Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal

Dennis Donovan's Journal

August 12, 2019

75 Years Ago Today; Waffen-SS troops massacre 560 people in Sant'Anna di Stazzema.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sant%27Anna_di_Stazzema_massacre

List of the victims

The Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre was a Nazi German war crime committed in the hill village of Sant'Anna di Stazzema in Tuscany, Italy, in the course of an operation against the Italian resistance movement during the Italian Campaign of World War II. On 12 August 1944 the Waffen-SS, with the help of the Brigate Nere, murdered about 560 local villagers and refugees, including more than a hundred children, and burned their bodies. These crimes have been defined as voluntary and organized acts of terrorism by the Military Tribunal of La Spezia and the highest Italian court of appeal.

Massacre

On the morning of 12 August 1944, German troops of the 2nd Battalion of SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 35 of 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS, commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Anton Galler, entered the mountain village of Sant'Anna di Stazzema. With them came some fascists of the 36th Brigata Nera Benito Mussolini based in Lucca, dressed in German uniforms.

The soldiers immediately proceeded to round up villagers and refugees, locking up hundreds of them in several barns and stables, before systematically executing them. The killings were done mostly by shooting groups of people with machine guns or by herding them into basements and other enclosed spaces and tossing in hand grenades. At the 16th-century local church, the priest Fiore Menguzzo (awarded the Medal for Civil Valor posthumously in 1999) was shot at point-blank range, after which machine guns were then turned on some 100 people gathered there. In all, the victims included at least 107 children (the youngest of whom, Anna Pardini, was only 20 days old), as well as eight pregnant women (one of whom, Evelina Berretti, had her stomach cut with a bayonet and her baby pulled out and killed separately).

The restored village church and World War I memorial in 2008

After other people were killed through the village, their corpses were set on fire (at the church, the soldiers used its pews for a bonfire to dispose of the bodies). The livestock were also exterminated and the whole village was burnt down. All this took three hours. The SS men then sat down outside the burning Sant'Anna and ate lunch.

Aftermath

The National Park of Peace monument in 2007

After the war, the church was rebuilt. The Charnel House Monument and the Historical Museum of Resistance were both built nearby. Stations of the Cross illustrate scenes from the massacre along the trail from the church to the main memorial site—the National Park of Peace, founded in 2000. The massacre inspired the novel Miracle at St. Anna by James McBride, and Spike Lee's film of the same title that was based on it.

Prosecutions

Apart from the divisional commander Max Simon,[a] no one was prosecuted for this massacre until July 2004, when a trial of ten former Waffen-SS officers and NCOs living in Germany was held before a military court in La Spezia, Italy. On 22 June 2005, the court found the accused guilty of participation in the killings and sentenced them in absentia to life imprisonment:

However, extradition requests from Italy were rejected by Germany. In 2012, German prosecutors shelved their investigation of 17 unnamed former SS soldiers (eight of whom were still alive) who were part of the unit involved in the massacre because of a lack of evidence. The statement said: "Belonging to a Waffen-SS unit that was deployed to Sant'Anna di Stazzema cannot replace the need to prove individual guilt. Rather, for every defendant it must be proven that he took part in the massacre, and in which form." The mayor of the village, Michele Silicani (a survivor who was 10 when the raid occurred), called the verdict "a scandal" and said he would urge Italy's justice minister to lobby Germany to reopen the case. German deputy foreign minister Michael Georg Link commented that "while respecting the independence of the German justice system," it was not possible "to ignore that such a decision causes deep dismay and renewed suffering to Italians, not just survivors and relatives of the victims."

</snip>

List of the victims

The Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre was a Nazi German war crime committed in the hill village of Sant'Anna di Stazzema in Tuscany, Italy, in the course of an operation against the Italian resistance movement during the Italian Campaign of World War II. On 12 August 1944 the Waffen-SS, with the help of the Brigate Nere, murdered about 560 local villagers and refugees, including more than a hundred children, and burned their bodies. These crimes have been defined as voluntary and organized acts of terrorism by the Military Tribunal of La Spezia and the highest Italian court of appeal.

Massacre

On the morning of 12 August 1944, German troops of the 2nd Battalion of SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 35 of 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS, commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Anton Galler, entered the mountain village of Sant'Anna di Stazzema. With them came some fascists of the 36th Brigata Nera Benito Mussolini based in Lucca, dressed in German uniforms.

The soldiers immediately proceeded to round up villagers and refugees, locking up hundreds of them in several barns and stables, before systematically executing them. The killings were done mostly by shooting groups of people with machine guns or by herding them into basements and other enclosed spaces and tossing in hand grenades. At the 16th-century local church, the priest Fiore Menguzzo (awarded the Medal for Civil Valor posthumously in 1999) was shot at point-blank range, after which machine guns were then turned on some 100 people gathered there. In all, the victims included at least 107 children (the youngest of whom, Anna Pardini, was only 20 days old), as well as eight pregnant women (one of whom, Evelina Berretti, had her stomach cut with a bayonet and her baby pulled out and killed separately).

The restored village church and World War I memorial in 2008

After other people were killed through the village, their corpses were set on fire (at the church, the soldiers used its pews for a bonfire to dispose of the bodies). The livestock were also exterminated and the whole village was burnt down. All this took three hours. The SS men then sat down outside the burning Sant'Anna and ate lunch.

Aftermath

The National Park of Peace monument in 2007

After the war, the church was rebuilt. The Charnel House Monument and the Historical Museum of Resistance were both built nearby. Stations of the Cross illustrate scenes from the massacre along the trail from the church to the main memorial site—the National Park of Peace, founded in 2000. The massacre inspired the novel Miracle at St. Anna by James McBride, and Spike Lee's film of the same title that was based on it.

Prosecutions

Apart from the divisional commander Max Simon,[a] no one was prosecuted for this massacre until July 2004, when a trial of ten former Waffen-SS officers and NCOs living in Germany was held before a military court in La Spezia, Italy. On 22 June 2005, the court found the accused guilty of participation in the killings and sentenced them in absentia to life imprisonment:

Werner Bruss (b. 1920, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Alfred Concina (b. 1919, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Ludwig Goering (b. 1923, former SS-Rottenführer who confessed to killing twenty women),

Karl Gropler (b. 1923, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Georg Rauch (b. 1921, former SS-Untersturmführer),

Horst Richter (b. 1921, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Alfred Schoneberg (b. 1921, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Heinrich Schendel (b. 1922, former SS-Unterscharführer),

Gerhard Sommer, (b. 1921, former SS-Untersturmführer), and

Ludwig Heinrich Sonntag (b. 1924, former SS-Unterscharführer).

However, extradition requests from Italy were rejected by Germany. In 2012, German prosecutors shelved their investigation of 17 unnamed former SS soldiers (eight of whom were still alive) who were part of the unit involved in the massacre because of a lack of evidence. The statement said: "Belonging to a Waffen-SS unit that was deployed to Sant'Anna di Stazzema cannot replace the need to prove individual guilt. Rather, for every defendant it must be proven that he took part in the massacre, and in which form." The mayor of the village, Michele Silicani (a survivor who was 10 when the raid occurred), called the verdict "a scandal" and said he would urge Italy's justice minister to lobby Germany to reopen the case. German deputy foreign minister Michael Georg Link commented that "while respecting the independence of the German justice system," it was not possible "to ignore that such a decision causes deep dismay and renewed suffering to Italians, not just survivors and relatives of the victims."

