marble falls

marble falls's JournalBlack history month day 5: Carter G. Woodson - father of Black History (Negro History Week in 1926)

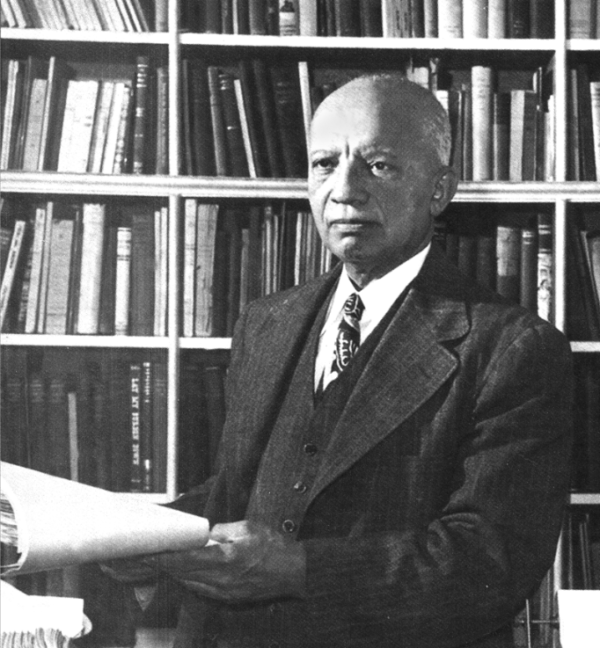

Carter G. Woodson

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950)[1] was an American historian, author, journalist and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been cited as the "father of black history".[2] In February 1926 he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week", the precursor of Black History Month.[3]

Early life and education

Carter G. Woodson was born in New Canton, Buckingham County, Virginia[4] on December 19, 1875, the son of former slaves, Anne Eliza (Riddle) and James Henry Woodson.[5] His parents were both illiterate and his father, who had helped the Union soldiers during the Civil War, supported the family as a carpenter and farmer. Woodson was often unable to regularly attend primary school so as to help out on the farm. Nonetheless, through self-instruction, he was able to master most school subjects.[6]

At the age of seventeen, Woodson followed his brother to Huntington, where he hoped to attend the brand new secondary school for blacks, Douglass High School. However, Woodson, forced to work as a coal miner, was able to devote only minimal time each year to his schooling. In 1895, the twenty-year-old Woodson finally entered Douglass High School full-time, and received his diploma in 1897. [7][8] From 1897 t 1900, Woodson taught at Winona in Fayette County. In 1900 he was selected as the principal of Douglass High School. He earned his Bachelor of Literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1903 by taking classes part-time between 1901 and 1903. From 1903 to 1907, Woodson was a school supervisor in the Philippines.

Woodson later attended the University of Chicago, where he was awarded an A.B. and A.M. in 1908. He was a member of the first black professional fraternity Sigma Pi Phi[9] and a member of Omega Psi Phi. He completed his PhD in history at Harvard University in 1912, where he was the second African American (after W. E. B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate.[10] His doctoral dissertation, The Disruption of Virginia, was based on research he did at the Library of Congress while teaching high school in Washington, D.C. After earning the doctoral degree, he continued teaching in public schools, later joining the faculty at Howard University as a professor, and served there as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Career

Convinced that the role of his own people in American history and in the history of other cultures was being ignored or misrepresented among scholars, Woodson realized the need for research into the neglected past of African Americans. Along with William D. Hartgrove, George Cleveland Hall, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History on September 9, 1915, in Chicago.[11] That was the year Woodson published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. His other books followed: A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The History of the Negro Church (1927). His work The Negro in Our History has been reprinted in numerous editions and was revised by Charles H. Wesley after Woodson's death in 1950.

In January 1916, Woodson began publication of the scholarly Journal of Negro History. It has never missed an issue, despite the Great Depression, loss of support from foundations, and two World Wars. In 2002, it was renamed the Journal of African American History and continues to be published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).

