Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

General Discussion

Showing Original Post only (View all)Climate scientists: concept of net zero is a dangerous trap [View all]

The US has joined the EU in committing to net-zero emissions by 2050—and the latter to 55 per cent net lower emissions by 2030. Scientists fear the ‘net’ could displace urgency.

https://www.socialeurope.eu/climate-scientists-concept-of-net-zero-is-a-dangerous-trap

Sometimes realisation comes in a blinding flash. Blurred outlines snap into shape and suddenly it all makes sense. Underneath such revelations is typically a much slower-dawning process. Doubts at the back of the mind grow. The sense of confusion that things cannot be made to fit together increases until something clicks. Or perhaps snaps. Collectively we three authors of this article must have spent more than 80 years thinking about climate change. Why has it taken us so long to speak out about the obvious dangers of the concept of net zero? In our defence, the premise of net zero is deceptively simple—and we admit that it deceived us. The threats of climate change are the direct result of there being too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. So it follows that we must stop emitting more and even remove some of it. This idea is central to the world’s current plan to avoid catastrophe. In fact, there are many suggestions as to how to actually do this, from mass tree planting, to high tech direct air capture devices that suck out carbon dioxide from the air.

The current consensus is that if we deploy these and other so-called ‘carbon-dioxide removal’ techniques at the same time as reducing our burning of fossil fuels, we can more rapidly halt global warming. Hopefully around the middle of this century we will achieve ‘net zero’. This is the point at which any residual emissions of greenhouse gases are balanced by technologies removing them from the atmosphere. This is a great idea, in principle. Unfortunately, in practice it helps perpetuate a belief in technological salvation and diminishes the sense of urgency surrounding the need to curb emissions now. We have arrived at the painful realisation that the idea of net zero has licensed a recklessly cavalier ‘burn now, pay later’ approach which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar. It has also hastened the destruction of the natural world by increasing deforestation today, and greatly increases the risk of further devastation in the future. To understand how this has happened, how humanity has gambled its civilisation on no more than promises of future solutions, we must return to the late 1980s, when climate change broke out onto the international stage.

Steps towards net zero

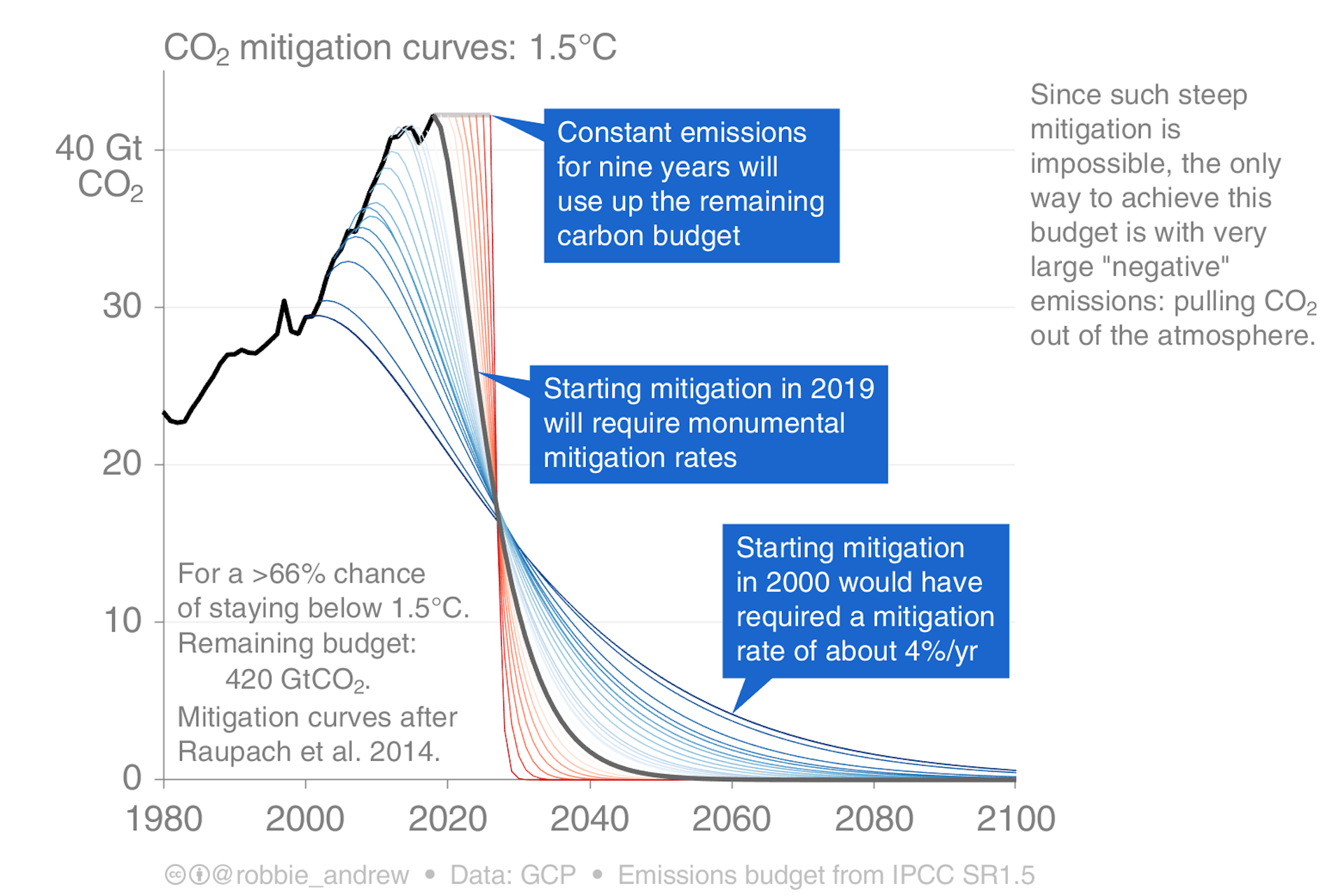

On June 22nd 1988, James Hansen was the administrator of Nasa’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, a prestigious appointment but someone largely unknown outside of academia. By the afternoon of the 23rd he was well on the way to becoming the world’s most famous climate scientist. This was as a direct result of his testimony to the US Congress, when he forensically presented the evidence that the earth’s climate was warming and that humans were the primary cause: ‘The greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.’ If we had acted on Hanson’s testimony at the time, we would have been able to decarbonise our societies at a rate of around 2 per cent a year in order to give us about a two-in-three chance of limiting warming to no more than 1.5°C. It would have been a huge challenge, but the main task at that time would have been to simply stop the accelerating use of fossil fuels while fairly sharing out future emissions.

Four years later, there were glimmers of hope that this would be possible. During the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, all nations agreed to stabilise concentrations of greenhouse gases to ensure that they did not produce dangerous interference with the climate. The 1997 Kyoto summit attempted to start to put that goal into practice. But as the years passed, the initial task of keeping us safe became increasingly hard, given the continual increase in fossil fuel use. It was around that time that the first computer models linking greenhouse-gas emissions to impacts on different sectors of the economy were developed. These hybrid climate-economic models are known as integrated assessment models. They allowed modellers to link economic activity to the climate by, for example, exploring how changes in investments and technology could lead to changes in greenhouse-gas emissions. They seemed like a miracle: you could try out policies on a computer screen before implementing them, saving humanity costly experimentation. They rapidly emerged to become key guidance for climate policy. A primacy they maintain to this day.

snip

much more at the top link

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

4 replies, 867 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (8)

ReplyReply to this post

4 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

The world as a whole will not do enough until it is too late and 2050 is too late.

marie999

May 2021

#1