</snip>

August 11, 2019

35 Years Ago Today; "We begin bombing in five minutes"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/We_begin_bombing_in_five_minutes

"We begin bombing in five minutes" is the last sentence of a controversial, off-the-record joke made by US President Ronald Reagan in 1984, during the "second Cold War".

While preparing for a scheduled radio address from his vacation home in California, President Reagan joked with those present about outlawing and bombing Russia. This joke was not broadcast live, but was recorded and later leaked to the public. After some brief military confusion, the Soviet Union denounced the president's joke, as did Reagan's then-opponent in the 1984 United States presidential election, Walter Mondale. Reagan's impromptu comments have had significant staying power, being referenced, cited, and used as literary inspiration as recently as 2017.

Speech

President Reagan speaking at a reelection campaign event (July 1984)

Live at 9:06 a.m. on August 11, 1984, US President Ronald Reagan made his weekly radio address from Rancho del Cielo, his vacation home near Santa Barbara, California. The actual address begins with the president announcing his signature on the Equal Access Act, a key plank in his reelection campaign: "My fellow Americans: I'm pleased to tell you that today I signed legislation that will allow student religious groups to begin enjoying a right they've too long been denied—the freedom to meet in public high schools during nonschool hours, just as other student groups are allowed to do."

It was prior to the speech itself, while the president was joking with the National Public Radio audio engineers during soundcheck, that he riffed on his own speech, saying:

This sort of levity was not uncommon for Reagan; he was known to inject soundchecks, outtakes, and downtime with his humor throughout his career in both show business and politics.

Leak

In the minutes before the president gave his speech, a live feed from Rancho del Cielo was still being transmitted to radio stations around the United States. Many rebroadcasters were already recording the feed, and therefore the president's pre-speech joke, to be ready for the official transmission. While many in the media heard the president's impromptu remarks as he gave them, they were not broadcast live.

In October 1982, President Reagan had made similarly impolitic remarks about the Polish People's Republic. As he prepared to announce his cancellation of Poland's most favoured nation status (in retaliation for suppression of the Polish trade union Solidarity), Reagan called the military government "a bunch of no-good, lousy bums." These recorded comments were aired by "NCB". As a result of this leak, members of the White House Correspondents' Association agreed not to publish such unprepared, off-the-record presidential remarks in the future.

Both CBS News and Cable News Network recorded the 1984 joke, but kept the president's remarks under wraps in accordance with the White House agreement. However, rumors of the joke quickly spread, and by August 13 the actual quotation had been published by outlets such as Gannett News Service. Then-White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes declined to comment on August 13, saying, "I don’t talk about off-the-record stuff."

Reactions

Soviet

By August 14, the recording of Reagan's joke had become world news. On August 15, someone who the National Security Agency described to US Representative Michael D. Barnes as "a wayward operator in the Soviet Far Eastern command" sent a coded message from Vladivostok that said, in part, "We now embark on military action against the U.S. forces." Japanese and US intelligence decoded the message and raised the alert state in that part of the world; Soviet naval vessels in the North Pacific, on the other hand, contacted Vladivostok in confusion. The US never saw any evidence of Soviet attack preparations, and the alert status as promulgated by Vladivostok was canceled within 30 minutes.

Initially, on August 13, the deputy minister of Soviet foreign affairs (Valentin Kamenev) told reporters, "I have nothing to say." By the next day, though, President Reagan's leaked comments were denounced by the Soviet government, Pravda, Izvestia, and TASS as "unprecedentedly hostile," as evidence of the United States' insincerity at trying to improve Soviet Union–United States relations, and as abuse of the office of the president. "Western diplomats" described the Soviet response as over-the-top, suggesting it was an effort to give themselves more collateral at the negotiating table with the US.[6] US officials were compelled to mollify the Soviet Union and assure the United States' Cold War adversary that "Reagan’s offhand remark did not reflect White House policies or U.S. military intentions."

Domestic

Reagan's poll numbers took a hit from the political gaffe, temporarily raising the hopes of Walter Mondale supporters in the run-up to the 1984 United States presidential election. Mondale said of Reagan's joke, "A President has to be very, very careful with his words." However, in the analysis of historian Craig Shirley and Ozy author Sean Braswell, the leak of Reagan's joke was poorly utilized by the Democratic Party; "[criticism of the joke] actually worked against the Democrats and for Reagan […] as they came across as hypersensitive, and Reagan as calm, cool and collected."

In 2010, Politico journalist Andrew Glass wrote, "Most commentators dismissed the joke as, at worst, poor taste. Nonetheless, it got geopolitical traction because it came at a time of heightened Cold War tensions between Washington and Moscow — which largely dissolved during Reagan’s second term". In 2011, the Deseret News listed Reagan's microphone gaffe as his sixth-best quote, expressing surprise that it was leaked only 87 days before the election.

</snip>

"We begin bombing in five minutes" is the last sentence of a controversial, off-the-record joke made by US President Ronald Reagan in 1984, during the "second Cold War".

While preparing for a scheduled radio address from his vacation home in California, President Reagan joked with those present about outlawing and bombing Russia. This joke was not broadcast live, but was recorded and later leaked to the public. After some brief military confusion, the Soviet Union denounced the president's joke, as did Reagan's then-opponent in the 1984 United States presidential election, Walter Mondale. Reagan's impromptu comments have had significant staying power, being referenced, cited, and used as literary inspiration as recently as 2017.

Speech

President Reagan speaking at a reelection campaign event (July 1984)

Live at 9:06 a.m. on August 11, 1984, US President Ronald Reagan made his weekly radio address from Rancho del Cielo, his vacation home near Santa Barbara, California. The actual address begins with the president announcing his signature on the Equal Access Act, a key plank in his reelection campaign: "My fellow Americans: I'm pleased to tell you that today I signed legislation that will allow student religious groups to begin enjoying a right they've too long been denied—the freedom to meet in public high schools during nonschool hours, just as other student groups are allowed to do."

It was prior to the speech itself, while the president was joking with the National Public Radio audio engineers during soundcheck, that he riffed on his own speech, saying:

My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.

This sort of levity was not uncommon for Reagan; he was known to inject soundchecks, outtakes, and downtime with his humor throughout his career in both show business and politics.

Leak

In the minutes before the president gave his speech, a live feed from Rancho del Cielo was still being transmitted to radio stations around the United States. Many rebroadcasters were already recording the feed, and therefore the president's pre-speech joke, to be ready for the official transmission. While many in the media heard the president's impromptu remarks as he gave them, they were not broadcast live.

In October 1982, President Reagan had made similarly impolitic remarks about the Polish People's Republic. As he prepared to announce his cancellation of Poland's most favoured nation status (in retaliation for suppression of the Polish trade union Solidarity), Reagan called the military government "a bunch of no-good, lousy bums." These recorded comments were aired by "NCB". As a result of this leak, members of the White House Correspondents' Association agreed not to publish such unprepared, off-the-record presidential remarks in the future.

Both CBS News and Cable News Network recorded the 1984 joke, but kept the president's remarks under wraps in accordance with the White House agreement. However, rumors of the joke quickly spread, and by August 13 the actual quotation had been published by outlets such as Gannett News Service. Then-White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes declined to comment on August 13, saying, "I don’t talk about off-the-record stuff."

