre-release price for the basic system (CPU/keyboard and video monitor) was US$500 and a US$50 deposit was required, with a money-back guarantee at time of delivery.

By 1978, Tandy/RadioShack promoted itself as "The Biggest Name in Little Computers". By 1980, InfoWorld described RadioShack as "the dominant supplier of small computers". Kilobaud Microcomputing estimated that it was selling three times as many computers as Apple Computer, with both companies ahead of Commodore. By 1979 1,600 employees built computers in six factories.[10] By 1981 hundreds of small companies produced TRS-80 software and accessories, and Adam Osborne described Tandy as "the number-one microcomputer manufacturer" despite having "so few roots in microcomputing". Roach became Tandy's CEO that year, Leininger became director of strategic planning, and French founded a software company. Selling computers did not change the company's "schlocky" image; the RadioShack name embarrassed business customers, and Tandy executives disliked the "Trash-80" nickname for its products. By 1984 computers accounted for 35% of sales, however, and the company had 500 Tandy RadioShack Computer Centers.

Following the Model III launch in mid-1980 Tandy stated that the Model I was still sold, but it was discontinued by the end of the year. Tandy cited one of the main reasons as being the prohibitive cost of redesigning it to meet stricter FCC regulations covering the significant levels of radio-frequency interference emitted by the original design. The Model I radiated so much interference that, while playing games, an AM radio placed next to the computer could be used to provide sounds. Radio Shack offered upgrades (double density floppy controller, LDOS, memory, reliable keyboard with numeric keypad, lowercase, Level II, RS-232C) as late as 1985.

</snip>

TRS-80 Model I with Expansion Interface

The TRS-80 Micro Computer System (TRS-80, later renamed the Model I to distinguish it from successors) is a desktop microcomputer launched in 1977 and sold by Tandy Corporation through their RadioShack stores. The name is an abbreviation of Tandy/RadioShack, Z80 microprocessor. It is one of the earliest mass-produced and mass-marketed retail home computers.

The TRS-80 has a full-stroke QWERTY keyboard, the Zilog Z80 processor (rather than the more common Intel 8080), 4 KB DRAM standard memory (when many 8-bit computers shipped with only 1 KB RAM), small size and desk footprint, floating-point BASIC programming language, standard 64-character/line video monitor, and a starting price of US$600 (equivalent to US$2500 in 2018).