Economy

Related: About this forumBook or website suggestion needed

Over the last year I have heard both good and bad about John Maynard Keynes. Oddly enough this is sometime by the same people, they accept part of his theories and disregard other. I would like to know more about his history and theory, mostly theory.

Does anyone know of a book or website which can explain Keyensian theory for someone who does not have an economics degree. If there were a Keyensian Theory for Dummies, that would do nicely.

Scootaloo

(25,699 posts)Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keynesian_economics

Warpy

(111,255 posts)There are two things that prove what a towering figure Keynes has been: first, his model worked in practice; and second, every other economist out there has been desperate to prove him wrong about something, even Krugman.

WCGreen

(45,558 posts)The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism [Paperback] is the full name and the author is Joyce Appleby.

It's a pretty quick read and you get an idea of how the western markets developed. I think it essential to learn the history in order to understand why things became as they are. Then read Keynes...

SoutherDem

(2,307 posts)Komputernut

(16 posts)If your serious about learning economics and about many of the forces that shape it in the real world and your looking for an excellent easy to understand series that covers the entire spectrum from a person that gives his perspectives in a non-partisan way I recommend Timothy Taylor. You mention Keynes and he is covered at some length in context.

He has a long audio series he did with the teaching company which when I purchased over 10 years ago it was several hundred dollars. Today the price is around $50 (for audio download). I have the videos, but to be honest the audio is just as good as he doesn't do any whiteboard work that I recall..... If your at all serious about understanding the economy, this audio book series is excellent.

With all the free content on the internet $50 is a lot, but if you have the money to spare, I believe it's money well spent.

http://www.thegreatcourses.com/tgc/courses/course_detail.aspx?cid=550

If your internet savvy you might even be able to find this other places....

DanTex

(20,709 posts)The "General Theory" is long and not the easiest read in the world. Here are some other possible suggestions:

Maybe buy a textbook on macroeconomics (or find some course notes online). The IS-LM model is roughly accurate interpretation of the basic Keynesian ideas.

Also, read Paul Krugman's blog. He does a pretty good job of explaining Keynesian economics and how it relates to the current situation in a not-too-technical way, and then he also has his "wonkish" posts where he goes into more detail if you're interested.

Of course, don't let this dissuade you from actually reading Keynes if you want to, just if you find it difficult, there are other routes.

RommelDAK

(21 posts)I completely agree that the General Theory is very hard to read, but I would caution people to steer clear of IS-LM. Anyone who has actually read the General Theory can find little in common between it and John Hick's IS-LM (including my intermediate macro students, when I have them go through that exercise!).

I apologize for recommending something I wrote, but my goal was to lay out a Keynes' (rather than Keynesian, which isn't the same thing!) view of how the economy works, and it's written for the layperson:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/johntharvey/2011/04/18/why-do-recessions-happen-a-practical-guide-to-the-business-cycle/

Or there is this, which is a bit longer:

http://www.econ.tcu.edu/harvey/blog/summary.pdf

DanTex

(20,709 posts)While I agree that IS-LM may not be true to Keynes's ideas from "General Theory", I still think it's probably a good idea for someone interested in Keynesian economics to at least understand IS-LM. If only because IS-LM is often what people (economists/pundits) have in mind when they say the words "Keynsian economics" (as you suggest Keynes's view and the "Keynesian view" are not always the same). And, while it does leave out some important aspects of Keynes's actual ideas, it does capture some important ones.

In fact, probably the most important concept that distinguishes Keynesian economics is that, in the short run, the labor market can fail to clear, and so the economy can operate at less than full employment for "non-structural" reasons, justifying the use of monetary and/or fiscal policy to restore full employment. And this is present in IS-LM.

For example here are some lecture notes from a course by Nouriel Roubini:

http://people.stern.nyu.edu/nroubini/NOTES/CHAP9.HTM#topic0

An important issue related to this non-neutrality of money is the behavior of central banks and monetary policy. During recessions, the Fed expands the level and/or growth rate of the money supply to reduce interest rates and stimulate economic activity. What is the logic of such a policy ? If the world was working according to the Classical Theory in the short-run, such Fed policy would have no real effects and will only increase inflation. Figure 1 shows the effects of an increase in the rate of growth of money in the Classical model. An increase in the rate of growth of money leads to an immediate proportional increase in the inflation rate, in the nominal interest rate with no effects on the real interest rate and the level of output. Money is neutral both in the short-run and the long-run.