Reactions

Soviet

By August 14, the recording of Reagan's joke had become world news. On August 15, someone who the National Security Agency described to US Representative Michael D. Barnes as "a wayward operator in the Soviet Far Eastern command" sent a coded message from Vladivostok that said, in part, "We now embark on military action against the U.S. forces." Japanese and US intelligence decoded the message and raised the alert state in that part of the world; Soviet naval vessels in the North Pacific, on the other hand, contacted Vladivostok in confusion. The US never saw any evidence of Soviet attack preparations, and the alert status as promulgated by Vladivostok was canceled within 30 minutes.

Initially, on August 13, the deputy minister of Soviet foreign affairs (Valentin Kamenev) told reporters, "I have nothing to say." By the next day, though, President Reagan's leaked comments were denounced by the Soviet government, Pravda, Izvestia, and TASS as "unprecedentedly hostile," as evidence of the United States' insincerity at trying to improve Soviet Union–United States relations, and as abuse of the office of the president. "Western diplomats" described the Soviet response as over-the-top, suggesting it was an effort to give themselves more collateral at the negotiating table with the US.[6] US officials were compelled to mollify the Soviet Union and assure the United States' Cold War adversary that "Reagan’s offhand remark did not reflect White House policies or U.S. military intentions."

Domestic

Reagan's poll numbers took a hit from the political gaffe, temporarily raising the hopes of Walter Mondale supporters in the run-up to the 1984 United States presidential election. Mondale said of Reagan's joke, "A President has to be very, very careful with his words." However, in the analysis of historian Craig Shirley and Ozy author Sean Braswell, the leak of Reagan's joke was poorly utilized by the Democratic Party; "[criticism of the joke] actually worked against the Democrats and for Reagan […] as they came across as hypersensitive, and Reagan as calm, cool and collected."

In 2010, Politico journalist Andrew Glass wrote, "Most commentators dismissed the joke as, at worst, poor taste. Nonetheless, it got geopolitical traction because it came at a time of heightened Cold War tensions between Washington and Moscow — which largely dissolved during Reagan’s second term". In 2011, the Deseret News listed Reagan's microphone gaffe as his sixth-best quote, expressing surprise that it was leaked only 87 days before the election.

</snip>

August 11, 2019

54 Years Ago Today; The Watts Rebellion begins

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watts_riots

Burning buildings during the riots

The Watts riots, sometimes referred to as the Watts Rebellion, took place in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles from August 11 to 16, 1965.

On August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, an African-American motorist on parole for robbery, was pulled over for reckless driving. A minor roadside argument broke out, and then escalated into a fight with police. Community members reported that the police had hurt a pregnant woman, and six days of civil unrest followed. Nearly 4,000 members of the California Army National Guard helped suppress the disturbance, which resulted in 34 deaths and over $40 million in property damage. It was the city's worst unrest until the Rodney King riots of 1992.

<snip>

Inciting incident

On the evening of Wednesday, August 11, 1965, 21-year-old Marquette Frye, an African-American man driving his mother's 1955 Buick, was pulled over by California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer Lee Minikus for alleged reckless driving . After administering a field sobriety test, Minikus placed Frye under arrest and radioed for his vehicle to be impounded. Marquette's brother, Ronald, a passenger in the vehicle, walked to their house nearby, bringing their mother, Rena Price, back with him to the scene of the arrest.

When Rena Price reached the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street that evening, she scolded Frye about drinking and driving, as he recalled in a 1985 interview with the Orlando Sentinel. But the situation quickly escalated: someone shoved Price, Frye was struck, Price jumped an officer, and another officer pulled out a shotgun. Backup police officers attempted to arrest Frye by using physical force to subdue him. After community members reported that police had roughed up Frye and kicked a pregnant woman, angry mobs formed. As the situation intensified, growing crowds of local residents watching the exchange began yelling and throwing objects at the police officers. Frye's mother and brother fought with the officers and were eventually arrested along with Marquette Frye.

After the arrests of Price and her sons the Frye brothers, the crowd continued to grow along Avalon Boulevard. Police came to the scene to break up the crowd several times that night, but were attacked when people threw rocks and chunks of concrete. A 46-square-mile (119 square kilometer) swath of Los Angeles was transformed into a combat zone during the ensuing six days.

