Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

August 16, 2019

59 Years Ago Today; Joe Kittinger's Giant Leap from 102,000 ft

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Kittinger

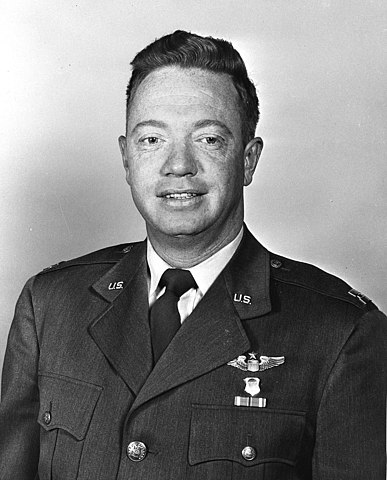

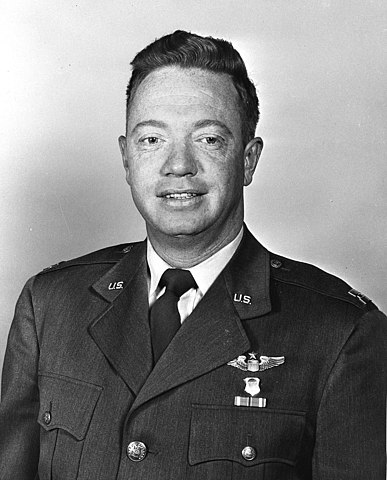

Colonel Joseph W. Kittinger II, USAF (pictured as a captain)

Joseph William Kittinger II (born July 27, 1928) is a retired colonel in the United States Air Force and a USAF Command Pilot. His initial operational assignment was in fighter aircraft, then he participated in Project Manhigh and Project Excelsior high altitude balloon flight projects from 1956 to 1960, setting a world record for the highest skydive from a height greater than 19 miles (31 km). He was also the first man to make a solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in a gas balloon, and the first man to fully witness the curvature of the earth.

Kittinger served as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War, and he achieved an aerial kill of a North Vietnamese MiG-21 jet fighter and was later shot down himself, spending 11 months as a prisoner of war in a North Vietnamese prison. He participated in the Red Bull Stratos project as capsule communicator in 2012 at age 84, directing Felix Baumgartner on his record-breaking 24-mile (39 km) freefall from Earth's stratosphere.

Early life and military career

Born in Tampa, Florida, and raised in Orlando, Florida, Kittinger was educated at The Bolles School in Jacksonville, Florida, and the University of Florida. He became fascinated with planes at a very young age and soloed in a Piper Cub by the time he was 17. After racing speedboats as a teenager, he entered the U.S. Air Force as an aviation cadet in March 1949. On completion of aviation cadet training in March 1950, he received his pilot wings and a commission as a second lieutenant. He was subsequently assigned to the 86th Fighter-Bomber Wing based at Ramstein Air Base in West Germany, flying the F-84 Thunderjet and F-86 Sabre.

In 1954 Kittinger was transferred to the Air Force Missile Development Center (AFMDC) at Holloman AFB, New Mexico. It was during this assignment that he flew the observation/chase plane that monitored flight surgeon Colonel John Stapp's rocket sled run of 632 mph (1,017 km/h) in 1955. Kittinger was impressed by Stapp's dedication and leadership as a pioneer in aerospace medicine. Stapp, in turn, was impressed with Kittinger's skillful jet piloting, later recommending him for space-related aviation research work. Stapp was to foster the high-altitude balloon tests that would later lead to Kittinger's record-setting leap from over 102,800 feet (31,300 m). In 1957, as part of Project Manhigh, Kittinger set an interim balloon altitude record of 96,760 feet (29,490 m) in Manhigh I, for which he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross.

Project Excelsior

Kittinger next to the Excelsior gondola

Captain Kittinger was next assigned to the Aerospace Medical Research Laboratories at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio. For Project Excelsior (meaning "ever upward" ), a name given to the project by Colonel Stapp as part of research into high-altitude bailouts, he made a series of three extreme altitude parachute jumps from an open gondola carried aloft by large helium balloons. These jumps were made in a "rocking-chair" position, descending on his back, rather than in the usual face-down position familiar to skydivers. This was because he was wearing a 60 lb (27 kg) "kit" on his behind, and his pressure suit naturally formed a sitting shape when it was inflated, a shape appropriate for sitting in an airplane cockpit.

Excelsior I: Kittinger's first high-altitude jump, from about 76,400 feet (23,300 m) on November 16, 1959, was a near-disaster when an equipment malfunction caused him to lose consciousness. The automatic parachute opener in his equipment saved his life. He went into a flat spin at a rotational velocity of about 120 rpm, the g-forces at his extremities having been calculated to be over 22 times the force of gravity, setting another record.

Excelsior II: On December 11, 1959, Kittinger jumped again from about 74,700 feet (22,800 m). For this leap, he was awarded the A. Leo Stevens Parachute Medal.

Kittinger's record-breaking skydive from Excelsior III

Excelsior III: On August 16, 1960, Kittinger made the final high-altitude jump at 102,800 feet (31,300 m). Towing a small drogue parachute for initial stabilization, he fell for 4 minutes and 36 seconds, reaching a maximum speed of 614 miles per hour (988 km/h)

before opening his parachute at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Incurring yet another equipment malfunction, the pressurization for his right glove malfunctioned during the ascent and his right hand swelled to twice its normal size, but he rode the balloon up to 102,800 feet before stepping off.

Of the jumps from Excelsior, Kittinger said:

Kittinger set historical numbers for highest balloon ascent, highest parachute jump, longest-duration drogue-fall (four minutes), and fastest speed by a human being through the atmosphere. These were the USAF records, but were not submitted for aerospace world records to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Kittinger's record for the highest ascent was broken in 1961 by Malcolm Ross and Victor Prather. His records for highest parachute jump and fastest velocity stood for 52 years, until they were broken in 2012 by Felix Baumgartner.

For this series of jumps, Kittinger was profiled in Life magazine and the National Geographic Magazine, decorated with a second Distinguished Flying Cross, and awarded the Harmon Trophy by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Project Stargazer

Back at Holloman Air Force Base, Kittinger took part in Project Stargazer on December 13–14, 1962. He and the astronomer William C. White took an open-gondola helium balloon packed with scientific equipment to an altitude of about 82,200 feet (25,100 m), where they spent over 18 hours performing astronomical observations.

Later USAF career

In 1965, after returning to the operational air force, Kittinger was approached by civilian amateur parachutist Nick Piantanida for assistance on Pintandia's Strato Jump project, an effort to break the previous freefall records of both Kittinger and Soviet Air Force officer Yevgeni Andreyev. Kittinger refused to participate in the effort, believing Piantanida's approach to the project was too reckless. Piantanida was subsequently killed in 1966 during his Strato Jump III attempt.

Kittinger later served three combat tours of duty during the Vietnam War, flying a total of 483 combat missions. During his first two tours he flew as an aircraft commander in Douglas A-26 Invaders and modified On Mark Engineering B-26K Counter-Invaders as part of Operations Farm Gate and Big Eagle.

Following his first two Vietnam tours, he returned to the United States and soon transitioned to the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II. During a voluntary third tour of duty to Vietnam in 1971–72, he commanded the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron (555 TFS), the noted "Triple Nickel" squadron, flying the F-4D Phantom II. During this period he was credited with shooting down a North Vietnamese MiG-21 while flying an F-4D, USAF Serial No. 66-7463, with his WSO, 1st Lieutenant Leigh Hodgdon.

Kittinger was shot down on May 11, 1972, just before the end of his third tour of duty. While flying an F-4D, USAF Serial No. 66-0230, with his weapons systems officer, 1st Lieutenant William J. Reich, Lieutenant Colonel Kittinger was leading a flight of Phantoms approximately five miles northwest of Thai Nguyen, North Vietnam, when they were engaged by a flight of enemy MiG-21 fighters. Kittinger and his wingman were chasing a MiG-21 when Kittinger's Phantom II was hit by an air-to-air missile from another MiG-21 that damaged the Phantom's starboard wing and set the aircraft on fire. Kittinger and Reich ejected a few miles from Thai Nguyen and were soon captured and taken to the city of Hanoi. During the same engagement, Kittinger's wingman, Captain S. E. Nichols, shot down the MiG-21 they had been chasing.