Woodson stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA during visits to Chicago. His experiences at the Y and in the surrounding Bronzeville neighborhood inspired him to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), which ran conferences, published The Journal of Negro History, and "particularly targeted those responsible for the education of black children".[12] Another inspiration was John Wesley Cromwell's 1914 book, The Negro in American History: Men and Women Eminent in the Evolution of the American of African Descent.[13]

Woodson believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among blacks and whites could reduce racism and he promoted the organized study of African-American history partly for that purpose. He would later promote the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926, forerunner of Black History Month.[14]The Bronzeville neighborhood declined during the late 1960s and 1970s like many other inner-city neighborhoods across the country, and the Wabash Avenue YMCA was forced to close during the 1970s, until being restored in 1992 by The Renaissance Collaborative.[15]

He served as Academic Dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute, now West Virginia State University, from 1920 to 1922.[16]

He studied many aspects of African-American history. For instance, in 1924, he published the first survey of free black slaveowners in the United States in 1830.[17]

NAACP

Woodson became affiliated with the Washington, D.C. branch of the NAACP, and its chairman Archibald Grimké. On January 28, 1915, Woodson wrote a letter to Grimké expressing his dissatisfaction with activities and making two proposals:

<snip>

Du Bois added the proposal to divert "patronage from business establishments which do not treat races alike," that is, boycott businesses. Woodson wrote that he would cooperate as one of the twenty-five effective canvassers, adding that he would pay the office rent for one month. Grimké did not welcome Woodson's ideas.[citation needed]

Responding to Grimké's comments about his proposals, on March 18, 1915, Woodson wrote:

I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. In fact, I should welcome such a law suit. It would do the cause much good. Let us banish fear. We have been in this mental state for three centuries. I am a radical. I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me.[18]

His difference of opinion with Grimké, who wanted a more conservative course, contributed to Woodson's ending his affiliation with the NAACP.[citation needed]

Black History Month

Woodson devoted the rest of his life to historical research. He worked to preserve the history of African Americans and accumulated a collection of thousands of artifacts and publications. He noted that African-American contributions "were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."[19] Race prejudice, he concluded, "is merely the logical result of tradition, the inevitable outcome of thorough instruction to the effect that the Negro has never contributed anything to the progress of mankind."[19]

In 1926, Woodson pioneered the celebration of "Negro History Week",[20] designated for the second week in February, to coincide with marking the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.[21] However, it was the Black United Students and Black educators at Kent State University that founded Black History Month, on February 1, 1970.[22]

Colleagues

Woodson believed in self-reliance and racial respect, values he shared with Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist who worked in New York. Woodson became a regular columnist for Garvey's weekly Negro World.

Woodson's political activism placed him at the center of a circle of many black intellectuals and activists from the 1920s to the 1940s. He corresponded with W. E. B. Du Bois, John E. Bruce, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Hubert H. Harrison, and T. Thomas Fortune, among others. Even with the extended duties of the Association, Woodson was able to write academic works such as The History of the Negro Church (1922), The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), and others which continue to have wide readership.

Woodson did not shy away from controversial subjects, and used the pages of Black World to contribute to debates. One issue related to West Indian/African-American relations. He summarized that "the West Indian Negro is free", and observed that West Indian societies had been more successful at properly dedicating the necessary amounts of time and resources needed to educate and genuinely emancipate people. Woodson approved of efforts by West Indians to include materials related to Black history and culture into their school curricula.[citation needed]

Woodson was ostracized by some of his contemporaries because of his insistence on defining a category of history related to ethnic culture and race. At the time, these educators felt that it was wrong to teach or understand African-American history as separate from more general American history. According to these educators, "Negroes" were simply Americans, darker skinned, but with no history apart from that of any other. Thus Woodson's efforts to get Black culture and history into the curricula of institutions, even historically Black colleges, were often unsuccessful.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

Woodson died suddenly from a heart attack in the office within his home in the Shaw, Washington, D.C. neighborhood on April 3, 1950, at the age of 74. He is buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland

The time that schools have set aside each year to focus on African-American history is Woodson's most visible legacy. His determination to further the recognition of the Negro in American and world history, however, inspired countless other scholars. Woodson remained focused on his work throughout his life. Many see him as a man of vision and understanding. Although Woodson was among the ranks of the educated few, he did not feel particularly sentimental about elite educational institutions.[citation needed] The Association and journal that he started are still operating, and both have earned intellectual respect.