Riot begins

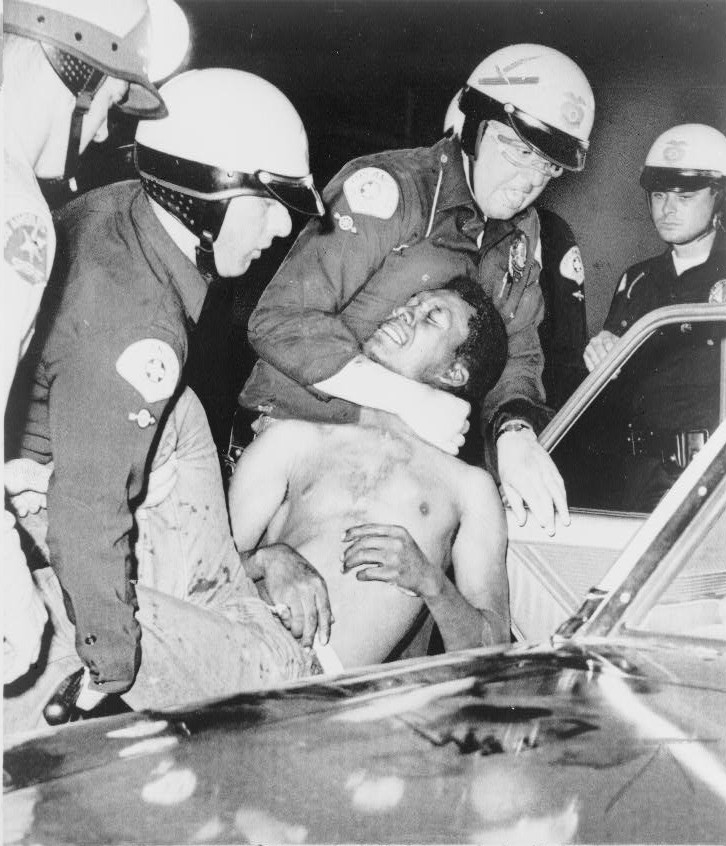

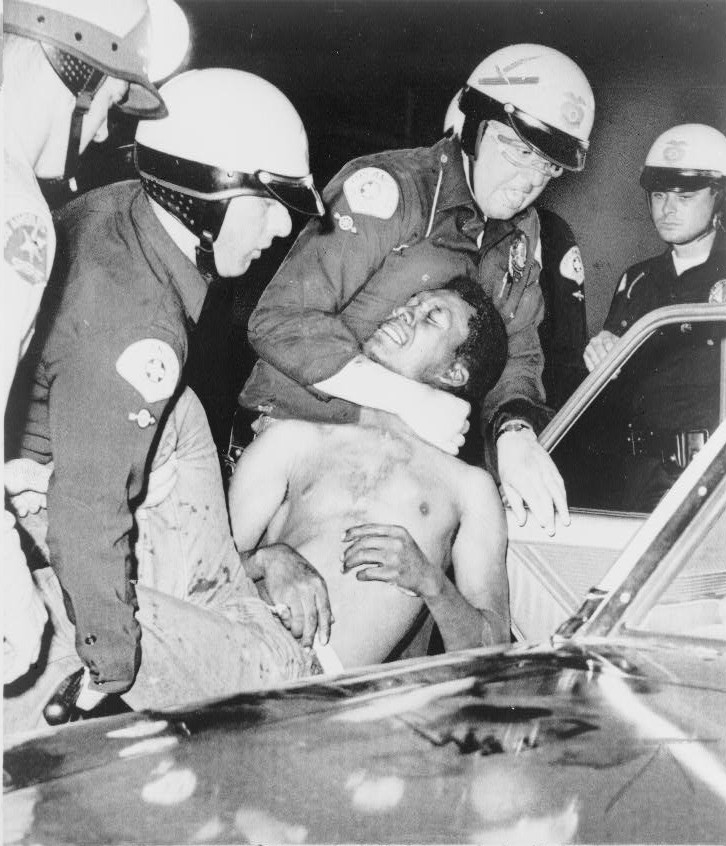

Police arrest a man during the riots on August 12

After a night of increasing unrest, police and local black community leaders held a community meeting on Thursday, August 12, to discuss an action plan and to urge calm. The meeting failed. Later that day, Los Angeles police chief William H. Parker called for the assistance of the California Army National Guard. Chief Parker believed the riots resembled an insurgency, compared it to fighting the Viet Cong, and decreed a "paramilitary" response to the disorder. Governor Pat Brown declared that law enforcement was confronting "guerrillas fighting with gangsters".

The rioting intensified, and on Friday, August 13, about 2,300 National Guardsmen joined the police in trying to maintain order on the streets. Sergeant Ben Dunn said: "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America." By nightfall on Saturday, 16,000 law enforcement personnel had been mobilized and patrolled the city. Blockades were established, and warning signs were posted throughout the riot zones threatening the use of deadly force (one sign warned residents to "Turn left or get shot" ). 23 of the 34 people killed during the riots were shot by law enforcement or National Guardsmen. Angered over the police response, residents of Watts engaged in a full-scale battle against the law enforcement personnel. Rioters tore up sidewalks and bricks to hurl at Guardsmen and police, and to smash their vehicles.

Those actively participating in the riots started physical fights with police, blocked Los Angeles Fire Department personnel from using fire hoses on protesters, or stopped and beat white motorists yelling racial slurs in the area. Arson and looting were largely confined to local white-owned stores and businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to low wages and high prices for local workers.

To quell the riots, Chief Parker initiated a policy of mass arrest. Following the deployment of National Guardsmen, a curfew was declared for a vast region of South Central Los Angeles. In addition to the Guardsmen, 934 Los Angeles police officers and 718 officers from the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department were deployed during the rioting. Watts and all black-majority areas in Los Angeles were put under the curfew. All residents outside of their homes in the affected areas after 8:00pm were subject to arrest. Eventually nearly 3,500 people were arrested, primarily for curfew violations. By the morning of Sunday, August 15, the riots had largely been quelled.

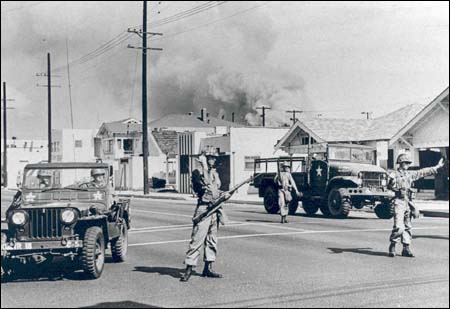

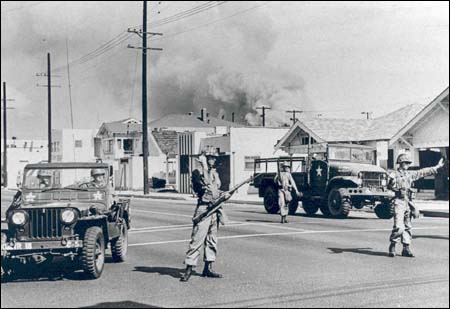

Soldiers of the California's 40th Armored Division direct traffic away from an area of South Central Los Angeles burning during the Watts riot

Over the course of six days, between 31,000 and 35,000 adults participated in the riots. Around 70,000 people were "sympathetic, but not active." Over the six days, there were 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries, 3,438 arrests, and over $40 million in property damage. Many white Americans were fearful of the breakdown of social order in Watts, especially since white motorists were being pulled over by rioters in nearby areas and assaulted. Many in the black community, however, believed the rioters were taking part in an "uprising against an oppressive system." In a 1966 essay, black civil rights activist Bayard Rustin wrote:

The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.

Despite allegations that "criminal elements" were responsible for the riots, the vast majority of those arrested had no prior criminal record.

Parker publicly said that the people he saw rioting were acting like "monkeys in the zoo." Overall, an estimated $40 million in damage was caused ($320,000,000 in 2019 dollars), with almost 1,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. Homes were not attacked, although some caught fire due to proximity to other fires.

</snip>

Burning buildings during the riots

The Watts riots, sometimes referred to as the Watts Rebellion, took place in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles from August 11 to 16, 1965.

On August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, an African-American motorist on parole for robbery, was pulled over for reckless driving. A minor roadside argument broke out, and then escalated into a fight with police. Community members reported that the police had hurt a pregnant woman, and six days of civil unrest followed. Nearly 4,000 members of the California Army National Guard helped suppress the disturbance, which resulted in 34 deaths and over $40 million in property damage. It was the city's worst unrest until the Rodney King riots of 1992.

<snip>

Inciting incident

On the evening of Wednesday, August 11, 1965, 21-year-old Marquette Frye, an African-American man driving his mother's 1955 Buick, was pulled over by California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer Lee Minikus for alleged reckless driving . After administering a field sobriety test, Minikus placed Frye under arrest and radioed for his vehicle to be impounded. Marquette's brother, Ronald, a passenger in the vehicle, walked to their house nearby, bringing their mother, Rena Price, back with him to the scene of the arrest.

When Rena Price reached the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street that evening, she scolded Frye about drinking and driving, as he recalled in a 1985 interview with the Orlando Sentinel. But the situation quickly escalated: someone shoved Price, Frye was struck, Price jumped an officer, and another officer pulled out a shotgun. Backup police officers attempted to arrest Frye by using physical force to subdue him. After community members reported that police had roughed up Frye and kicked a pregnant woman, angry mobs formed. As the situation intensified, growing crowds of local residents watching the exchange began yelling and throwing objects at the police officers. Frye's mother and brother fought with the officers and were eventually arrested along with Marquette Frye.

After the arrests of Price and her sons the Frye brothers, the crowd continued to grow along Avalon Boulevard. Police came to the scene to break up the crowd several times that night, but were attacked when people threw rocks and chunks of concrete. A 46-square-mile (119 square kilometer) swath of Los Angeles was transformed into a combat zone during the ensuing six days.

Riot begins

Police arrest a man during the riots on August 12

After a night of increasing unrest, police and local black community leaders held a community meeting on Thursday, August 12, to discuss an action plan and to urge calm. The meeting failed. Later that day, Los Angeles police chief William H. Parker called for the assistance of the California Army National Guard. Chief Parker believed the riots resembled an insurgency, compared it to fighting the Viet Cong, and decreed a "paramilitary" response to the disorder. Governor Pat Brown declared that law enforcement was confronting "guerrillas fighting with gangsters".