Kittinger and Reich spent 11 months as prisoners of war (POWs) in the Hỏa Lò Prison, the so-called "Hanoi Hilton". Kittinger was put through rope torture soon after his arrival at the POW compound and this made a lasting impression on him. Kittinger was the senior ranking officer (SRO) among the newer prisoners of war, i.e., those captured after 1969. In Kittinger's autobiography "Come Up and Get Me" (by Kittinger and Craig Ryan), Kittinger emphasized being very serious about maintaining the military structure he considered essential to survival. Kittinger and Reich were returned to American hands during Operation Homecoming on March 28, 1973, and they continued their air force careers, with Kittinger having been promoted to full colonel while in captivity. Following his return, Colonel Kittinger attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama.

Following completion of the Air War College, Kittinger became the vice commander of the 48th Tactical Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath, United Kingdom, where he again flew the F-4 Phantom II. In 1977, he transferred to Headquarters, 12th Air Force, at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, retiring from the air force in 1978.

Kittinger accumulated 7,679 flying hours in the air force, including 948 combat flying hours during three tours during the Vietnam War. In addition, he has flown over 9,100 hours in various civilian aircraft.

<snip>

Later civilian career

Kittinger retired from the air force as a colonel in 1978 and initially went to work for Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) Corporation in Orlando, Florida. He later became vice president of flight operations for Rosie O'Grady's Flying Circus, part of the Rosie O'Grady's/Church Street Station entertainment complex in Orlando, prior to the parent company's dissolution.

Still interested in ballooning, he set a gas balloon world distance record for the AA-06 size class (since broken) of 3,221.23 km in 1983. He then completed the first solo balloon crossing of the Atlantic in the 106,000 cubic foot (3,000 m³) Balloon of Peace, from September 14 to September 18, 1984, organized by the Canadian promoter Gaetan Croteau. As an official FAI world aerospace record, it is the longest gas balloon distance flight ever recorded in the AA-10 size category (5,703.03 km). For the second time in his life, he was also the subject of a story in National Geographic Magazine.

Kittinger also participated in the Gordon Bennett Cup in ballooning in 1989 (ranked third) and 1994 (ranked 12th).

In the early 1990s, Kittinger played a lead role with NASA assisting Charles "Nish" Bruce to break his highest parachute jump record. The project was suspended in 1994.

Joining the Red Bull Stratos project, Kittinger advised Felix Baumgartner on Baumgartner's October 14, 2012 free-fall from 128,100 feet (39,045m). The project collected leading experts in the fields of aeronautics, medicine and engineering to ensure its success. Kittinger eventually served as CAPCOM (capsule communicator) for Baumgartner's jump, which exceeded the altitude of Kittinger's previous jump during Project Excelsior.

As of 2013, Kittinger has been assisting balloonist Jonathan Trappe's attempt to be the first to cross the Atlantic by cluster balloon.

</snip>

Colonel Joseph W. Kittinger II, USAF (pictured as a captain)

Joseph William Kittinger II (born July 27, 1928) is a retired colonel in the United States Air Force and a USAF Command Pilot. His initial operational assignment was in fighter aircraft, then he participated in Project Manhigh and Project Excelsior high altitude balloon flight projects from 1956 to 1960, setting a world record for the highest skydive from a height greater than 19 miles (31 km). He was also the first man to make a solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in a gas balloon, and the first man to fully witness the curvature of the earth.

Kittinger served as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War, and he achieved an aerial kill of a North Vietnamese MiG-21 jet fighter and was later shot down himself, spending 11 months as a prisoner of war in a North Vietnamese prison. He participated in the Red Bull Stratos project as capsule communicator in 2012 at age 84, directing Felix Baumgartner on his record-breaking 24-mile (39 km) freefall from Earth's stratosphere.

Early life and military career

Born in Tampa, Florida, and raised in Orlando, Florida, Kittinger was educated at The Bolles School in Jacksonville, Florida, and the University of Florida. He became fascinated with planes at a very young age and soloed in a Piper Cub by the time he was 17. After racing speedboats as a teenager, he entered the U.S. Air Force as an aviation cadet in March 1949. On completion of aviation cadet training in March 1950, he received his pilot wings and a commission as a second lieutenant. He was subsequently assigned to the 86th Fighter-Bomber Wing based at Ramstein Air Base in West Germany, flying the F-84 Thunderjet and F-86 Sabre.

In 1954 Kittinger was transferred to the Air Force Missile Development Center (AFMDC) at Holloman AFB, New Mexico. It was during this assignment that he flew the observation/chase plane that monitored flight surgeon Colonel John Stapp's rocket sled run of 632 mph (1,017 km/h) in 1955. Kittinger was impressed by Stapp's dedication and leadership as a pioneer in aerospace medicine. Stapp, in turn, was impressed with Kittinger's skillful jet piloting, later recommending him for space-related aviation research work. Stapp was to foster the high-altitude balloon tests that would later lead to Kittinger's record-setting leap from over 102,800 feet (31,300 m). In 1957, as part of Project Manhigh, Kittinger set an interim balloon altitude record of 96,760 feet (29,490 m) in Manhigh I, for which he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross.

Project Excelsior

Kittinger next to the Excelsior gondola

Captain Kittinger was next assigned to the Aerospace Medical Research Laboratories at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio. For Project Excelsior (meaning "ever upward" ), a name given to the project by Colonel Stapp as part of research into high-altitude bailouts, he made a series of three extreme altitude parachute jumps from an open gondola carried aloft by large helium balloons. These jumps were made in a "rocking-chair" position, descending on his back, rather than in the usual face-down position familiar to skydivers. This was because he was wearing a 60 lb (27 kg) "kit" on his behind, and his pressure suit naturally formed a sitting shape when it was inflated, a shape appropriate for sitting in an airplane cockpit.

Excelsior I: Kittinger's first high-altitude jump, from about 76,400 feet (23,300 m) on November 16, 1959, was a near-disaster when an equipment malfunction caused him to lose consciousness. The automatic parachute opener in his equipment saved his life. He went into a flat spin at a rotational velocity of about 120 rpm, the g-forces at his extremities having been calculated to be over 22 times the force of gravity, setting another record.

Excelsior II: On December 11, 1959, Kittinger jumped again from about 74,700 feet (22,800 m). For this leap, he was awarded the A. Leo Stevens Parachute Medal.

Kittinger's record-breaking skydive from Excelsior III

Excelsior III: On August 16, 1960, Kittinger made the final high-altitude jump at 102,800 feet (31,300 m). Towing a small drogue parachute for initial stabilization, he fell for 4 minutes and 36 seconds, reaching a maximum speed of 614 miles per hour (988 km/h)

before opening his parachute at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Incurring yet another equipment malfunction, the pressurization for his right glove malfunctioned during the ascent and his right hand swelled to twice its normal size, but he rode the balloon up to 102,800 feet before stepping off.

Lord, take care of me now.

— Kittinger, jumping from the balloon gondola Excelsior III at 102,800 feet

Of the jumps from Excelsior, Kittinger said:

There's no way you can visualize the speed. There's nothing you can see to see how fast you're going. You have no depth perception. If you're in a car driving down the road and you close your eyes, you have no idea what your speed is. It's the same thing if you're free falling from space. There are no signposts. You know you are going very fast, but you don't feel it. You don't have a 614-mph wind blowing on you. I could only hear myself breathing in the helmet.

Kittinger set historical numbers for highest balloon ascent, highest parachute jump, longest-duration drogue-fall (four minutes), and fastest speed by a human being through the atmosphere. These were the USAF records, but were not submitted for aerospace world records to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Kittinger's record for the highest ascent was broken in 1961 by Malcolm Ross and Victor Prather. His records for highest parachute jump and fastest velocity stood for 52 years, until they were broken in 2012 by Felix Baumgartner.

For this series of jumps, Kittinger was profiled in Life magazine and the National Geographic Magazine, decorated with a second Distinguished Flying Cross, and awarded the Harmon Trophy by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Project Stargazer

Back at Holloman Air Force Base, Kittinger took part in Project Stargazer on December 13–14, 1962. He and the astronomer William C. White took an open-gondola helium balloon packed with scientific equipment to an altitude of about 82,200 feet (25,100 m), where they spent over 18 hours performing astronomical observations.

Later USAF career

In 1965, after returning to the operational air force, Kittinger was approached by civilian amateur parachutist Nick Piantanida for assistance on Pintandia's Strato Jump project, an effort to break the previous freefall records of both Kittinger and Soviet Air Force officer Yevgeni Andreyev. Kittinger refused to participate in the effort, believing Piantanida's approach to the project was too reckless. Piantanida was subsequently killed in 1966 during his Strato Jump III attempt.