However, empirical evidence shows that an increase in the rate of growth of the money supply has very different effects in the short-run from those predicted by the Classical Theory. The response in reality is more similar to that shown in Figure 2: higher money growth reduces the nominal and real interest rate in the short run and leads to an increase in the rate of inflation only slowly over time. The reduction in the real interest rate, in turn, leads to a short-run increase in investment, consumption and the level of output. To understand why monetary policy has effects similar to those shown in Figure 2, we have to look at the Keynesian Theory where prices adjust slowly (with inertia) in the short-run.

RommelDAK

(21 posts)Howdy, fellow Texan (or so I am assuming!)!

While I agree that IS-LM is far superior to the other crap out there (Monetarism, Real Business Cycles, New Classical, etc.), it is still a long way from Keynes. I think probably the biggest difference is that the IS-LM/Keynesian approach still assumes that the economy basically takes care of itself, but that some sort of imperfection keeps it from operating properly (inflexible wages are usually cited). All of the so-called progressive economists (Krugman, Romer, etc.) believe this. But, Keynes said no such thing. He argued that in a pure, free market economy with no rigidities, there is still no guarantee of full employment. Far from it, it’s likely to break down and be in slump more often than expansion.

This is what Keynes actually said. First off, let’s say we have a situation in which the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity of labor demanded (i.e., involuntary unemployment). The market doesn’t clear because wages are downwardly inflexible, right? Otherwise the unemployment would go away. That’s not what Keynes said. First, such a position is already in equilibrium. Workers are happy and firms are happy–only the involuntarily unemployed are dissatisfied. However, they have no mechanism available to change their situation. In an intro micro class, we might say, “They will offer to work for less.” But, the real world doesn’t work that way. Offer to whom? The firms aren’t hiring and already have a work force that allows them to maximize profits given the current wage rate (because the traditional demand for labor curve is simply the marginal product of labor curve). Indeed, there are folks right this second or during the Great Depression who are/were perfectly willing to work for less than what current workers are earning, but they still can’t find employment. The bottom line is that in Keynes’ labor market, every point on the labor demand curve above the intersection with labor supply is an equilibrium point.. THIS DOES NOT REQUIRE THAT WE ASSUME SOME SORT OF INEFFICIENCY OR RIGIDITY IN MARKETS. That’s simply the way labor markets work. Involuntary unemployment does not set into motion forces that automatically correct it.

That’s around chapter two of the General Theory. Then he shifts gears, and initially in a way that is not inconsistent with IS-LM, albeit for a different reason (i.e., not rigidities). He says that the real key is insufficient demand, not wages. The classicals had the focus on the wrong variable. However–and here is the second big break with the Keynesians–Keynes doesn’t blame exogenous policy shocks for insufficient demand, but the internal dynamic of the capitalist system. In very, very brief terms, physical investment spending (i.e., not financial) drives the macroeconomy. However, it is quickly saturated. When it declines, workers are laid off, spending falls, sentiment becomes pessimistic, and recession sets in. After the passage of some time, firms gain the confidence to invest again (as old equipment needs replacement, for example) and investment rises again, driving the economy upwards. THIS is the key to Keynes’ argument. It is an endogenous business cycle that appears nowhere in John Hicks’ IS-LM apparatus (in fact, Hicks himself later rejected it). In IS-LM, everything happens because you shifted one of the curves. In Keynes, it is an systemic cycle of expansion and recession, even in a pure, free market economy with absolutely, positively no rigidities..

In short, what Roubini says in paragraph one is dead wrong. And what he implicitly argues in the next two paragraphss, i.e., that monetary policy plays an important role in Keynes’ view, is also false.