The rioting intensified, and on Friday, August 13, about 2,300 National Guardsmen joined the police in trying to maintain order on the streets. Sergeant Ben Dunn said: "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America." By nightfall on Saturday, 16,000 law enforcement personnel had been mobilized and patrolled the city. Blockades were established, and warning signs were posted throughout the riot zones threatening the use of deadly force (one sign warned residents to "Turn left or get shot" ). 23 of the 34 people killed during the riots were shot by law enforcement or National Guardsmen. Angered over the police response, residents of Watts engaged in a full-scale battle against the law enforcement personnel. Rioters tore up sidewalks and bricks to hurl at Guardsmen and police, and to smash their vehicles.

Those actively participating in the riots started physical fights with police, blocked Los Angeles Fire Department personnel from using fire hoses on protesters, or stopped and beat white motorists yelling racial slurs in the area. Arson and looting were largely confined to local white-owned stores and businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to low wages and high prices for local workers.

To quell the riots, Chief Parker initiated a policy of mass arrest. Following the deployment of National Guardsmen, a curfew was declared for a vast region of South Central Los Angeles. In addition to the Guardsmen, 934 Los Angeles police officers and 718 officers from the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department were deployed during the rioting. Watts and all black-majority areas in Los Angeles were put under the curfew. All residents outside of their homes in the affected areas after 8:00pm were subject to arrest. Eventually nearly 3,500 people were arrested, primarily for curfew violations. By the morning of Sunday, August 15, the riots had largely been quelled.

Soldiers of the California's 40th Armored Division direct traffic away from an area of South Central Los Angeles burning during the Watts riot

Over the course of six days, between 31,000 and 35,000 adults participated in the riots. Around 70,000 people were "sympathetic, but not active." Over the six days, there were 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries, 3,438 arrests, and over $40 million in property damage. Many white Americans were fearful of the breakdown of social order in Watts, especially since white motorists were being pulled over by rioters in nearby areas and assaulted. Many in the black community, however, believed the rioters were taking part in an "uprising against an oppressive system." In a 1966 essay, black civil rights activist Bayard Rustin wrote:

The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.

Despite allegations that "criminal elements" were responsible for the riots, the vast majority of those arrested had no prior criminal record.

Parker publicly said that the people he saw rioting were acting like "monkeys in the zoo." Overall, an estimated $40 million in damage was caused ($320,000,000 in 2019 dollars), with almost 1,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. Homes were not attacked, although some caught fire due to proximity to other fires.

</snip>

August 11, 2019

Oops! That's Hedy...

77 Years Ago Today; Hedy Lamarr & George Antheil receive patent for Frequency-hopping spread spectru

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frequency-hopping_spread_spectrum

Frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) is a method of transmitting radio signals by rapidly switching a carrier among many frequency channels, using a pseudorandom sequence known to both transmitter and receiver. It is used as a multiple access method in the code division multiple access (CDMA) scheme frequency-hopping code division multiple access (FH-CDMA).

Each available frequency band is divided into sub-frequencies. Signals rapidly change ("hop" ) among these in a predetermined order. Interference at a specific frequency will only affect the signal during that short interval. FHSS can, however, cause interference with adjacent direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) systems.

Adaptive frequency-hopping spread spectrum (AFH), a specific type of FHSS, is used in Bluetooth wireless data transfer.

<snip>

Multiple inventors

In 1899 Guglielmo Marconi experimented with frequency-selective reception in an attempt to minimise interference.

The earliest mentions of frequency hopping in the open literature are in US patent 725,605 awarded to Nikola Tesla in March 17, 1903 and in radio pioneer Jonathan Zenneck's book Wireless Telegraphy (German, 1908, English translation McGraw Hill, 1915), although Zenneck himself states that Telefunken had already tried it. Nikola Tesla doesn’t mention the phrase “frequency hopping” directly, but certainly alludes to it. Entitled Method of Signaling, the patent describes a system that would enable radio communication without any danger of the signals or messages being disturbed, intercepted, interfered with in any way .

The German military made limited use of frequency hopping for communication between fixed command points in World War I to prevent eavesdropping by British forces, who did not have the technology to follow the sequence.

A Polish engineer and inventor, Leonard Danilewicz, came up with the idea in 1929. Several other patents were taken out in the 1930s, including one by Willem Broertjes (U.S. Patent 1,869,659, issued Aug. 2, 1932).

During World War II, the US Army Signal Corps was inventing a communication system called SIGSALY, which incorporated spread spectrum in a single frequency context. However, SIGSALY was a top-secret communications system, so its existence did not become known until the 1980s.

A patent was awarded to actress Hedy Lamarr and composer George Antheil, who in 1942 received U.S. Patent 2,292,387 for their "Secret Communications System". This intended early version of frequency hopping was supposed to use a piano-roll to change among 88 frequencies, and was intended to make radio-guided torpedoes harder for enemies to detect or to jam, but there is no record of a working device ever being produced. The patent was rediscovered in the 1950s during patent searches when private companies independently developed Code Division Multiple Access, a non-frequency-hopping form of spread-spectrum, and has been cited numerous times since.

A practical application of frequency hopping was developed by Ray Zinn, co-founder of Micrel Corporation. Zinn developed a method allowing radio devices to operate without the need to synchronize a receiver with a transmitter. Using frequency hopping and sweep modes, Zinn's method is primarily applied in low data rate wireless applications such as utility metering, machine and equipment monitoring and metering, and remote control. In 2006 Zinn received U.S. Patent 6,996,399 for his "Wireless device and method using frequency hopping and sweep modes."

</snip>

Frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) is a method of transmitting radio signals by rapidly switching a carrier among many frequency channels, using a pseudorandom sequence known to both transmitter and receiver. It is used as a multiple access method in the code division multiple access (CDMA) scheme frequency-hopping code division multiple access (FH-CDMA).

Each available frequency band is divided into sub-frequencies. Signals rapidly change ("hop" ) among these in a predetermined order. Interference at a specific frequency will only affect the signal during that short interval. FHSS can, however, cause interference with adjacent direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) systems.

Adaptive frequency-hopping spread spectrum (AFH), a specific type of FHSS, is used in Bluetooth wireless data transfer.

<snip>

Multiple inventors

In 1899 Guglielmo Marconi experimented with frequency-selective reception in an attempt to minimise interference.

The earliest mentions of frequency hopping in the open literature are in US patent 725,605 awarded to Nikola Tesla in March 17, 1903 and in radio pioneer Jonathan Zenneck's book Wireless Telegraphy (German, 1908, English translation McGraw Hill, 1915), although Zenneck himself states that Telefunken had already tried it. Nikola Tesla doesn’t mention the phrase “frequency hopping” directly, but certainly alludes to it. Entitled Method of Signaling, the patent describes a system that would enable radio communication without any danger of the signals or messages being disturbed, intercepted, interfered with in any way .

The German military made limited use of frequency hopping for communication between fixed command points in World War I to prevent eavesdropping by British forces, who did not have the technology to follow the sequence.

A Polish engineer and inventor, Leonard Danilewicz, came up with the idea in 1929. Several other patents were taken out in the 1930s, including one by Willem Broertjes (U.S. Patent 1,869,659, issued Aug. 2, 1932).

During World War II, the US Army Signal Corps was inventing a communication system called SIGSALY, which incorporated spread spectrum in a single frequency context. However, SIGSALY was a top-secret communications system, so its existence did not become known until the 1980s.