Kittinger later served three combat tours of duty during the Vietnam War, flying a total of 483 combat missions. During his first two tours he flew as an aircraft commander in Douglas A-26 Invaders and modified On Mark Engineering B-26K Counter-Invaders as part of Operations Farm Gate and Big Eagle.

Following his first two Vietnam tours, he returned to the United States and soon transitioned to the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II. During a voluntary third tour of duty to Vietnam in 1971–72, he commanded the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron (555 TFS), the noted "Triple Nickel" squadron, flying the F-4D Phantom II. During this period he was credited with shooting down a North Vietnamese MiG-21 while flying an F-4D, USAF Serial No. 66-7463, with his WSO, 1st Lieutenant Leigh Hodgdon.

Kittinger was shot down on May 11, 1972, just before the end of his third tour of duty. While flying an F-4D, USAF Serial No. 66-0230, with his weapons systems officer, 1st Lieutenant William J. Reich, Lieutenant Colonel Kittinger was leading a flight of Phantoms approximately five miles northwest of Thai Nguyen, North Vietnam, when they were engaged by a flight of enemy MiG-21 fighters. Kittinger and his wingman were chasing a MiG-21 when Kittinger's Phantom II was hit by an air-to-air missile from another MiG-21 that damaged the Phantom's starboard wing and set the aircraft on fire. Kittinger and Reich ejected a few miles from Thai Nguyen and were soon captured and taken to the city of Hanoi. During the same engagement, Kittinger's wingman, Captain S. E. Nichols, shot down the MiG-21 they had been chasing.

Kittinger and Reich spent 11 months as prisoners of war (POWs) in the Hỏa Lò Prison, the so-called "Hanoi Hilton". Kittinger was put through rope torture soon after his arrival at the POW compound and this made a lasting impression on him. Kittinger was the senior ranking officer (SRO) among the newer prisoners of war, i.e., those captured after 1969. In Kittinger's autobiography "Come Up and Get Me" (by Kittinger and Craig Ryan), Kittinger emphasized being very serious about maintaining the military structure he considered essential to survival. Kittinger and Reich were returned to American hands during Operation Homecoming on March 28, 1973, and they continued their air force careers, with Kittinger having been promoted to full colonel while in captivity. Following his return, Colonel Kittinger attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama.

Following completion of the Air War College, Kittinger became the vice commander of the 48th Tactical Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath, United Kingdom, where he again flew the F-4 Phantom II. In 1977, he transferred to Headquarters, 12th Air Force, at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, retiring from the air force in 1978.

Kittinger accumulated 7,679 flying hours in the air force, including 948 combat flying hours during three tours during the Vietnam War. In addition, he has flown over 9,100 hours in various civilian aircraft.

<snip>

Later civilian career

Kittinger retired from the air force as a colonel in 1978 and initially went to work for Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) Corporation in Orlando, Florida. He later became vice president of flight operations for Rosie O'Grady's Flying Circus, part of the Rosie O'Grady's/Church Street Station entertainment complex in Orlando, prior to the parent company's dissolution.

Still interested in ballooning, he set a gas balloon world distance record for the AA-06 size class (since broken) of 3,221.23 km in 1983. He then completed the first solo balloon crossing of the Atlantic in the 106,000 cubic foot (3,000 m³) Balloon of Peace, from September 14 to September 18, 1984, organized by the Canadian promoter Gaetan Croteau. As an official FAI world aerospace record, it is the longest gas balloon distance flight ever recorded in the AA-10 size category (5,703.03 km). For the second time in his life, he was also the subject of a story in National Geographic Magazine.

Kittinger also participated in the Gordon Bennett Cup in ballooning in 1989 (ranked third) and 1994 (ranked 12th).

In the early 1990s, Kittinger played a lead role with NASA assisting Charles "Nish" Bruce to break his highest parachute jump record. The project was suspended in 1994.

Joining the Red Bull Stratos project, Kittinger advised Felix Baumgartner on Baumgartner's October 14, 2012 free-fall from 128,100 feet (39,045m). The project collected leading experts in the fields of aeronautics, medicine and engineering to ensure its success. Kittinger eventually served as CAPCOM (capsule communicator) for Baumgartner's jump, which exceeded the altitude of Kittinger's previous jump during Project Excelsior.

As of 2013, Kittinger has been assisting balloonist Jonathan Trappe's attempt to be the first to cross the Atlantic by cluster balloon.

</snip>

August 16, 2019

92 Years Ago Today; Dole Air Race from San Francisco to Honolulu - only 2 out of 8 planes finish

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dole_Air_Race

The Dole Air Race, also known as the Dole Derby, was a tragic air race across the Pacific Ocean from northern California to the Territory of Hawaii in August 1927. Of the 15–18 airplanes entered, eleven were certified to compete but three crashed before the race, resulting in three deaths. Eight eventually participated in the race, with two crashing on takeoff and two going missing during the race. A third, forced to return for repairs, took off again to search for the missing and was itself never seen again. In all, before, during, and after the race, ten lives were lost and six airplanes were total losses. Two of the eight planes successfully landed in Hawaii.

The Dole prize

James D Dole

Inspired by Charles A. Lindbergh's successful trans-Atlantic flight, James D. Dole, the Hawaii pineapple magnate, put up a prize of US$25,000 for the first fixed-wing aircraft to fly the 3,870 kilometers (2,405 mi) from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii, and US$10,000 for second place.

The transpacific record

The first transpacific flight had already taken place, twice over. On 28 June, about a month after Dole posted the prizes, Air Corps Lieutenants Lester J. Maitland and Albert F. Hegenberger flew a three-engine Atlantic-Fokker C-2 military aircraft from Oakland Municipal Airport to Wheeler Army Airfield on Oahu in 25 hours and 50 minutes. Ernie Smith and Captain C.H. Carter had arrived earlier for the attempt, but due to mechanical difficulties, took off two hours after Maitland, and returned with a broken windshield. Carter quit after the record was lost, but Smith hired Emory Bronte as a navigator, and the City of Oakland, a small Travel Air 5000 civilian monoplane, took off again on July 14. Upon running out of fuel 26 hours and 36 minutes later, they crash-landed in a thorn tree on Molokai. Dole disqualified both of them from his prizes because they did not land in Honolulu (the Air Corps flight had been planned months prior to the prize announcement and had no intent to land other than at Wheeler).

The Dole Air Derby

The draw started at the Matson Building.

An early entrant was Richard Grace, a Hollywood stunt pilot who shipped his plane to San Francisco shortly after wrecking his Cruzair in a Kauai to San Francisco attempt in June. The draw for starting position in the Dole race was held on 8 August in the office of C. W. Saunders, California director of the National Aeronautics Association, in the Matson Building in San Francisco.

Two days after the draw, United States Navy Lieutenants George W. D. Covell and R. S. Waggener took off from San Diego, California in their Tremaine Humming Bird Spirit of John Rodgers to fly to Oakland, flew into a fog bank, crashed into an ocean cliff at Point Loma, and died. The next day, British pilot Arthur V. Rogers took off for a test flight in the twin engine Angel of Los Angeles at Western Air Express Field at Montebello, California, circled, came about to land, jumping out of the plane before it suddenly dived into the ground, and died.

Mildred Doran

Meanwhile, Mildred Doran, Auggy Pedlar, and navigator Manley Lawling were flying into Oakland when their aircraft developed engine trouble. They successfully landed in a wheat field in the San Joaquin Valley, but had trouble making repairs because they no longer had any tools. Doran was quoted as stating, "We threw [the tools] off at Long Beach because they were in the way and cluttering things up." Lawling was later replaced by Vilas R. Knope when Lawling could not satisfy the race committee of his navigational skills. He reportedly got lost over Oakland.

Then, on 11 August, as J. L. Giffin and Theodore S. Lundgren approached Oakland, their aircraft, an International CF-10 Triplane, the Pride of Los Angeles, crashed into San Francisco Bay, but the two men were unhurt.

In test flights before the race, Gobel's Woolaroc encountered gear issues that required Gobel to hang outside the plane to fix. The Air King (City of Peoria) flown by Charles Parkhurst Lomax and Ralph C. Lower Jr, was disqualified on the 16th because its 370-gallon tanks were estimated to give the plane a range 300 miles short by inspectors. A missing component on the Miss Doran compass sparked fears of vandalism the night before the flight.