Woodson's other far-reaching activities included the founding in 1920 of the Associated Publishers, the oldest African-American publishing company in the United States. This enabled publication of books concerning blacks that might not have been supported in the rest of the market. He founded Negro History Week in 1926 (now known as Black History Month). He created the Negro History Bulletin, developed for teachers in elementary and high school grades, and published continuously since 1937. Woodson also influenced the Association's direction and subsidizing of research in African-American history. He wrote numerous articles, monographs and books on Blacks. The Negro in Our History reached its 11th edition in 1966, when it had sold more than 90,000 copies.

Dorothy Porter Wesley recalled: "Woodson would wrap up his publications, take them to the post office and have dinner at the YMCA. He would teasingly decline her dinner invitations saying, 'No, you are trying to marry me off. I am married to my work'".[23] Woodson's most cherished ambition, a six-volume Encyclopedia Africana, was incomplete at the time of his death.

Honors and tributes

<snip>

Black History, day 4: Jerry Lawson (engineer)

Jerry Lawson (engineer)

?quality=99&strip=all&w=660

?quality=99&strip=all&w=660

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerry_Lawson_(engineer)

Gerald Anderson "Jerry" Lawson (December 1, 1940 – April 9, 2011)[1][2] was an American electronic engineer, and one of the few African-American engineers in the industry at that time. He is known for his work in designing the Fairchild Channel F video game console as well as inventing the video game cartridge.[3]

Early life

Lawson was born in Brooklyn, New York City on December 1, 1940.[4] His father Blanton was a longshoreman with an interest in science, while his mother Mannings worked for the city, and also served on the PTA for the local school and made sure that he received a good education.[5] Both encouraged his interests in scientific hobbies, including ham radio and chemistry. Lawson said that his first-grade teacher helped him encourage his path to be someone influential similar to George Washington Carver.[4] While in high school, he earned money by repairing television sets. He attended both Queens College and City College of New York, but did not complete a degree at either.[4]

Career

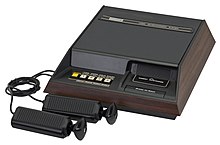

The Fairchild Channel F, with the cartridge slot on the right of the unit

In 1970, he joined Fairchild Semiconductor in San Francisco as an applications engineering consultant within their sales division. While there, he created the early arcade game Demolition Derby out of his garage.[4][5] In the mid-1970s, Lawson was made Chief Hardware Engineer[6] and director of engineering and marketing for Fairchild's video game division.[4] There, he led the development of the Fairchild Channel F console, released in 1976 and specifically designed to use swappable game cartridges. At the time, most game systems had the game programming stored on ROM storage soldered onto the game hardware, which could not be removed. Lawson and his team figured out how to move the ROM to a cartridge that could be inserted and removed from a console unit repeatedly, and without electrically shocking the user. This would allow users to buy into a library of games, and provided a new revenue stream for the console manufacturers through sales of these games.[7] Lawson's invention of the interchangeable cartridge was so novel that every cartridge he produced had to be approved by the Federal Communications Commission.[8] The Channel F was not a commercially successful product, but the cartridge approach was picked up by other console manufacturers, popularized with the Atari 2600 released in 1977.[9][10]

While he was with Fairchild, Lawson and Ron Jones were the sole black members of the Homebrew Computer Club, a group of early computer hobbyists which would produce a number of industry legends, including Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.[9] Lawson had noted he had interviewed Wozniak for a position at Fairchild, but did not hire him.[4]