But don’t take my word for it. To get a quick sense of all this from the General Theory, read his chapter 22: Notes on the Trade Cycle:

http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/keynes/general-theory/ch22.htm

It is one of my all-time favorites and I’ve written a couple of articles on it. Check it out and see how little of what is there actually shows up in IS-LM. To be honest, I think the world would be a better place had the latter never been invented. It almost immediately (1937) aborted Keynes’ revolution (1936). IS-LM isn’t much more than classical economics with some Keynesian terminology.

DanTex

(20,709 posts)First off, thanks for the stimulating discussion. Now I have to go read "General Theory" again. And when I say "again", really what I basically mean is "for the first time"...

I don't really see what you are saying as all that different from "downwards nominal rigidity". In principle, in the situation you describe above, firms could either cut the wages of their current workers, or fire their current workers and hire new ones at a lower wage. In theory, assuming the lower wage workers were equally skilled and productive, this would make the firms more profitable -- they produce the same amount of stuff at lest cost. But in reality they don't do that -- wages are sticky.

In other words, describing this situation as "equilibrium" is sort of equivalent to saying "wages are sticky". Without the stickiness of wages, this would not be an equilibrium, because firms could cut wages and achieve a strictly better outcome.

As for the business cycle, I agree with you, IS-LM doesn't give any endogenous explanation for why there are business cycles. But that doesn't mean IS-LM isn't a useful starting point -- it just means it's incomplete.

There was a blog discussion with Krugman and a few others a while back about IS-LM, and one point is that for all it's flaws, it has the advantage of (a) actually being a model that makes predictions that are roughly accurate (b) being pretty simple (c) explaining, to an extent, the effects of monetary and fiscal policy in the short run.

I think it’s important to teach the IS-LM model as a starting point, because done right, it makes it clear that what we’re basically doing is the minimal model that has goods, bonds, and money — that there is nothing arbitrary about the whole thing, that this is basically what you have to do if you want a minimal model of the things that matter for short-run macro. Mark reminds me, by the way, that I published a paper on all this (pdf) a decade ago; you know you’re getting old when you don’t remember all the papers you’ve written.

Another point: it is really important, I think, to understand how liquidity preference and loanable funds can both be true at the same time; IS-LM is the way to do that.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/08/ah-yes-lm-wonkish/

RommelDAK

(21 posts)Howdy again, Dan!

With respect to the labor market, while the effect is the same (i.e., extended periods of involuntary unemployment are possible), that the reasons are different is significant. Again, in the IS-LM/Keynesian view, the market works just as perfectly as described by Monetarists, Austrians, and other hard-core free marketers, but there is a monkey wrench in the works: inflexible wages and prices. “Dang,” such economists might say, “if only we could get them to be flexible, our troubles would be over!” This overall philosophy is very important, not only in terms of understanding labor markets but in thinking about policy in general. Such an approach suggests market liberalization as one of the keys to prosperity. Keynesians believe that we need to “interfere” with that otherwise perfect market, but not too much! Thus describes the economics of more progressive Neoclassicals like Krugman. He’s a moderate member of a school of thought that believes that the market is always right.

Meanwhile, Keynes agrees that wages do not adjust, but not because they are inflexible. The latter implies that if only external constraints like minimum wage laws, unions, and implicit contracts didn’t exist, they WOULD fall, that they are just dying to move if not for those artificial impediments in their way. Not so, says Keynes. A perfectly free market with involuntary unemployment is already in equilibrium. The wage isn’t trying to go anywhere. And short of hiring day laborers outside of the local homeless shelter, no industry can costlessly replace their workers every day. Indeed, what is the incentive to go to this trouble if they are already profit maximizing, which is what their being on the labor demand curve implies? Is there any question that firms could have easily replaced workers in this fashion during the Great Depression? And yet, in an environment that was as close to a pure free market as we have ever been, they did not–and workers did not have the choice of going on unemployment back then.

Bottom line: when we have involuntary unemployment, wages are not being stopped from falling as in the IS-LM/Keynesian story, they aren’t even trying. And nor should we want them to, actually, since it has the potential to further lower demand and cause default on those payments that are contracted in nominal terms (house, car, credit cards, etc.–the big ones!!!).