Participants

The race began on 16 August, by which time the starting line-up had diminished to eight aircraft:

Pabco Flyer, a Breese-Wilde Monoplane, NX646, flown alone by Livingston Gilson Irving

Woolaroc, One of two modified Travel Air 5000 aircraft, NX869, flown by Arthur C. Goebel and navigated by William V. Davis Jr.

Oklahoma, a Travel Air 5000 sister ship of Woolaroc, NX911, piloted by Bennett Griffin and navigated by Al Henley

Aloha, a Breese-Wilde 5 Monoplane, NX914, flown by Martin Jensen and navigated by Paul Schluter

El Encanto, a Goddard Special metal monoplane, NX5074, flown by Norman A. Goddard and Kenneth C. Hawkins, which was heavily favored in the pre-race odds

Golden Eagle, the prototype Lockheed Vega 1 monoplane, NX913, flown by Jack Frost and navigated by Gordon Scott

Miss Doran, a Buhl CA-5 Air Sedan, NC2915, flown by Auggy Pedlar, navigated by Vilas R. Knope, and carrying Mildred Doran

Dallas Spirit, a Swallow Monoplane, NX941, flown by William Portwood Erwin and navigated by Alvin Eichwaldt

Takeoff, race and aftermath

The fifteen competitors were seen off by a crowd estimated to include 75,000 to 100,000 persons. Weather was predicted to have a high fog on takeoff and showers along the route.

The initial takeoffs were plagued with trouble. Oklahoma took off first just before 11am. The crew would eventually abort the flight over San Francisco with an overheating engine. She was followed by El Encanto, which failed to clear the runway before she swerved and crashed. Pabco Flyer lifted momentarily into the air, then crashed some 7000 feet from the runway. Their crews were not hurt. Golden Eagle took off smoothly and flew out of sight. Miss Doran succeeded in taking off but circled back and landed less than ten minutes later, its engine “sputtering like a Tin Lizzie.” Then Dallas Spirit returned to Oakland with fabric ripping off the fuselage. Aloha and Woolaroc took off uneventfully, and Miss Doran succeeded on her second attempt. Pabco Flyer also tried and crashed a second time.

Frontpage of the San Francisco Chronicle, 18 August 1927

Woolaroc flew a great-circle route, flying at 4,000 to 6,000 feet of altitude. The navigator Davis used sextants and smoke bombs to calculate course and wind drift. They were greeted in Hawaii and escorted by a Boeing PW-9 out of Wheeler Field. Goebel and Davis won the race in 26 hours, 17 minutes, earning them the US$25,000 first prize. Aloha arrived in 28 hours, 16 minutes, earning Jensen and Schluter the US$10,000 second prize. Out of his $10,000 winnings, pilot Jensen gave his navigator Schulter only $25. Neither Golden Eagle nor Miss Doran was ever seen again.

The search for the Golden Eagle and Miss Doran was aided by three submarines, USS R-8, USS S-42, and USS S-46. After repairing Dallas Spirit, Erwin and Eichwaldt joined the search, leaving Oakland for Honolulu. Their last radio message was that they were in a spin. Neither was seen again. In the days after the race, the disqualified owners of the Air King charged that race officials should have disqualified the Golden Eagle, because it also had only 350 gallons of fuel capacity when it took off. In a bitter conclusion, the father of the sponsor of the race, Rev. Charles F. Dole, died on November 27, 1927.

Goebel and Davis returned on a Matson liner to an impromptu parade in San Francisco where they doubted there would be any survivors of a sea ditching. Woolaroc has survived and is on display at the Woolaroc Museum in Oklahoma, which started as a hangar to store and display the plane.

</snip>

The Dole Air Race, also known as the Dole Derby, was a tragic air race across the Pacific Ocean from northern California to the Territory of Hawaii in August 1927. Of the 15–18 airplanes entered, eleven were certified to compete but three crashed before the race, resulting in three deaths. Eight eventually participated in the race, with two crashing on takeoff and two going missing during the race. A third, forced to return for repairs, took off again to search for the missing and was itself never seen again. In all, before, during, and after the race, ten lives were lost and six airplanes were total losses. Two of the eight planes successfully landed in Hawaii.

The Dole prize

James D Dole

Inspired by Charles A. Lindbergh's successful trans-Atlantic flight, James D. Dole, the Hawaii pineapple magnate, put up a prize of US$25,000 for the first fixed-wing aircraft to fly the 3,870 kilometers (2,405 mi) from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii, and US$10,000 for second place.

The transpacific record

The first transpacific flight had already taken place, twice over. On 28 June, about a month after Dole posted the prizes, Air Corps Lieutenants Lester J. Maitland and Albert F. Hegenberger flew a three-engine Atlantic-Fokker C-2 military aircraft from Oakland Municipal Airport to Wheeler Army Airfield on Oahu in 25 hours and 50 minutes. Ernie Smith and Captain C.H. Carter had arrived earlier for the attempt, but due to mechanical difficulties, took off two hours after Maitland, and returned with a broken windshield. Carter quit after the record was lost, but Smith hired Emory Bronte as a navigator, and the City of Oakland, a small Travel Air 5000 civilian monoplane, took off again on July 14. Upon running out of fuel 26 hours and 36 minutes later, they crash-landed in a thorn tree on Molokai. Dole disqualified both of them from his prizes because they did not land in Honolulu (the Air Corps flight had been planned months prior to the prize announcement and had no intent to land other than at Wheeler).

The Dole Air Derby

The draw started at the Matson Building.

An early entrant was Richard Grace, a Hollywood stunt pilot who shipped his plane to San Francisco shortly after wrecking his Cruzair in a Kauai to San Francisco attempt in June. The draw for starting position in the Dole race was held on 8 August in the office of C. W. Saunders, California director of the National Aeronautics Association, in the Matson Building in San Francisco.

Two days after the draw, United States Navy Lieutenants George W. D. Covell and R. S. Waggener took off from San Diego, California in their Tremaine Humming Bird Spirit of John Rodgers to fly to Oakland, flew into a fog bank, crashed into an ocean cliff at Point Loma, and died. The next day, British pilot Arthur V. Rogers took off for a test flight in the twin engine Angel of Los Angeles at Western Air Express Field at Montebello, California, circled, came about to land, jumping out of the plane before it suddenly dived into the ground, and died.

Mildred Doran

Meanwhile, Mildred Doran, Auggy Pedlar, and navigator Manley Lawling were flying into Oakland when their aircraft developed engine trouble. They successfully landed in a wheat field in the San Joaquin Valley, but had trouble making repairs because they no longer had any tools. Doran was quoted as stating, "We threw [the tools] off at Long Beach because they were in the way and cluttering things up." Lawling was later replaced by Vilas R. Knope when Lawling could not satisfy the race committee of his navigational skills. He reportedly got lost over Oakland.

Then, on 11 August, as J. L. Giffin and Theodore S. Lundgren approached Oakland, their aircraft, an International CF-10 Triplane, the Pride of Los Angeles, crashed into San Francisco Bay, but the two men were unhurt.

In test flights before the race, Gobel's Woolaroc encountered gear issues that required Gobel to hang outside the plane to fix. The Air King (City of Peoria) flown by Charles Parkhurst Lomax and Ralph C. Lower Jr, was disqualified on the 16th because its 370-gallon tanks were estimated to give the plane a range 300 miles short by inspectors. A missing component on the Miss Doran compass sparked fears of vandalism the night before the flight.

Participants

The race began on 16 August, by which time the starting line-up had diminished to eight aircraft:

Pabco Flyer, a Breese-Wilde Monoplane, NX646, flown alone by Livingston Gilson Irving

Woolaroc, One of two modified Travel Air 5000 aircraft, NX869, flown by Arthur C. Goebel and navigated by William V. Davis Jr.

Oklahoma, a Travel Air 5000 sister ship of Woolaroc, NX911, piloted by Bennett Griffin and navigated by Al Henley

Aloha, a Breese-Wilde 5 Monoplane, NX914, flown by Martin Jensen and navigated by Paul Schluter

El Encanto, a Goddard Special metal monoplane, NX5074, flown by Norman A. Goddard and Kenneth C. Hawkins, which was heavily favored in the pre-race odds

Golden Eagle, the prototype Lockheed Vega 1 monoplane, NX913, flown by Jack Frost and navigated by Gordon Scott

Miss Doran, a Buhl CA-5 Air Sedan, NC2915, flown by Auggy Pedlar, navigated by Vilas R. Knope, and carrying Mildred Doran

Dallas Spirit, a Swallow Monoplane, NX941, flown by William Portwood Erwin and navigated by Alvin Eichwaldt

Takeoff, race and aftermath

The fifteen competitors were seen off by a crowd estimated to include 75,000 to 100,000 persons. Weather was predicted to have a high fog on takeoff and showers along the route.