A patent was awarded to actress Hedy Lamarr and composer George Antheil, who in 1942 received U.S. Patent 2,292,387 for their "Secret Communications System". This intended early version of frequency hopping was supposed to use a piano-roll to change among 88 frequencies, and was intended to make radio-guided torpedoes harder for enemies to detect or to jam, but there is no record of a working device ever being produced. The patent was rediscovered in the 1950s during patent searches when private companies independently developed Code Division Multiple Access, a non-frequency-hopping form of spread-spectrum, and has been cited numerous times since.

A practical application of frequency hopping was developed by Ray Zinn, co-founder of Micrel Corporation. Zinn developed a method allowing radio devices to operate without the need to synchronize a receiver with a transmitter. Using frequency hopping and sweep modes, Zinn's method is primarily applied in low data rate wireless applications such as utility metering, machine and equipment monitoring and metering, and remote control. In 2006 Zinn received U.S. Patent 6,996,399 for his "Wireless device and method using frequency hopping and sweep modes."

</snip>

Oops! That's Hedy...

August 9, 2019

50 Years Ago Today; The Tate Murders (Warning: GRAPHIC descriptions)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tate_murders

Sharon Tate in a still from a trailer for the 1966 film Eye of the Devil; she was murdered by the Manson Family.

The Tate murders were a mass murder, conducted by members of the Manson Family on August 8–9, 1969, of five adults, including Sharon Tate who was pregnant at the time. Four members of the Manson Family invaded the rented home of a married celebrity couple, actress Sharon Tate and director Roman Polanski at 10050 Cielo Drive in Los Angeles. They murdered Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant, along with three friends who were visiting at the time, and an 18-year-old visitor, who was slain as he was departing the home. Polanski was not present on the night of the murders, as he was working on a film in Europe.

The murders were carried out by Tex Watson, Susan Atkins, and Patricia Krenwinkel, under the direction of Charles Manson. Watson drove Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian from Spahn Ranch to the residence on Cielo Drive. Manson, a would-be musician, had previously attempted to enter into a recording contract with record producer Terry Melcher, who was a previous renter (from May 1966 to January 1969) of the house along with musician Mark Lindsay and Melcher's then-girlfriend, actress Candice Bergen. Melcher had snubbed Manson, leaving him disgruntled.

Murders

On the night of August 8, 1969, Tex Watson took Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian, and Patricia Krenwinkel to "that house where Melcher used to live," as Manson had instructed him, to "totally destroy everyone in [it], as gruesome as you can". Manson had told the women to do as Watson would instruct them. Krenwinkel was one of the early Family members and had allegedly been picked up by Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys while hitchhiking.

The occupants of the house at 10050 Cielo Drive that evening, all of whom were strangers to the Manson followers, were movie actress and fashion model Sharon Tate, who was eight-and-a half months pregnant and the wife of film director Roman Polanski; her friend and former lover Jay Sebring, a noted hairstylist; Polanski's friend and aspiring screenwriter Wojciech Frykowski; and Frykowski's lover Abigail Folger, heiress to the Folger coffee fortune, and daughter of Peter Folger. Polanski was in Europe working on a film project; Tate had accompanied him, but returned home three weeks earlier. Music producer Quincy Jones, a friend of Sebring, had planned to join him that evening, but did not go.

When the group arrived at the entrance to the property, Watson, who had been to the house on at least one other occasion, climbed a telephone pole near the entrance gate and cut the phone line to the house.

The group backed their car to the bottom of the hill that led to the estate, parked, and walked back up to the house. Thinking the gate might be electrified or equipped with an alarm, they climbed a brushy embankment to the right of the gate and entered the grounds.

Just then, headlights approached them from farther within the angled property. Watson ordered the women to lie in the bushes. He stepped out and ordered the approaching driver to halt. Eighteen-year-old student Steven Parent had been visiting the property's caretaker, William Garretson, who lived in the property's guest house. As Watson leveled a .22-caliber revolver at Parent, the frightened youth begged Watson not to hurt him, claiming that he would not say anything. Watson lunged at Parent with a knife, giving him a defensive slash wound on the palm of his hand (severing tendons and tearing the boy's watch off his wrist), then shot him four times in the chest and abdomen, killing him. Watson ordered the women to help push the car further up the driveway.

After traversing the front lawn and having Kasabian search for an open window to the main house, Watson cut the screen of a window. Watson told Kasabian to keep watch down by the gate; she walked over to Parent's AMC Ambassador and waited. Watson removed the screen, entered through the window, and let Atkins and Krenwinkel in through the front door.

As Watson whispered to Atkins, a sleeping Frykowski awoke on the living room couch; Watson kicked him in the head. When Frykowski asked him who he was and what he was doing there, Watson replied: "I'm the devil, and I'm here to do the devil's business."

On Watson's direction, Atkins found the house's three other occupants and, with Krenwinkel's help, forced them to the living room. Watson began to tie Tate and Sebring together by their necks with rope he had brought and slung up over one of the living room's ceiling beams. Sebring's protest – his second – of rough treatment of the pregnant Tate prompted Watson to shoot him. Folger was taken momentarily back to her bedroom for her purse, out of which she gave the intruders $70. After that, Watson stabbed the groaning Sebring seven times.

Frykowski's hands had been bound with a towel. Freeing himself, Frykowski began struggling with Atkins, who stabbed at his legs with the knife with which she had been guarding him. As he fought his way toward and out the front door, onto the porch, Watson caught up with Frykowski and struck him over the head with the gun multiple times, stabbed him repeatedly, and shot him twice.

Around this time, Kasabian was drawn up from the driveway by "horrifying sounds". She arrived outside the door. In a vain effort to halt the massacre, she falsely told Atkins that someone was coming.

Inside the house, Folger had escaped from Krenwinkel and fled out a bedroom door to the pool area. Folger was pursued to the front lawn by Krenwinkel, who caught her, stabbed her, and finally tackled her to the ground. She was killed by Watson, who stabbed her 28 times. As Frykowski struggled across the lawn, Watson murdered him with a final flurry of stabbings. Frykowski was stabbed a total of 51 times.

In the house, Tate pleaded to be allowed to live long enough to give birth, and offered herself as a hostage in an attempt to save the life of her fetus. At this point either Atkins, Watson, or both killed Tate, who was stabbed 16 times. Watson later wrote that as she was being killed, Tate cried: "Mother ... mother ..."

Earlier, as the four Family members had been heading out from Spahn Ranch, Manson had told the women to "leave a sign ... something witchy". Using the towel that had bound Frykowski's hands, Atkins wrote "pig" on the house's front door in Tate's blood. En route home, the killers changed out of their bloody clothes, which they disposed of in the hills along with their weapons.

</snip>

Sharon Tate in a still from a trailer for the 1966 film Eye of the Devil; she was murdered by the Manson Family.

The Tate murders were a mass murder, conducted by members of the Manson Family on August 8–9, 1969, of five adults, including Sharon Tate who was pregnant at the time. Four members of the Manson Family invaded the rented home of a married celebrity couple, actress Sharon Tate and director Roman Polanski at 10050 Cielo Drive in Los Angeles. They murdered Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant, along with three friends who were visiting at the time, and an 18-year-old visitor, who was slain as he was departing the home. Polanski was not present on the night of the murders, as he was working on a film in Europe.