Second, you comment, “But that doesn't mean IS-LM isn't a useful starting point -- it just means it's incomplete.” I disagree. It’s a terrible starting point. What it implies about the determination of interest rates and their effect on investment, for example, is way off base and frames the problem very poorly. Not only are interest rates basically set 100% by the Fed (pegged at a certain level and held there), but firms care relatively little about what rates are in making their investment decision. They are far more concerned with expectations of profit (which is what you’ll read in Keynes’ chapter 22). That appears absolutely nowhere in IS-LM, nor have I ever seen anyone incorporate it. That’s because you really can’t, because you have already used up the axis on which you put the independent variable with one that isn’t all that important (i.e., interest). This is why we have seen the Fed screwing with all this quantitative easing stuff to no avail. That’s not where the problem lies. Firms aren’t dying to invest and are just waiting for interest rates to fall. But that’s the story that arises from IS-LM.

Have you ever seen what Keynes actually laid out instead of IS-LM? His Z-D diagram has expected sales on the vertical axis and employment on the horizontal, and equilibrium arises where expected and realized sales are the same. In Keynes, there is absolutely no reason to believe that that point coincides with full employment. In fact, it probably won’t. Hence, we do not end up with the belief that markets would be perfect if only we could get rid of the various impediments. Rather, they break down regularly and often catastrophically, and government intervention is absolutely necessary.

BTW, this isn’t a bad review of Keynes’ Z-D analysis:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3045303011.html

The Victoria Chick book cited is the absolute best explanation of the General Theory that exists. In fact, I happened to find a reproduction of her Z-D online:

Even then, Z-D suffers from the fact that it’s static. The description in chapter 22 is much more dynamic. Speaking of which, try reading chapter 22 and ask yourself: would I have come up with anything approaching IS-LM to represent it?

Incidentally, here is the article in which John Hicks invented IS-LM (although it’s IS-LL here). I have my intermediate macro students read Keynes’ General Theory and then Hicks’ article. Their reaction is that it’s hard to believe that Hicks read the same book they did!

DanTex

(20,709 posts)Howdy again!

Re: labor market.

I don't take "sticky prices" to mean that prices are sticky because of some external constraint (minimum wage laws, unions), but rather that "downwards nominal rigidity" is an inherent attribute of labor markets: prices are sticky "just 'cause they are" -- nobody knows exactly why, but it is an empirically verifiable phenomenon. There are various theories as to why, but AFAIK, none has won out over the rest. As I see it, there is some kind of implicit cost to cutting wages -- whether it causes demoralized or less productive workers, or damage to a firm's reputation, or anything else, I can't say. And, importantly, the same cost does not apply to cutting real wages -- firms are much more willing to freeze wages in the face of inflation than they are to actually cut wages when there is no inflation.

I don't agree that firms have no incentive to cut wages because they are "already maximizing profit". If a firm can produce the same amount of output, while paying workers less, then it would make more profit. I agree that, empirically, firms don't actually cut wages, or go out and hire cheaper workers, at least not as often as classical theory would imply that they should. But this doesn't mean that they wouldn't be more profitable if they were suddenly able to instantly swap out their current workers with equally productive workers that were being paid less.

Re: IS-LM is a good/terrible starting point.

I think IS-LM does a pretty good job explaining the effects of monetary policy in "normal circumstances". Yes, the Fed sets the interest rate, but they do so by controlling the money supply. More money = lower interest rate = more private investment. And IS-LM also does a pretty good job of describing the effects of fiscal policy, again to a first order approximation.

And, yes, I do think that interest rates do affect firms' decisions to invest or not. Of course, their expectations of profit are also hugely important. If I expect an investment to yield 5% (risk-adjusted), and I can borrow at 4%, I'll do it, but if I can only borrow at 6%, then I won't. IS-LM assumes that profit expectations are fixed in the short run, and are not affected by fiscal and economic policy. You might argue that these assumptions are false, and you would be right, but I would say that they are not so far off as to make IS-LM useless.

Of course, the situation right now is different than a normal recession for a lot of reasons, one of them being that short-term interest rates are at 0. Also, Quantitative Easing doesn't fall easily into the IS-LM framework because IS-LM assumes there is only one interest rate.