The initial takeoffs were plagued with trouble. Oklahoma took off first just before 11am. The crew would eventually abort the flight over San Francisco with an overheating engine. She was followed by El Encanto, which failed to clear the runway before she swerved and crashed. Pabco Flyer lifted momentarily into the air, then crashed some 7000 feet from the runway. Their crews were not hurt. Golden Eagle took off smoothly and flew out of sight. Miss Doran succeeded in taking off but circled back and landed less than ten minutes later, its engine “sputtering like a Tin Lizzie.” Then Dallas Spirit returned to Oakland with fabric ripping off the fuselage. Aloha and Woolaroc took off uneventfully, and Miss Doran succeeded on her second attempt. Pabco Flyer also tried and crashed a second time.

Frontpage of the San Francisco Chronicle, 18 August 1927

Woolaroc flew a great-circle route, flying at 4,000 to 6,000 feet of altitude. The navigator Davis used sextants and smoke bombs to calculate course and wind drift. They were greeted in Hawaii and escorted by a Boeing PW-9 out of Wheeler Field. Goebel and Davis won the race in 26 hours, 17 minutes, earning them the US$25,000 first prize. Aloha arrived in 28 hours, 16 minutes, earning Jensen and Schluter the US$10,000 second prize. Out of his $10,000 winnings, pilot Jensen gave his navigator Schulter only $25. Neither Golden Eagle nor Miss Doran was ever seen again.

The search for the Golden Eagle and Miss Doran was aided by three submarines, USS R-8, USS S-42, and USS S-46. After repairing Dallas Spirit, Erwin and Eichwaldt joined the search, leaving Oakland for Honolulu. Their last radio message was that they were in a spin. Neither was seen again. In the days after the race, the disqualified owners of the Air King charged that race officials should have disqualified the Golden Eagle, because it also had only 350 gallons of fuel capacity when it took off. In a bitter conclusion, the father of the sponsor of the race, Rev. Charles F. Dole, died on November 27, 1927.

Goebel and Davis returned on a Matson liner to an impromptu parade in San Francisco where they doubted there would be any survivors of a sea ditching. Woolaroc has survived and is on display at the Woolaroc Museum in Oklahoma, which started as a hangar to store and display the plane.

</snip>

August 16, 2019

99 Years Ago Today; Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Indians killed by pitch to head

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_Chapman

Raymond Johnson Chapman (January 15, 1891 – August 17, 1920) was an American baseball player, spending his entire career as a shortstop for the Cleveland Indians.

Chapman was hit in the head by a pitch thrown by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays, and died 12 hours later. He remains the only Major League Baseball player to have died from an injury received during an MLB game. His death led to Major League Baseball establishing a rule requiring umpires to replace the ball whenever it became dirty, and it was partially the reason—along with sanitary concerns—that the spitball was banned after the 1920 season. Chapman's death was also one of the examples used to emphasize the need for wearing batting helmets (although the rule requiring their use was not adopted until over 30 years later).

Death

At the time of Chapman's death, part of every pitcher's job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field. By turns, they smeared it with dirt, licorice, and tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred, cut, and spiked. The result was a "misshapen, earth-colored ball that traveled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and, as it came over the plate, was very hard to see."

This practice is believed to have contributed to Chapman's death. He was struck with a pitch by Carl Mays on August 16, 1920, in a game against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Mays threw with a submarine delivery, and it was the top of the fifth inning, in the late afternoon. Eyewitnesses recounted that Chapman never moved out of the way of the pitch, presumably unable to see the ball. "Chapman didn't react at all," said Rod Nelson of the Society for American Baseball Research. "It was at twilight and it froze him." The sound of the ball smashing into Chapman's skull was so loud that Mays thought it had hit the end of Chapman's bat, so he fielded the ball and threw to first base.

Mike Sowell, in his book The Pitch That Killed, states that first baseman Wally Pipp caught Mays's throw to first and then realized something was very wrong. Chapman never took any steps, but rather slowly collapsed to his knees and then to the ground with blood pouring out of his left ear. Umpire Tommy Connolly quickly called for doctors in the stands to come to Chapman's aid. Eventually Chapman was able to stand and to try to walk off the field, but mumbled when he attempted to speak. As he was walking off the field, his knees buckled and he had to be assisted the rest of the way. He was replaced by Harry Lunte for the rest of the game, which the Indians won 4–3. Chapman died 12 hours later in a New York City hospital, at about 4:30 a.m.

Thousands of mourners were present for Chapman's funeral at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in Cleveland. In tribute to Chapman's memory, Cleveland players wore black armbands, with manager Tris Speaker leading the team to win both the pennant and the first World Series championship in the history of the club. Rookie Joe Sewell took Chapman's place at shortstop, and went on to have a Hall of Fame career (which he coincidentally concluded with the Yankees).

Ray Chapman's grave

Ray Chapman is buried at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio, not far from where his new home was being built on Alvason Road in East Cleveland. He and his wife had visited the home as it was being built several hours before he departed for New York on his final road trip.

Honors

Restored Chapman plaque at Heritage Park in Progressive Field

Not long after Chapman died, a bronze plaque was designed in his honor, funded by donations from fans. The plaque features Chapman's bust framed by a baseball diamond and flanked by two bats, one of which is draped with a fielder's mitt. At the bottom of the tablet is the inscription, "He lives in the hearts of all who knew him". The plaque was dedicated and hung at League Park and was moved to Cleveland Stadium in 1946 when the Indians moved to that stadium. Sometime in the early 1970s, however, it was taken down for unknown reasons.

The plaque was rediscovered while the Indians were moving from Cleveland Stadium to Jacobs Field after the 1993 season. Jim Folk, the Indians' vice president of ballpark operations, said, "It was in a store room under an escalator in a little nook and cranny. We didn't know what we were going to do with it, but there was no way it was just going to stay there when we moved to Jacobs Field. We had it crated up and put on a moving truck and it came over along with our file cabinets and all the other stuff that came out of the stadium." After the move, it was lost and forgotten once again. "It just kind of got forgotten about, to be honest," Folk said.

In February 2007, workers discovered the plaque while cleaning out a storage room at Progressive Field. Covered by thirteen years of dust and dirt, the bronze surface had oxidized a dark brown and the text was illegible. The plaque was refurbished and made part of Heritage Park at Progressive Field, an area that opened soon after in April 2007 and includes the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame and other exhibits from the team's history. Chapman had previously been inducted into the team hall of fame in July 2006, part of the first new induction class since 1972.

</snip>

Raymond Johnson Chapman (January 15, 1891 – August 17, 1920) was an American baseball player, spending his entire career as a shortstop for the Cleveland Indians.

Chapman was hit in the head by a pitch thrown by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays, and died 12 hours later. He remains the only Major League Baseball player to have died from an injury received during an MLB game. His death led to Major League Baseball establishing a rule requiring umpires to replace the ball whenever it became dirty, and it was partially the reason—along with sanitary concerns—that the spitball was banned after the 1920 season. Chapman's death was also one of the examples used to emphasize the need for wearing batting helmets (although the rule requiring their use was not adopted until over 30 years later).

Death

At the time of Chapman's death, part of every pitcher's job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field. By turns, they smeared it with dirt, licorice, and tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred, cut, and spiked. The result was a "misshapen, earth-colored ball that traveled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and, as it came over the plate, was very hard to see."

This practice is believed to have contributed to Chapman's death. He was struck with a pitch by Carl Mays on August 16, 1920, in a game against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Mays threw with a submarine delivery, and it was the top of the fifth inning, in the late afternoon. Eyewitnesses recounted that Chapman never moved out of the way of the pitch, presumably unable to see the ball. "Chapman didn't react at all," said Rod Nelson of the Society for American Baseball Research. "It was at twilight and it froze him." The sound of the ball smashing into Chapman's skull was so loud that Mays thought it had hit the end of Chapman's bat, so he fielded the ball and threw to first base.