In 1980, Lawson left Fairchild and founded Videosoft, a video game development company which made software for the Atari 2600 in the early 1980s, as the 2600 had displaced the Channel F as the top system in the market.[3][11] Videosoft closed about five years later, and Lawson started to take on consulting work. At one point, he had been working with Stevie Wonder to produce a "Wonder Clock" that would wake a child with the sound of a parent's voice, though it never made it to production.[7] Lawson later worked with the Stanford mentor program and was preparing to write a book on his career.[9]

In March 2011, Lawson was honored as an industry pioneer for his work on the game cartridge concept by the International Game Developers Association (IGDA).[7]

Death

Around 2003, Lawson started having complications from diabetes, losing the use of one leg and sight from one eye.[5] On April 9, 2011, about one month after being honored by the IGDA, he died of complications from diabetes.[4][7] At the time of his death, he resided in Santa Clara, California, and was survived by his wife, two children, and his brother.[4]

Black History: day 3 Before there was Rosa Parks, there was Claudette Colvin.

Before there was Rosa Parks, there was Claudette Colvin.

http://www.pbs.org/black-culture/explore/10-black-history-little-known-facts/

Most people think of Rosa Parks as the first person to refuse to give up their seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. There were actually several women who came before her; one of whom was Claudette Colvin.

It was March 2, 1955, when the fifteen-year-old schoolgirl refused to move to the back of the bus, nine months before Rosa Parks’ stand that launched the Montgomery bus boycott. Claudette had been studying Black leaders like Harriet Tubman in her segregated school, those conversations had led to discussions around the current day Jim Crow laws they were all experiencing. When the bus driver ordered Claudette to get up, she refused, “It felt like Sojourner Truth was on one side pushing me down, and Harriet Tubman was on the other side of me pushing me down. I couldn't get up."

Claudette Colvin’s stand didn’t stop there. Arrested and thrown in jail, she was one of four women who challenged the segregation law in court. If Browder v. Gayle became the court case that successfully overturned bus segregation laws in both Montgomery and Alabama, why has Claudette’s story been largely forgotten? At the time, the NAACP and other Black organizations felt Rosa Parks made a better icon for the movement than a teenager. As an adult with the right look, Rosa Parks was also the secretary of the NAACP, and was both well-known and respected – people would associate her with the middle class and that would attract support for the cause. But the struggle to end segregation was often fought by young people, more than half of which were women.

Image: Claudette Colvin by Phillip Hoose

Black history Pg 2: Stoop Summit - How a Harlem brownstone was immortalized

Stoop Summit

How a Harlem brownstone was immortalized when the living legends of jazz assembled there for an iconic photograph

BY SARAH GOODYEAR

FRIDAY, AUGUST 12, 2016

http://interactive.nydailynews.com/2016/08/story-behind-great-day-in-harlem-photo/

A tip of the hat to Malaise and Brother Buzz!!!

&f=1

This photo at the link is interactive and really interesting to use

A recurring series on iconic scenes from the city’s storied culture.

The year was 1999, and Noella Cotto was just looking for a place in Harlem to call her own. When she finally found the perfect place — a brownstone, in decent shape, at 17 E. 126th Street — she had no idea that the building had played a historic supporting role in American pop culture when, in 1958, 57 of the coolest cats in jazz assembled there to have their picture taken for a special issue of Esquire magazine. Cotto, who worked as a postal cop at the time, was unaware that the famous photo, titled “Harlem 1958,” was ubiquitous around the neighborhood, or that a generation of folks who’d grown up in the so-called Cultural Capital of Black America had seen the image so often, hanging in barber shops and bodegas, that they’d long since forgotten about it themselves. Nor did she realize that the photo had gotten another close-up only five years earlier in an Oscar-nominated documentary, “A Great Day in Harlem.”