Nevertheless, the IS-LM model does in fact do a pretty good job explaining what is going on now, why conventional monetery policy is ineffective, and why increased deficit spending will not raise interest rates or crowd out private investment in the short term. Wikipedia has a good explanation:

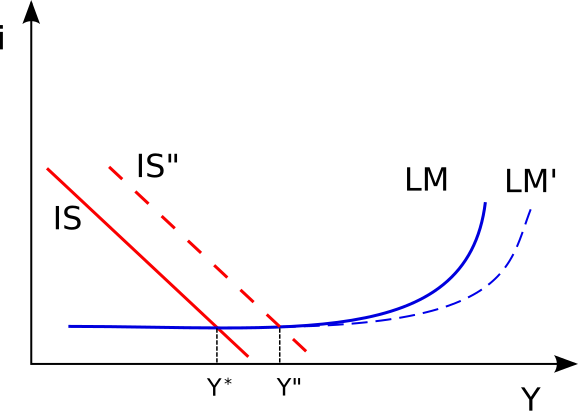

Liquidity trap visualized in a IS-LM diagram. A monetary expansion (the shift from LM to LM') has no effect on equilibrium interest rates or output. However, fiscal expansion (the shift from IS to IS"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquidity_trap

Re: Z-D

I admit I've never seen that before. Will take a look, and also I'll be sure to read chapter 22 of GT when I get the time! Thanks!

Egalitarian Thug

(12,448 posts)How many interpretation of a single economic theory are there?

How many economists are there?

![]()

Wish I could actually help, but I got mine out of some horrible textbooks taught by professors that didn't really understand what they were trying to teach. Thankfully it was not my major.

RommelDAK

(21 posts)Howdy, Dan!

Well, not surprisingly, I don’t agree! But maybe I ought to give some background first.

Keynes didn’t have a degree in econ, it was actually in math (statistics to be exact), but his father was an economist (John Neville Keynes) and a family friend/colleague of John Neville was the premier economist of that age, Alfred Marshall. So Keynes learned from his old man and Marshall, and was basically a mainstream economist at first. He also, incidentally, played the market a lot, and his research in math was on decision making.

Mainstream economics believed/believes that the economy basically takes care of itself. There had been downturns, but they had gone away fairly quickly. And so, when the Great Depression hit (quite a bit earlier in Europe, incidentally), they, including Keynes, figured the same. But, as we all know, that didn’t happen. So what was going on?

While some mainstream economists assured everyone that in the long run, it would be fine, Keynes figured that to be a pretty useless claim. What do we do in the meantime? He was finally able to do what others could not: realize that it was the tools they were using that were wrong and that we needed to throw them out. As he says in the preface to the General Theory:

“The composition of this book has been for the author a long struggle of escape, and so must the reading of it be for most readers if the author’s assault upon them is to be successful,— a struggle of escape from habitual modes of thought and expression. The ideas which are here expressed so laboriously are extremely simple and should be obvious. The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds.”

And so he laid out the theory that I discussed above. In chapter two, he rejects the mainstream labor market as irrelevant because wages aren’t the key issue. Then he zooms in on demand, then investment, then the financial sector, and then the endogeneity of the business cycle as driven by fluctuations in expected profits (or, in his language, the marginal efficiency of capital, or mec). He writes in chapter 22, “...I suggest that the essential character of the Trade Cycle, and, especially, the regularity of time-sequence and of duration which justifies us in calling it a cycle, is mainly due to the way in which the marginal efficiency of capital fluctuates.”. Keynes believed, incidentally, that interest rates played only a very minor role (again from chapter 22):

“Now, we have been accustomed in explaining the “crisis” to lay stress on the rising tendency of the rate of interest under the influence of the increased demand for money both for trade and speculative purposes. At times this factor may certainly play an aggravating and, occasionally perhaps, an initiating part. But I suggest that a more typical, and often the predominant, explanation of the crisis is, not primarily a rise in the rate of interest, but a sudden collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital.”

This was published in 1936.