Mike Sowell, in his book The Pitch That Killed, states that first baseman Wally Pipp caught Mays's throw to first and then realized something was very wrong. Chapman never took any steps, but rather slowly collapsed to his knees and then to the ground with blood pouring out of his left ear. Umpire Tommy Connolly quickly called for doctors in the stands to come to Chapman's aid. Eventually Chapman was able to stand and to try to walk off the field, but mumbled when he attempted to speak. As he was walking off the field, his knees buckled and he had to be assisted the rest of the way. He was replaced by Harry Lunte for the rest of the game, which the Indians won 4–3. Chapman died 12 hours later in a New York City hospital, at about 4:30 a.m.

Thousands of mourners were present for Chapman's funeral at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in Cleveland. In tribute to Chapman's memory, Cleveland players wore black armbands, with manager Tris Speaker leading the team to win both the pennant and the first World Series championship in the history of the club. Rookie Joe Sewell took Chapman's place at shortstop, and went on to have a Hall of Fame career (which he coincidentally concluded with the Yankees).

Ray Chapman's grave

Ray Chapman is buried at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio, not far from where his new home was being built on Alvason Road in East Cleveland. He and his wife had visited the home as it was being built several hours before he departed for New York on his final road trip.

Honors

Restored Chapman plaque at Heritage Park in Progressive Field

Not long after Chapman died, a bronze plaque was designed in his honor, funded by donations from fans. The plaque features Chapman's bust framed by a baseball diamond and flanked by two bats, one of which is draped with a fielder's mitt. At the bottom of the tablet is the inscription, "He lives in the hearts of all who knew him". The plaque was dedicated and hung at League Park and was moved to Cleveland Stadium in 1946 when the Indians moved to that stadium. Sometime in the early 1970s, however, it was taken down for unknown reasons.

The plaque was rediscovered while the Indians were moving from Cleveland Stadium to Jacobs Field after the 1993 season. Jim Folk, the Indians' vice president of ballpark operations, said, "It was in a store room under an escalator in a little nook and cranny. We didn't know what we were going to do with it, but there was no way it was just going to stay there when we moved to Jacobs Field. We had it crated up and put on a moving truck and it came over along with our file cabinets and all the other stuff that came out of the stadium." After the move, it was lost and forgotten once again. "It just kind of got forgotten about, to be honest," Folk said.

In February 2007, workers discovered the plaque while cleaning out a storage room at Progressive Field. Covered by thirteen years of dust and dirt, the bronze surface had oxidized a dark brown and the text was illegible. The plaque was refurbished and made part of Heritage Park at Progressive Field, an area that opened soon after in April 2007 and includes the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame and other exhibits from the team's history. Chapman had previously been inducted into the team hall of fame in July 2006, part of the first new induction class since 1972.

</snip>

August 15, 2019

P.S. In the eighties, I called that combo "Saturday Night". Never did shoot anything up...

Dayton shooter had cocaine, other drugs in system

https://abc6onyourside.com/news/local/coroner-dayton-gunman-had-drugs-and-alcohol-in-his-system

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The Montgomery County coroner says the Dayton gunman had cocaine and other drugs in his system at the time of the massing shooting that killed nine people before police fatally shot him.

Dr. Kent Harshbarger said during a Thursday news conference that authorities also found a bag of cocaine on the body of 24-year-old Connor Betts. He also said the gunman was shot 24 to 26 times. The Police Chief said he tried to get up twice after being hit by the officers.

</snip>

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The Montgomery County coroner says the Dayton gunman had cocaine and other drugs in his system at the time of the massing shooting that killed nine people before police fatally shot him.

Dr. Kent Harshbarger said during a Thursday news conference that authorities also found a bag of cocaine on the body of 24-year-old Connor Betts. He also said the gunman was shot 24 to 26 times. The Police Chief said he tried to get up twice after being hit by the officers.

</snip>

P.S. In the eighties, I called that combo "Saturday Night". Never did shoot anything up...

August 15, 2019

Good on ol' Max!!

Good on ol' Max!!

50 Years Ago Today: Max Yasgur's farm becomes one of the most populous places in NYS

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Yasgur

Max Yasgur at the Woodstock Festival in 1969 which was held on part of his dairy farm in Bethel, New York

Max B. Yasgur (December 15, 1919 – February 9, 1973) was an American farmer, best known as the owner of the dairy farm in Bethel, New York, at which the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was held between August 15 and August 18, 1969.

Personal life and dairy farming

Yasgur was born in New York City to Russian Jewish immigrants Samuel and Bella Yasgur. He was raised with his brother Isidore (1926-2010) on the family's farm (where his parents also ran a small hotel) and attended New York University, studying real estate law. By the late 1960s, he was the largest milk producer in Sullivan County, New York. His farm had 650 cows, mostly Guernseys.

Max Yasgur's dairy farm in 1968

At the time of the festival in 1969, Yasgur was married to Miriam (Mimi) Gertrude Miller Yasgur (1920–2014) and had a son, Sam (1942–2016) and daughter Lois (1944–1977). His son was an assistant district attorney in New York City at the time.

In later years, it was revealed that Yasgur was in fact a conservative Republican who supported the Vietnam War. Nevertheless, he felt that the Woodstock festival could help business at his farm and also tame the generation gap. Despite claims that he showed disapproval towards the treatment of the counterculture movement, this has not been confirmed. Woodstock promoter Michael Lang, who considered Yasgur to be his "hero," stated that Yasgur was in fact "the antithesis" of what the Woodstock festival stood for. Yasgur's early death prevented him from answering questions about why the festival took place.

Woodstock Festival

After area villages Saugerties (located about 40 miles (64 km) from Yasgur's farm) and Wallkill declined to provide a venue for the festival, Yasgur leased one of his farm's fields for a fee that festival sponsors said was $10,000.[4] Soon afterward he began to receive both threatening and supporting phone calls (which could not be placed without the assistance of an operator because the community of White Lake, New York, where the telephone exchange was located, still utilized manual switching). Some of the calls threatened to burn him out. However, the helpful calls outnumbered the threatening ones. Opposition to the festival began soon after the festival's relocation to Bethel was announced. Signs were erected around town, saying, "Local People Speak Out Stop Max's Hippie Music Festival. No 150,000 hippies here" and "Buy no milk"

Yasgur was 49 at the time of the festival and had a heart condition. He said at the time that he never expected the festival to be so large, but that "if the generation gap is to be closed, we older people have to do more than we have done."

Yasgur quickly established a rapport with the concert-goers, providing food at cost or for free. When he heard that some local residents were reportedly selling water to people coming to the concert, he put up a big sign at his barn on New York State Route 17B reading "Free Water." The New York Times reported that Yasgur "slammed a work-hardened fist on the table and demanded of some friends, 'How can anyone ask money for water?'" His son Sam recalled his father telling his children to "take every empty milk bottle from the plant, fill them with water and give them to the kids, and give away all the milk and milk products we had at the dairy."

At the time of the concert, friends described Yasgur as an individualist who was motivated as much by his principles as by the money. According to Sam Yasgur, his father agreed to rent the field to the festival organizers because it was a very wet year, which curtailed hay production. The income from the rental would offset the cost of purchasing thousands of bales of hay.

Yasgur also believed strongly in freedom of expression, and was angered by the hostility of some townspeople toward "anti-war hippies". Hosting the festival became, for him, a "cause".

On the second day of the festival, just before Joe Cocker's early afternoon set, Yasgur addressed the crowd.

After Woodstock

Many of his neighbors turned against him after the festival, and he was no longer welcome at the town general store, but he never regretted his decision to allow the concert on his farm. On January 7, 1970, he was sued by his neighbors for property damage caused by the concert attendees. However, the damage to his own property was far more extensive and, over a year later, he received a $50,000 settlement to pay for the near-destruction of his dairy farm.[citation needed] He refused to rent out his farm for a 1970 revival of the festival, saying, "As far as I know, I'm going back to running a dairy farm."

In 1971, Yasgur sold the 600-acre (2.4 km2) farm, and moved to Marathon, Florida, where, a year and a half later, he died of a heart attack at the age of 53. He was given a full-page obituary in Rolling Stone magazine, one of the few non-musicians to have received such an honor.

In 1997, the site of the concert and 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) surrounding it was purchased by Alan Gerry for the purpose of creating the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. In August 2007, the 103-acre (0.42 km2) parcel that contains Yasgur's former homestead, about 3 miles from the festival site, was placed on the market for $8 million by its owner, Roy Howard.

In popular culture

Joni Mitchell's song "Woodstock" (also covered by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Matthews Southern Comfort, Richie Havens, James Taylor, Eva Cassidy, and Brooke Fraser) refers to "Yasgur's Farm".

In addition, Mountain (who were also at the festival) recorded a song shortly after the event entitled "For Yasgur's Farm".