The murders were carried out by Tex Watson, Susan Atkins, and Patricia Krenwinkel, under the direction of Charles Manson. Watson drove Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian from Spahn Ranch to the residence on Cielo Drive. Manson, a would-be musician, had previously attempted to enter into a recording contract with record producer Terry Melcher, who was a previous renter (from May 1966 to January 1969) of the house along with musician Mark Lindsay and Melcher's then-girlfriend, actress Candice Bergen. Melcher had snubbed Manson, leaving him disgruntled.

Murders

On the night of August 8, 1969, Tex Watson took Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian, and Patricia Krenwinkel to "that house where Melcher used to live," as Manson had instructed him, to "totally destroy everyone in [it], as gruesome as you can". Manson had told the women to do as Watson would instruct them. Krenwinkel was one of the early Family members and had allegedly been picked up by Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys while hitchhiking.

The occupants of the house at 10050 Cielo Drive that evening, all of whom were strangers to the Manson followers, were movie actress and fashion model Sharon Tate, who was eight-and-a half months pregnant and the wife of film director Roman Polanski; her friend and former lover Jay Sebring, a noted hairstylist; Polanski's friend and aspiring screenwriter Wojciech Frykowski; and Frykowski's lover Abigail Folger, heiress to the Folger coffee fortune, and daughter of Peter Folger. Polanski was in Europe working on a film project; Tate had accompanied him, but returned home three weeks earlier. Music producer Quincy Jones, a friend of Sebring, had planned to join him that evening, but did not go.

When the group arrived at the entrance to the property, Watson, who had been to the house on at least one other occasion, climbed a telephone pole near the entrance gate and cut the phone line to the house.

The group backed their car to the bottom of the hill that led to the estate, parked, and walked back up to the house. Thinking the gate might be electrified or equipped with an alarm, they climbed a brushy embankment to the right of the gate and entered the grounds.

Just then, headlights approached them from farther within the angled property. Watson ordered the women to lie in the bushes. He stepped out and ordered the approaching driver to halt. Eighteen-year-old student Steven Parent had been visiting the property's caretaker, William Garretson, who lived in the property's guest house. As Watson leveled a .22-caliber revolver at Parent, the frightened youth begged Watson not to hurt him, claiming that he would not say anything. Watson lunged at Parent with a knife, giving him a defensive slash wound on the palm of his hand (severing tendons and tearing the boy's watch off his wrist), then shot him four times in the chest and abdomen, killing him. Watson ordered the women to help push the car further up the driveway.

After traversing the front lawn and having Kasabian search for an open window to the main house, Watson cut the screen of a window. Watson told Kasabian to keep watch down by the gate; she walked over to Parent's AMC Ambassador and waited. Watson removed the screen, entered through the window, and let Atkins and Krenwinkel in through the front door.

As Watson whispered to Atkins, a sleeping Frykowski awoke on the living room couch; Watson kicked him in the head. When Frykowski asked him who he was and what he was doing there, Watson replied: "I'm the devil, and I'm here to do the devil's business."

On Watson's direction, Atkins found the house's three other occupants and, with Krenwinkel's help, forced them to the living room. Watson began to tie Tate and Sebring together by their necks with rope he had brought and slung up over one of the living room's ceiling beams. Sebring's protest – his second – of rough treatment of the pregnant Tate prompted Watson to shoot him. Folger was taken momentarily back to her bedroom for her purse, out of which she gave the intruders $70. After that, Watson stabbed the groaning Sebring seven times.

Frykowski's hands had been bound with a towel. Freeing himself, Frykowski began struggling with Atkins, who stabbed at his legs with the knife with which she had been guarding him. As he fought his way toward and out the front door, onto the porch, Watson caught up with Frykowski and struck him over the head with the gun multiple times, stabbed him repeatedly, and shot him twice.

Around this time, Kasabian was drawn up from the driveway by "horrifying sounds". She arrived outside the door. In a vain effort to halt the massacre, she falsely told Atkins that someone was coming.

Inside the house, Folger had escaped from Krenwinkel and fled out a bedroom door to the pool area. Folger was pursued to the front lawn by Krenwinkel, who caught her, stabbed her, and finally tackled her to the ground. She was killed by Watson, who stabbed her 28 times. As Frykowski struggled across the lawn, Watson murdered him with a final flurry of stabbings. Frykowski was stabbed a total of 51 times.

In the house, Tate pleaded to be allowed to live long enough to give birth, and offered herself as a hostage in an attempt to save the life of her fetus. At this point either Atkins, Watson, or both killed Tate, who was stabbed 16 times. Watson later wrote that as she was being killed, Tate cried: "Mother ... mother ..."

Earlier, as the four Family members had been heading out from Spahn Ranch, Manson had told the women to "leave a sign ... something witchy". Using the towel that had bound Frykowski's hands, Atkins wrote "pig" on the house's front door in Tate's blood. En route home, the killers changed out of their bloody clothes, which they disposed of in the hills along with their weapons.

</snip>

August 7, 2019

30 Years Ago Today; Congressman Mickey Leland (D-TX) dies in plane crash in Ethiopia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mickey_Leland

George Thomas "Mickey" Leland (November 27, 1944 – August 7, 1989) was an anti-poverty activist who later became a congressman from the Texas 18th District and chair of the Congressional Black Caucus. He was a Democrat.

Early years

Leland was born in Lubbock, Texas to Alice and George Thomas Leland, II. At a very early age, the Lelands moved to Houston's Fifth Ward neighborhood.

Growing up in a predominantly African American and Hispanic neighborhood, Leland attended Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas, where he ranked in the top ten percent of his class when he graduated from Wheatley in 1964. While attending Texas Southern University in the late 1960s, he emerged as a vocal leader of the Houston-area civil rights movement and had brought national leaders of the movement to Houston. Leland graduated from Texas Southern in 1970 with a Bachelor's degree in Pharmacy. He served as an Instructor of Clinical Pharmacy at his alma mater in 1970–71, where he set up "door-to-door" outreach campaigns in low-income neighborhoods to inform people about their medical care options and performing preliminary screenings.

It was during the administration of then-Texas Southern University President Leonard O. Spearman, where Leland received an honorary doctorate degree from his alma mater.

Service in the Texas House of Representatives

In 1972, Texas for the first time allowed its State House of Representatives and Senate seats to be elected as single-member districts. Soon after the decision, five minority candidates (dubbed the "People's Five" ), including eventual winners Leland, Craig Washington and Benny Reyes ran for district seats in the Texas House of Representatives, a first for a state that, although Barbara Jordan had been a state senator, had not seen any African-American state representatives since Reconstruction.

Re-elected in 1974 and again in 1976, Leland served three two-year terms in the Texas House of Representatives, representing the 88th District and while in Austin, he became famous for being a staunch advocate of healthcare rights for poor Texans. He was responsible for the passage of legislation that provided low-income consumers with access to affordable generic drugs, and supported the creation of healthcare access through Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO's). In order to accomplish his goals in Austin, Leland served on the Texas State Labor Committee, State Affairs Committee, Human Resources Committee, Legislative Council, and the Subcommittee on Occupational and Industrial Safety. He was elected the Vice-Chairman of the Joint Committee on Prison Reform including becoming the first African American to serve on the Senate–House Conference Committee as a member of the House Appropriations Committee.