But then, in 1937, John Hicks writes his article entitled “Mr. Keynes and the Classics: A Suggested Interpretation.” In that paper, Hicks lays out a mainstream (i.e., classical) model and then changes just a very few things and says, “And this is what Keynes said!” And no one ever bothered to read the General Theory again–Hicks’ article was much shorter! An exaggeration, of course, but not much of one. And what Hicks said became Keynesian economics. Meanwhile a small number of scholars tried to keep Keynes’ vision alive. They became the Post Keynesians (which is a strange name for a group that followed Keynes!), a school of thought of which I am a member. With respect to the Keynesians (as opposed to the Post Keynesians), little wonder what they did was so similar to mainstream economics–Hicks created a “Keynes” model using their basic approach and just tacking on a couple of things. N not only is it a long way from Keynes, even Hicks later admitted it and rejected IS-LM.

Returning to our discussion, you write:

“I don't take "sticky prices" to mean that prices are sticky because of some external constraint (minimum wage laws, unions), but rather that "downwards nominal rigidity" is an inherent attribute of labor markets: prices are sticky "just 'cause they are" -- nobody knows exactly why, but it is an empirically verifiable phenomenon.”

That may be what you mean by it, but it’s not what Neoclassical economics says. The Wikipedia entry writes that it boils down to “ menu costs, money illusion, imperfect information with regard to price changes, and fairness concerns.” Each of these could be corrected somehow and are preventing the market from doing what it wants to do, i.e., drive wages down. Keynes’ view is more radical: the market for labor is not really a market in the traditional sense. We cannot apply that same logic to it. Furthermore, declines in wages can lead to a fall in demand and thus an inward movement of the labor demand curve. Such a market, if it were one, would be very unstable. The key is that while the labor demand curve IS a locus of equilibrium points (i.e, the economy must lie on it somewhere), the labor supply curve is not. There is no reason we have to be on it because the unemployment lack of realistic means of making that happen. Even if they offer to work for less, firms aren’t hiring. Speaking of which:

DanTex: “If a firm can produce the same amount of output, while paying workers less, then it would make more profit.”

The labor demand curve is derived from the marginal product of labor curve, meaning that it shows the profit-maximizing level of employment associated with each wage rate. In the model–which is a mainstream model, not Keynes’–firms are satisfied whenever they are on the curve. It is possible that they might earn higher profits at lower wages, assuming everything else stayed equal, but if this is a powerful force in real life, then why don’t we witness it in periods like the Depression, where there were no minimum wage laws, unemployment compensation schemes, or powerful unions? If it doesn’t happen then, when would it happen? The problem again is that at the aggregate level it’s not really a market at all.

Returning to IS-LM, I think it does a very poor job of explaining the economy even in normal times. I’ll expand on that but, would it not be terribly important for it to work well now? Keynes’ does. His works all the time (hence the title General Theory). As I said above, interest rates are an extremely weak force in the real world. Firms just don’t care nearly as much as Keynesians think they do. That means a nearly vertical IS curve. And to mimic what the Fed does, you’d have to put the LM curve horizontal. Basically, you end up with something close to what I saw at the front of the classroom during my twelve years of Catholic school!

Now, with this IS-LM plus sign in front of us, what happens next? Absolutely nothing, unless IS shifts. And in that model, that really only occurs with an exogenous policy change. Meanwhile, even if the Fed targets a new interest rate, it has very little effect. Where is the cyclical breakdown of the economy? Where can we see the involuntary unemployment? How does it show the change in the marginal efficiency of capital over time or the critical interplay between animal spirits and uncertainty? In what sense does IS-LM predict the financial crisis or the Great Depression, or any recession? It’s all gone. All of the really exciting, revolutionary stuff from Keynes has been stripped away, leaving something little more than a slightly more realistic version of a model that sucked in the first place.

Again, I urge you to read that chapter 22, which puts all the pieces together and tries to tell the story of the business cycle, and see how on earth you can make any sense of it using IS-LM. Investment is the key to Keynes’ explanation, and the marginal efficiency of capital is the key to investment.

Whew! Have to get to bed. I apologize in advance for any spelling or grammatical errors or any ambiguities. I usually reread stuff ten times before I post it, but no time tonight!