The band Moon Safari has a song titled "Yasgur's Farm" on their album Blomljud.

Yasgur is portrayed by Eugene Levy in Ang Lee's film Taking Woodstock.

Sam Yasgur wrote a book about his father, Max B. Yasgur: The Woodstock Festival's Famous Farmer, in August 2009.

Quotes

</snip>

Max Yasgur at the Woodstock Festival in 1969 which was held on part of his dairy farm in Bethel, New York

Max B. Yasgur (December 15, 1919 – February 9, 1973) was an American farmer, best known as the owner of the dairy farm in Bethel, New York, at which the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was held between August 15 and August 18, 1969.

Personal life and dairy farming

Yasgur was born in New York City to Russian Jewish immigrants Samuel and Bella Yasgur. He was raised with his brother Isidore (1926-2010) on the family's farm (where his parents also ran a small hotel) and attended New York University, studying real estate law. By the late 1960s, he was the largest milk producer in Sullivan County, New York. His farm had 650 cows, mostly Guernseys.

Max Yasgur's dairy farm in 1968

At the time of the festival in 1969, Yasgur was married to Miriam (Mimi) Gertrude Miller Yasgur (1920–2014) and had a son, Sam (1942–2016) and daughter Lois (1944–1977). His son was an assistant district attorney in New York City at the time.

In later years, it was revealed that Yasgur was in fact a conservative Republican who supported the Vietnam War. Nevertheless, he felt that the Woodstock festival could help business at his farm and also tame the generation gap. Despite claims that he showed disapproval towards the treatment of the counterculture movement, this has not been confirmed. Woodstock promoter Michael Lang, who considered Yasgur to be his "hero," stated that Yasgur was in fact "the antithesis" of what the Woodstock festival stood for. Yasgur's early death prevented him from answering questions about why the festival took place.

Woodstock Festival

After area villages Saugerties (located about 40 miles (64 km) from Yasgur's farm) and Wallkill declined to provide a venue for the festival, Yasgur leased one of his farm's fields for a fee that festival sponsors said was $10,000.[4] Soon afterward he began to receive both threatening and supporting phone calls (which could not be placed without the assistance of an operator because the community of White Lake, New York, where the telephone exchange was located, still utilized manual switching). Some of the calls threatened to burn him out. However, the helpful calls outnumbered the threatening ones. Opposition to the festival began soon after the festival's relocation to Bethel was announced. Signs were erected around town, saying, "Local People Speak Out Stop Max's Hippie Music Festival. No 150,000 hippies here" and "Buy no milk"

Yasgur was 49 at the time of the festival and had a heart condition. He said at the time that he never expected the festival to be so large, but that "if the generation gap is to be closed, we older people have to do more than we have done."

Yasgur quickly established a rapport with the concert-goers, providing food at cost or for free. When he heard that some local residents were reportedly selling water to people coming to the concert, he put up a big sign at his barn on New York State Route 17B reading "Free Water." The New York Times reported that Yasgur "slammed a work-hardened fist on the table and demanded of some friends, 'How can anyone ask money for water?'" His son Sam recalled his father telling his children to "take every empty milk bottle from the plant, fill them with water and give them to the kids, and give away all the milk and milk products we had at the dairy."

At the time of the concert, friends described Yasgur as an individualist who was motivated as much by his principles as by the money. According to Sam Yasgur, his father agreed to rent the field to the festival organizers because it was a very wet year, which curtailed hay production. The income from the rental would offset the cost of purchasing thousands of bales of hay.

Yasgur also believed strongly in freedom of expression, and was angered by the hostility of some townspeople toward "anti-war hippies". Hosting the festival became, for him, a "cause".

On the second day of the festival, just before Joe Cocker's early afternoon set, Yasgur addressed the crowd.

After Woodstock

Many of his neighbors turned against him after the festival, and he was no longer welcome at the town general store, but he never regretted his decision to allow the concert on his farm. On January 7, 1970, he was sued by his neighbors for property damage caused by the concert attendees. However, the damage to his own property was far more extensive and, over a year later, he received a $50,000 settlement to pay for the near-destruction of his dairy farm.[citation needed] He refused to rent out his farm for a 1970 revival of the festival, saying, "As far as I know, I'm going back to running a dairy farm."

In 1971, Yasgur sold the 600-acre (2.4 km2) farm, and moved to Marathon, Florida, where, a year and a half later, he died of a heart attack at the age of 53. He was given a full-page obituary in Rolling Stone magazine, one of the few non-musicians to have received such an honor.

In 1997, the site of the concert and 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) surrounding it was purchased by Alan Gerry for the purpose of creating the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. In August 2007, the 103-acre (0.42 km2) parcel that contains Yasgur's former homestead, about 3 miles from the festival site, was placed on the market for $8 million by its owner, Roy Howard.

In popular culture

Joni Mitchell's song "Woodstock" (also covered by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Matthews Southern Comfort, Richie Havens, James Taylor, Eva Cassidy, and Brooke Fraser) refers to "Yasgur's Farm".

In addition, Mountain (who were also at the festival) recorded a song shortly after the event entitled "For Yasgur's Farm".

The band Moon Safari has a song titled "Yasgur's Farm" on their album Blomljud.

Yasgur is portrayed by Eugene Levy in Ang Lee's film Taking Woodstock.

Sam Yasgur wrote a book about his father, Max B. Yasgur: The Woodstock Festival's Famous Farmer, in August 2009.

Quotes

I hear you are considering changing the zoning law to prevent the festival. I hear you don't like the look of the kids who are working at the site. I hear you don't like their lifestyle. I hear you don't like they are against the war and that they say so very loudly. . . I don't particularly like the looks of some of those kids either. I don't particularly like their lifestyle, especially the drugs and free love. And I don't like what some of them are saying about our government. However, if I know my American history, tens of thousands of Americans in uniform gave their lives in war after war just so those kids would have the freedom to do exactly what they are doing. That's what this country is all about and I am not going to let you throw them out of our town just because you don't like their dress or their hair or the way they live or what they believe. This is America and they are going to have their festival.

—?addressing a Bethel town board prior to the festival.

I'm a farmer. I don't know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world--not only to the Town of Bethel, or Sullivan County, or New York State; you've proven something to the world. This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that, you've had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food, and so forth. Your producers have done a mammoth job to see that you're taken care of... they'd enjoy a vote of thanks. But above that, the important thing that you've proven to the world is that a half a million kids--and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you--a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I God bless you for it!

—?addressing the crowd at Woodstock on August 17, 1969

I made a deal with (Woodstock producer) Mike Lang before the festival started. If anything went wrong I was going to give him a crew cut. If everything was OK I was going to let my hair grow long. I guess he won the bet, but I'm so bald I'll never be able to pay it off.

—?Life magazine, Special Edition, Woodstock 1969

</snip>

August 15, 2019

54 Years Ago Today; The Beatles at Shea Stadium!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beatles%27_1965_US_tour

The Beatles staged their second concert tour of the United States (with one date in Canada) in the late summer of 1965. At the peak of American Beatlemania, they played a mixture of outdoor stadiums and indoor arenas, with historic concerts at Shea Stadium in New York and the Hollywood Bowl. Typically of the era, the tour was a "package" presentation, with several artists on the bill. The Beatles played for just 30 minutes at each show, following sets by support acts such as Brenda Holloway and the King Curtis Band, Cannibal & the Headhunters, and Sounds Incorporated.

After the tour's conclusion, the Beatles took a six-week break before reconvening in mid-October to record the album Rubber Soul.

Background

Brian Epstein, the Beatles' manager, scheduled the band's second full concert tour of America after a series of early-summer concerts in Europe. The group began rehearsing for the tour in London on 25 July, four days before attending the royal premiere of their second feature film, Help! The rehearsals doubled as preparation for their live performance on ABC Television's Blackpool Night Out and took place at the Saville Theatre on 30 July, and then at the ABC Theatre in Blackpool.

Typically for the 1960s, the concerts were arranged in a package-tour format, with multiple acts on the bill. The support acts throughout the tour were Brenda Holloway and the King Curtis Band, Cannibal & the Headhunters, and Sounds Incorporated. The Beatles entourage comprised road managers Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, Epstein, press officer Tony Barrow, and Alf Bicknell, who usually worked as the band's chauffeur. In his autobiography, Barrow recalls that a major part of the advance publicity for the tour was ensuring that interviews the individual Beatles gave to British publications were widely syndicated in the US. He adds that this was easily achieved, given the band's huge international popularity.

