The U.S. was supposed to leave Afghanistan by 2017. Now it might take decades.

Last edited Tue Jan 26, 2016, 10:26 AM - Edit history (1)

Top U.S. military commanders, who only a few months ago were planning to pull the last American troops out of Afghanistan by year’s end, are now quietly talking about an American commitment that could keep thousands of troops in the country for decades.

The shift in mindset, made possible by President Obama’s decision last fall to cancel withdrawal plans, reflects the Afghan government’s vulnerability to continued militant assault and concern that terror groups like al-Qaeda continue to build training camps whose effect could be felt far beyond the region, said senior military officials.

The military outlook mirrors arguments made by many Republican and Democrat foreign policy advisers, looking beyond the Obama presidency, for a significant long-term American presence.

“This is not a region you want to abandon,” said Michèle Flournoy, a former Pentagon official who would likely be considered a top candidate for Secretary of Defense in a Hillary Clinton administration. “So the question is what do we need going forward given our interests?”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2016/01/26/the-u-s-was-supposed-to-leave-afghanistan-by-2017-now-it-might-take-decades/

Edit: Gee, who could have predicted this?

EdwardBernays

(3,343 posts)The US' foreign policy is sooo insanely muddled that we could stay there for 100 years and it would still be an unsalvageable situation...

unhappycamper

(60,364 posts)The Chance for Peace speech was an address given by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower on April 16, 1953, shortly after the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Speaking only three months into his presidency, Eisenhower likened arms spending to stealing from the people, and evoked William Jennings Bryan in describing "humanity hanging from a cross of iron." Although Eisenhower, a former military man, spoke against increased military spending, the Cold War deepened during his administration and political pressures for increased military spending mounted. By the time he left office in 1961, he felt it necessary to warn of the military-industrial complex.

Background

Eisenhower took office in January 1953, with the Korean War winding down. The Soviet Union had detonated an atomic bomb, and appeared to reach approximate military parity with the United States.[1] Political pressures for a more aggressive stance toward the Soviet Union mounted, and calls for increased military spending did as well. Joseph Stalin's demise on March 5, 1953, briefly left a power vacuum in the Soviet Union and offered a chance for rapprochement with the new regime, as well as an opportunity to decrease military spending.[2]

The Chance for Peace

The speech was addressed to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, in Washington D.C., on April 16, 1953. Eisenhower took an opportunity to highlight the cost of continued tensions and rivalry with the Soviet Union.[3] While addressed to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the speech was broadcast nationwide, through use of television and radio, from the Statler Hotel.[4] He noted that not only were there military dangers (as had been demonstrated by the Korean War), but an arms race would place a huge domestic burden on both nations (see guns and butter):

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. . . . This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.[1][5]

Legacy

Eisenhower's "humanity hanging from a cross of iron" evoked William Jennings Bryan's Cross of Gold speech. As a result, "The Chance for Peace speech", colloquially, became known as the "Cross of Iron speech" and was seen by many as contrasting the Soviet Union’s view of the post-World War II world, with the United States' cooperation and national reunion view.[6]

Despite Eisenhower's hopes as expressed in the speech, the Cold War deepened during his time in office.[7] His farewell address was "a bookend" to his Chance for Peace speech.[1][8] In that speech, he implored Americans to think to the future and "not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow",[9] but the large peacetime military budgets that became established during his administration have continued for half a century.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guns_versus_butter_model

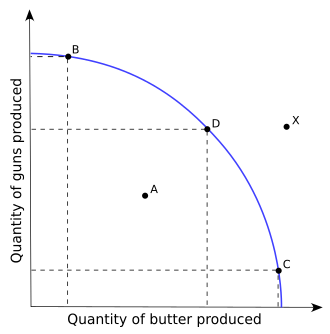

In macroeconomics, the guns versus butter model is an example of a simple production–possibility frontier. It demonstrates the relationship between a nation's investment in defense and civilian goods. In this example, a nation has to choose between two options when spending its finite resources. It may buy either guns (invest in defense/military) or butter (invest in production of goods), or a combination of both. This may be seen as an analogy for choices between defense and civilian spending in more complex economies.

The "guns or butter" model is used generally as a simplification of national spending as a part of GDP. The nation will have to decide which balance of guns versus butter best fulfills its needs, with its choice being partly influenced by the military spending and military stance of potential opponents. Researchers in political economy have viewed the trade-off between military and consumer spending as a useful predictor of election success.[1]

The production possibilities frontier for guns versus butter. Points like X are impossible to achieve, while the barely achievable B, C, and D illustrate the tradeoff between guns and butter: at these levels of production, producing more of one requires producing less of the other.