The whole audacious idea was conceived by a man who none of the musicians knew, 33-year-old Art Kane, who had made a name for himself as a magazine art director but whose passion was photography. This was his first professional shooting assignment and, with it, he ended up making history almost by accident.

“He became aware that Esquire was planning a big issue on jazz,” says Jonathan Kane, Art’s son, a musician and photographer who also manages his late father’s photographic legacy (Art Kane died in 1995). “He cooked up the idea of doing a big portrait (with) all these musicians. Art pitched his crazy idea, and they said, Do it.” There was no question about where he would shoot. “Harlem was where the jazz scene came into being and coalesced,” Kane says. “It had to be in Harlem. And he wanted a place that reflected everyday life rather than a club. This could be a street where anybody could live.”

After scouting for a typical building on a typical block, Kane chose 126th St. between Fifth and Madison Aves. He wanted one that was convenient to the subway and what was then the New York Central Railroad (now Metro North), which had a station at 125th and Park. He put out the call for musicians through agents, record labels, union halls, clubs — pretty much any channel he could think of.

One of the musicians answering the call was Sonny Rollins, the brilliant tenor saxophonist who was 27 years old when the picture was shot and already among the period’s most acclaimed jazz artists. Rollins, who says he started playing music when he was 7 or 8 years old, had grown up in central Harlem, surrounded by the ferment of jazz. “All of the black musicians lived in Harlem, it was the only place you could live,” he says. “Harlem was the place. All my idols, like Fats Waller, all these people performed around where I went to school, at P.S. 89, at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue. So it was quite a community.”

“There were musicians from several eras of jazz. That picture depicted what a robust scene it was for jazz musicians in New York.”

— Sonny Rollins

When he heard about the photo shoot, he knew he had to be there. “I didn’t hesitate,” says Rollins, who is now 85 and, along with Benny Golson, one of only two surviving musicians in the photo. “Something like that had never been done, and the guys were just eager to do it. I certainly was eager to do it. They were all my compadres. It was great fun.”

They had fun even though the start time, in jazz terms, was brutal. Because he wanted to utilize the best light on the north side of the street, avoiding any shadows, Kane asked people to arrive by 10 a.m. — a tall order for artists who typically worked until 4 in the morning. In the 1994 documentary about the photograph, Steve Frankfurt, who was assisting Kane that day, put that early call time in perspective: “Somebody said they didn’t realize there were two 10 o’clocks in the same day.”

The nighthawks showed up anyway, dressed to the nines and ready for action. They came by subway and commuter train. They came by taxi and on foot. Among the greats who made the gig that morning were Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Gene Krupa, Mary Lou Williams, Roy Eldridge, Milt Hinton and Lester Young. It was a crazy scene, made even more beautiful by the row of neighborhood kids who sat in a row along the curb alongside a jovial Count Basie. “There were musicians from several eras of jazz,” Rollins says. “I think that picture depicted what a robust scene it was for jazz musicians in New York.”

history

Jonathan Kane

HISTORY IN THE MAKING The January 1959 issue of Esquire in which Art Kane’s photo originally appeared.

“A Great Day in Harlem” dives into the story behind the picture in detail, incorporating the priceless, joy-infused Super-8 footage that Mona Hinton, Milt’s wife, shot during the session. It shows the musicians milling about, greeting each other, telling stories, laughing — doing just about everything but paying attention to the photographer across the street, who implored them to come into formation through a megaphone improvised from a rolled-up newspaper.

<BIG snip>

Jonathan Kane says. “(The photograph) has become part of our cultural fabric.”

TAKE THE 2/3 TRAIN The brownstone at 17 E. 126th Street today, with the tripod photographer Art Kane used when shooting “Harlem 1958.”

This article is so worth the reading!

I'm going to post one of these every day. This one I chose because it was so near where I ...

grew up. I want to learn all the stuff I should have learned about in school. My history I was was taught over and over. Our history I didn't learn very much about at all. I am the poorer for it. I learned a liberal sort of racism: blacks couldn't contribute because they were held back. They were held back but they certainly did contribute in bigger ways than anecdotes.