Shea Stadium concert

The opening show, at Shea Stadium in the New York borough of Queens, on 15 August was record-breaking and one of the most famous concert events of its era. It set records for attendance and revenue generation. Promoter Sid Bernstein said, "Over 55,000 people saw the Beatles at Shea Stadium. We took $304,000, the greatest gross ever in the history of show business." It remained the highest concert attendance in the United States until 1973, when Led Zeppelin played to an audience of 56,000 in Tampa, Florida. This demonstrated that outdoor concerts on a large scale could be successful and profitable. The Beatles received $160,000 for their performance, which equated to $100 for each second they were on stage. For this concert, the Young Rascals, a New York band championed by Bernstein, were added to the bill.

The Beatles were transported to the rooftop Port Authority Heliport at the World's Fair by a New York Airways Boeing Vertol 107-II helicopter, then took a Wells Fargo armoured truck to Shea Stadium. Two thousand security personnel were at the venue to handle crowd control. The crowd was confined to the spectator areas of the stadium, with nobody other than the band members, their entourage, and security personnel allowed on the field. As a result of this, the audience was a long distance away from the band while they played on a small stage in the middle of the field.

"Beatlemania" was at one of its highest marks at the Shea Concert. Film footage taken at the concert shows many teenagers and women crying, screaming, and even fainting. The crowd noise was such that security guards can be seen covering their ears as the Beatles enter the field. Despite the heavy security presence individual fans broke onto the field a number of times during the concert and had to be chased down and restrained. Concert film footage also shows John Lennon light-heartedly pointing out one such incident as he attempted to talk to the audience in between songs.

The deafening level of crowd noise, coupled with the distance between the band and the audience, meant that nobody in the stadium could hear much of anything. Vox had specially designed 100-watt amplifiers for this tour; however, it was still not anywhere near loud enough, so the Beatles used the house amplification system. Lennon described the noise as "wild" and also twice as deafening when the Beatles performed. On-stage "fold-back" speakers were not in common use in 1965, rendering the Beatles' playing inaudible to each other, forcing them to just play through a list of songs nervously, not knowing what kind of sound was being produced, or whether they were playing in unison. The Beatles section of the concert was extremely short by modern standards (just 30 minutes) but was the typical 1965 Beatles tour set list, with Starr opting to sing "Act Naturally" instead of "I Wanna Be Your Man". Referring to the enormity of the 1965 concert, Lennon later told Bernstein: "You know, Sid, at Shea Stadium I saw the top of the mountain." Barrow described it as "the ultimate pinnacle of Beatlemania" and "the group's brightly-shining summer solstice". The concert was attended by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones and their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham. Afterwards, the Beatles spent the evening and part of the next day socialising with Bob Dylan in their suite in the Warwick Hotel.

</snip>

The Beatles staged their second concert tour of the United States (with one date in Canada) in the late summer of 1965. At the peak of American Beatlemania, they played a mixture of outdoor stadiums and indoor arenas, with historic concerts at Shea Stadium in New York and the Hollywood Bowl. Typically of the era, the tour was a "package" presentation, with several artists on the bill. The Beatles played for just 30 minutes at each show, following sets by support acts such as Brenda Holloway and the King Curtis Band, Cannibal & the Headhunters, and Sounds Incorporated.

After the tour's conclusion, the Beatles took a six-week break before reconvening in mid-October to record the album Rubber Soul.

Background

Brian Epstein, the Beatles' manager, scheduled the band's second full concert tour of America after a series of early-summer concerts in Europe. The group began rehearsing for the tour in London on 25 July, four days before attending the royal premiere of their second feature film, Help! The rehearsals doubled as preparation for their live performance on ABC Television's Blackpool Night Out and took place at the Saville Theatre on 30 July, and then at the ABC Theatre in Blackpool.

Typically for the 1960s, the concerts were arranged in a package-tour format, with multiple acts on the bill. The support acts throughout the tour were Brenda Holloway and the King Curtis Band, Cannibal & the Headhunters, and Sounds Incorporated. The Beatles entourage comprised road managers Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, Epstein, press officer Tony Barrow, and Alf Bicknell, who usually worked as the band's chauffeur. In his autobiography, Barrow recalls that a major part of the advance publicity for the tour was ensuring that interviews the individual Beatles gave to British publications were widely syndicated in the US. He adds that this was easily achieved, given the band's huge international popularity.

Shea Stadium concert

The opening show, at Shea Stadium in the New York borough of Queens, on 15 August was record-breaking and one of the most famous concert events of its era. It set records for attendance and revenue generation. Promoter Sid Bernstein said, "Over 55,000 people saw the Beatles at Shea Stadium. We took $304,000, the greatest gross ever in the history of show business." It remained the highest concert attendance in the United States until 1973, when Led Zeppelin played to an audience of 56,000 in Tampa, Florida. This demonstrated that outdoor concerts on a large scale could be successful and profitable. The Beatles received $160,000 for their performance, which equated to $100 for each second they were on stage. For this concert, the Young Rascals, a New York band championed by Bernstein, were added to the bill.

The Beatles were transported to the rooftop Port Authority Heliport at the World's Fair by a New York Airways Boeing Vertol 107-II helicopter, then took a Wells Fargo armoured truck to Shea Stadium. Two thousand security personnel were at the venue to handle crowd control. The crowd was confined to the spectator areas of the stadium, with nobody other than the band members, their entourage, and security personnel allowed on the field. As a result of this, the audience was a long distance away from the band while they played on a small stage in the middle of the field.

"Beatlemania" was at one of its highest marks at the Shea Concert. Film footage taken at the concert shows many teenagers and women crying, screaming, and even fainting. The crowd noise was such that security guards can be seen covering their ears as the Beatles enter the field. Despite the heavy security presence individual fans broke onto the field a number of times during the concert and had to be chased down and restrained. Concert film footage also shows John Lennon light-heartedly pointing out one such incident as he attempted to talk to the audience in between songs.

The deafening level of crowd noise, coupled with the distance between the band and the audience, meant that nobody in the stadium could hear much of anything. Vox had specially designed 100-watt amplifiers for this tour; however, it was still not anywhere near loud enough, so the Beatles used the house amplification system. Lennon described the noise as "wild" and also twice as deafening when the Beatles performed. On-stage "fold-back" speakers were not in common use in 1965, rendering the Beatles' playing inaudible to each other, forcing them to just play through a list of songs nervously, not knowing what kind of sound was being produced, or whether they were playing in unison. The Beatles section of the concert was extremely short by modern standards (just 30 minutes) but was the typical 1965 Beatles tour set list, with Starr opting to sing "Act Naturally" instead of "I Wanna Be Your Man". Referring to the enormity of the 1965 concert, Lennon later told Bernstein: "You know, Sid, at Shea Stadium I saw the top of the mountain." Barrow described it as "the ultimate pinnacle of Beatlemania" and "the group's brightly-shining summer solstice". The concert was attended by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones and their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham. Afterwards, the Beatles spent the evening and part of the next day socialising with Bob Dylan in their suite in the Warwick Hotel.

</snip>

August 15, 2019

80 Years Ago Today; The premiere of The Wizard of Oz at Grauman's Chinese Theatre

https://tinyurl.com/jcn3suo (Wikipedia link)

The Wizard of Oz is a 1939 American musical fantasy film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Widely considered to be one of the greatest films in cinema history, it is the best-known and most commercially successful adaptation of L. Frank Baum's 1900 children's book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Directed primarily by Victor Fleming (who left production to take over the troubled production of Gone with the Wind), the film stars Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale alongside Ray Bolger, Jack Haley and Bert Lahr.

Characterized by its legendary use of Technicolor (although not being the first to use it), fantasy storytelling, musical score, and memorable characters, the film has become an icon of American popular culture. It was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, but lost to Gone with the Wind, also directed by Fleming. It did win in two other categories: Best Original Song for "Over the Rainbow" and Best Original Score by Herbert Stothart. While the film was considered a critical success upon release in August 1939, it failed to make a profit for MGM until the 1949 re-release, earning only $3,017,000 on a $2,777,000 budget, not including promotional costs, which made it MGM's most expensive production at that time.

The 1956 television broadcast premiere of the film on the CBS network reintroduced the film to the public; according to the Library of Congress, it is the most seen film in movie history. It was among the first 25 films that inaugurated the National Film Registry list in 1989. It is also one of the few films on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. The film is among the top ten in the BFI (British Film Institute) list of 50 films to be seen by the age of 14.