Origin of the term

One theory on the origin of the concept comes from William Jennings Bryan's resignation as United States Secretary of State in the Wilson Administration.[2] At the outbreak of World War I, the leading global exporter of nitrates for gunpowder was Chile. Chile had maintained neutrality during the war and provided nearly all of the USA's nitrate requirements. It also was the principal ingredient of chemical fertilizer in farming.[3] The export product was sodium nitrate, a salt mined in the northern part of Chile that often is referred to as Chile saltpeter.

With substantial popular opinion running against U.S. entry into the war, the Bryan resignation and peace campaign (joined prominently with Henry Ford's efforts) became a banner for local versus national interests. Bryan was no more pro-German than Wilson; his motivation was to expose and publicize what he considered to be an unconscionable public policy.

The National Defense Act of 1916 directed the president to select a site for the artificial production of nitrates within the United States. It was not until September 1917, several months after the USA entered the war, that Wilson selected Muscle Shoals, Alabama, after more than a year of competition among political rivals. A deadlock in Congress was broken when Senator Ellison D. Smith from South Carolina sponsored the National Defense Act of 1916 that directed "the Secretary of Agriculture to manufacture nitrates for fertilizers in peace and munitions in war at water power sites designated by the President". This was presented by the news media as "guns and butter".

Origin of the term

One theory on the origin of the concept comes from William Jennings Bryan's resignation as United States Secretary of State in the Wilson Administration.[2] At the outbreak of World War I, the leading global exporter of nitrates for gunpowder was Chile. Chile had maintained neutrality during the war and provided nearly all of the USA's nitrate requirements. It also was the principal ingredient of chemical fertilizer in farming.[3] The export product was sodium nitrate, a salt mined in the northern part of Chile that often is referred to as Chile saltpeter.

With substantial popular opinion running against U.S. entry into the war, the Bryan resignation and peace campaign (joined prominently with Henry Ford's efforts) became a banner for local versus national interests. Bryan was no more pro-German than Wilson; his motivation was to expose and publicize what he considered to be an unconscionable public policy.

The National Defense Act of 1916 directed the president to select a site for the artificial production of nitrates within the United States. It was not until September 1917, several months after the USA entered the war, that Wilson selected Muscle Shoals, Alabama, after more than a year of competition among political rivals. A deadlock in Congress was broken when Senator Ellison D. Smith from South Carolina sponsored the National Defense Act of 1916 that directed "the Secretary of Agriculture to manufacture nitrates for fertilizers in peace and munitions in war at water power sites designated by the President". This was presented by the news media as "guns and butter".

Quoted use of term

Perhaps the best known use of the phrase (in translation) was in Nazi Germany. In a speech on January 17, 1936, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels stated: "We can do without butter, but, despite all our love of peace, not without arms. One cannot shoot with butter, but with guns." Referencing the same concept, sometime in the summer of the same year another Nazi official, Hermann Göring, announced in a speech, "Guns will make us powerful; butter will only make us fat."[4]

While president of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson used the phrase to catch the attention of the national media while reporting on the state of national defense and the economy.[5]

Another use of the phrase was British prime minister Margaret Thatcher's reference in a 1976 speech that, "The Soviets put guns over butter, but we put almost everything over guns."[6]

The song "Guns Before Butter" by Gang of Four from their 1979 album Entertainment! is about this concept.

Prodigy's 1997 album The Fat Of The Land has the following text on the fold-out booklet: "We have no butter, but I ask you /Would you rather have butter or guns? /Shall we import lard or steel? Let me tell you /Preparedness makes us powerful. /Butter merely makes us fat."[7]

This phrase as the title for an episode ("Guns Not Butter"

Great Society example

United States President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society programs in the 1960s are examples of the guns versus butter model. While Johnson wanted to continue New Deal programs and expand welfare with his own Great Society programs, he also was in the arms race of the Cold War, and Vietnam War. These wars put strains on the economy and hampered his Great Society programs.[citation needed]

This is in stark contrast to Dwight D Eisenhower's own objections to the expansion and endless warfare of the military industrial complex. In his Chance for Peace speech, he referred to this very trade-off, giving specific examples:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.

The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter plane with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people.

This is, I repeat, the best way of life to be found on the road the world has been taking. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron. ... Is there no other way the world may live?

—?Speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors "The Chance for Peace" (16 April 1953)