Black history month: John Mercer Langston was the first black man to become a lawyer

First Lawyer:John Mercer Langston was the first black man to become a lawyer when he passed the bar in Ohio in 1854. When he was elected to the post of Town Clerk for Brownhelm, Ohio, in 1855 Langston became one of the first African Americans ever elected to public office in America. John Mercer Langston was also the great-uncle of Langston Hughes, famed poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-history-facts

Do you think that state interests are all the same? Then why are there still agriculteral ...

checkpoints between some states? Why aren't all state's state laws all the same? Why is there an Interstate Commerce Commission to deal with trade issues between states? Why are there trade issues between states? Have you ever heard of the fights between Arizona, California, Colorado, Mexico and various Tribal Nations over the Colorado River?

We aren't all the same. We all have different issues and interests.

Do you really want Texas's interest in tar sand oil from Canada and the Keystone Pipeline permutations to "trump" Nebraska, Oklahoma, Kansas, N Dakota and S Dakota's interest in not having "petroleum" or what ever chemical nightmare that keeps it "liquid" spills over fields over one the largest freshwater aquifers in the US?

It works the other way, too. Contrary to what some may hear, Trumpolini's wall is not that popular here, especially the closer to the border you go. Why are a bunch of conservative yahoos from up north trying to foist their wall on us? AND in that we're the second most populated state we're going to pay more than forty-eight other states for a project that will impact us more than forty-nine other states. One we don't want.

My point is its part of the checks and balances that allow us not to become victims of what T Jefferson called "the tyranny of the majority." For example: minorities get to vote regardless of how the majorities feel about it. Because we all have different interests and issues.

In these days of situational ethics we need to protect ourselves.

Julian Assange must have gotten the news about Roger Stone ...

The Ecuadorian Embassy has reported Assange made his bed, took a shower and cleaned the cat's litter box at 6:30 AM EST.

Woody Guthrie sings about racist "Old Man Trump".

4 Arrested Over Alleged Plot To Bomb Muslim Enclave In New York

Source: HuffPo

4 Arrested Over Alleged Plot To Bomb Muslim Enclave In New York

“If they had carried out this plot, which every indication is that they were going to, people would have died,” the Greece, New York, police chief said.

?ops=scalefit_720_noupscale

?ops=scalefit_720_noupscale

By Nick Visser

<snip>

Investigators said they first heard of the plot after a student at Greece Odyssey Academy in Greece, New York, made an offhand remark during a lunch break, which prompted another student to report the comment to school officials. Greece Police Chief Patrick Phelan said authorities quickly responded to the report, conducting interviews and making arrests that same day.

The suspects allegedly planned to target the Muslim enclave of Islamberg, a small area in the Catskill Mountains about 150 miles from New York City, according to Reuters. Authorities later said they seized 23 weapons and three improvised explosive devices while carrying out search warrants. All of the firearms were legally owned by relatives of those arrested.

<snip>

The suspects were identified as Brian Colaneri, 20, Andrew Crysel, 18, and Vincent Vetromile, 19. They have each been charged with three felony counts of first-degree possession of a dangerous weapon and one felony count of fourth-degree conspiracy. An unidentified 16-year-old student was also charged with the same crimes but will be tried as a minor.

Phelan said school officials first became suspicious after a student reported the 16-year-old showing a photo on his phone to some friends in the school cafeteria. The student allegedly made a comment to the effect of “he looks like the next school shooter, doesn’t he?” which prompted the complaint.

<snip>

Read more: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/bomb-islamberg-new-york-muslim-community_us_5c47ddc5e4b083c46d6399ea

More about Islamburg: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamberg%2C_New_York

More privileged white kids in a private school.

Profile Information

Name: had to removeGender: Do not display

Hometown: marble falls, tx

Member since: Thu Feb 23, 2012, 04:49 AM

Number of posts: 57,063