U.S. Congressman from Texas's 18th District

After six years in the Texas State Legislature, Leland was elected to the United States House of Representatives in November 1978 to represent Texas's 18th District and was re-elected easily in 1980, 1982, 1984, 1986 and again in 1988 to six two-year terms, serving until his death. The congressional district included the neighborhood where he had grown up, and he was recognized as a knowledgeable advocate for health, children and the elderly. His leadership abilities were immediately noticed in Washington, and he was named to serve as Freshman Majority Whip in his first term, and later served twice as At-Large Majority Whip. Leland was re-elected to each succeeding Congress until his death.

Mickey Leland International Terminal D at Houston's George Bush Intercontinental Airport is named after Leland.

Leland was an effective advocate on hunger and public health issues. In 1984 Leland established the congressional select committee on Hunger and initiated a number of programs designed to assuage the famine crises that plagued Ethiopia and Sudan through much of the 1980s. Leland pioneered many afro-centric cultural norms in Washington which included wearing a dashiki and African style hats.

As he visited soup kitchens and makeshift shelters, he became increasingly concerned about the hungry and homeless. The work for which he is best remembered began when Leland co-authored legislation with U.S. Rep. Ben Gilman (R-New York State) in establishing the House Select Committee on Hunger. U.S. Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill (D-Massachusetts) named Leland chairman when it was enacted in 1984. The Select Committee's mandate was to "conduct a continuing, comprehensive study and review of the problems of hunger and malnutrition."

Although the committee had no legislative jurisdiction, the committee, for the first time, provided a single focus for hunger-related issues. The committee's impact and influence would stem largely from Congressman Leland's ability to generate awareness of complex hunger alleviation issues and exert his personal moral leadership. In addition to focusing attention on issues of hunger, his legislative initiatives would create the National Commission on Infant Mortality, better access for fresh food for at-risk women, children and infants, and the first comprehensive services for the homeless.

Leland's sensitivity to the immediate needs of poor and hungry people would soon make him a spokesperson for hungry people on a far broader scale. Reports of acute famine in sub-Saharan Africa immediately prompted Speaker O'Neill to ask Leland to lead a bipartisan Congressional delegation to assess conditions and relief requirements. When Leland returned, he brought together entertainment personalities, religious leaders and private voluntary agencies to create general public support for the Africa Famine Relief and Recovery Act of 1985. That legislation provided $800 million in food and humanitarian relief supplies. The international attention Leland had focused on the famine brought additional support for non-governmental efforts, saving thousands of lives.

His ability in reaching out to others with innovative ideas and to gain support from unlikely sources was a key to his success in effectively addressing the problems for the poor and minorities. He met with both Pope John Paul II about food aid to Africa and Cuban President Fidel Castro about reuniting Cuban families. In Moscow as part of the first Congressional delegation led by a Speaker of the House as part of the post-Cold War Era, he proposed a joint US-Soviet food initiative to Mozambique. As Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Leland proudly presented the first awards the Caucus had ever given a non-black, rock musician Bob Geldorf and news anchor Ted Koppel. Geldorf honored for his Band Aid concert and fund-raising efforts for African famine victims and Koppel for his news stories on the African famine.

Leland was a powerful advocate on other major issues as well. While chairing the House Select Committee on Hunger, Leland was a member of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, and the Subcommittees on Telecommunications and Finance, Health and the Environment, and Energy and Power. He chaired the Subcommittee on Postal Operations and Services and served on the Committee on Post Office and Civil Service and the Subcommittee on Compensation and Employment.

Minority affairs

Leland was a very effective promoter of responsible and realistic broadcast television and cable programming. Through widely publicized congressional hearings he aroused the nation's conscience and reduced violence in children's television programming. He also advocated ethnic diversity through Affirmative Action in broadcast employment, both on and off camera, and ownership. In particular, he worked to assure that all of the characters in the media avoided ethnic stereotypes and fairly portrayed the rich diversity that makes up the American public. When the federal government began to privatize federal assets such as Conrail, Leland successfully included legislative language that required the participation of minority investment bankers in the negotiations. During 1985–86, Congressman Leland served as Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) during the 99th Congress. The CBC was created in 1971 with only 13 members. By 1987, the CBC had grown to 23 members. Leland was also a member of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in 1976–85. He served Chairman of the DNC's Black Caucus in 1981–85, and in that capacity, he served on the DNC's Executive Committee.

Death

On August 7, 1989, Leland died in a plane crash in Gambela, Ethiopia during a mission to Fugnido, Ethiopia.[3] A total of fifteen people died in the crash. Leland‘s friend and former fellow Texas legislator, Craig Washington, ran for and was elected to his unexpired congressional term in December 1989.

</snip>

George Thomas "Mickey" Leland (November 27, 1944 – August 7, 1989) was an anti-poverty activist who later became a congressman from the Texas 18th District and chair of the Congressional Black Caucus. He was a Democrat.

Early years

Leland was born in Lubbock, Texas to Alice and George Thomas Leland, II. At a very early age, the Lelands moved to Houston's Fifth Ward neighborhood.

Growing up in a predominantly African American and Hispanic neighborhood, Leland attended Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas, where he ranked in the top ten percent of his class when he graduated from Wheatley in 1964. While attending Texas Southern University in the late 1960s, he emerged as a vocal leader of the Houston-area civil rights movement and had brought national leaders of the movement to Houston. Leland graduated from Texas Southern in 1970 with a Bachelor's degree in Pharmacy. He served as an Instructor of Clinical Pharmacy at his alma mater in 1970–71, where he set up "door-to-door" outreach campaigns in low-income neighborhoods to inform people about their medical care options and performing preliminary screenings.

It was during the administration of then-Texas Southern University President Leonard O. Spearman, where Leland received an honorary doctorate degree from his alma mater.

Service in the Texas House of Representatives

In 1972, Texas for the first time allowed its State House of Representatives and Senate seats to be elected as single-member districts. Soon after the decision, five minority candidates (dubbed the "People's Five" ), including eventual winners Leland, Craig Washington and Benny Reyes ran for district seats in the Texas House of Representatives, a first for a state that, although Barbara Jordan had been a state senator, had not seen any African-American state representatives since Reconstruction.

Re-elected in 1974 and again in 1976, Leland served three two-year terms in the Texas House of Representatives, representing the 88th District and while in Austin, he became famous for being a staunch advocate of healthcare rights for poor Texans. He was responsible for the passage of legislation that provided low-income consumers with access to affordable generic drugs, and supported the creation of healthcare access through Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO's). In order to accomplish his goals in Austin, Leland served on the Texas State Labor Committee, State Affairs Committee, Human Resources Committee, Legislative Council, and the Subcommittee on Occupational and Industrial Safety. He was elected the Vice-Chairman of the Joint Committee on Prison Reform including becoming the first African American to serve on the Senate–House Conference Committee as a member of the House Appropriations Committee.

U.S. Congressman from Texas's 18th District

After six years in the Texas State Legislature, Leland was elected to the United States House of Representatives in November 1978 to represent Texas's 18th District and was re-elected easily in 1980, 1982, 1984, 1986 and again in 1988 to six two-year terms, serving until his death. The congressional district included the neighborhood where he had grown up, and he was recognized as a knowledgeable advocate for health, children and the elderly. His leadership abilities were immediately noticed in Washington, and he was named to serve as Freshman Majority Whip in his first term, and later served twice as At-Large Majority Whip. Leland was re-elected to each succeeding Congress until his death.

Mickey Leland International Terminal D at Houston's George Bush Intercontinental Airport is named after Leland.

Leland was an effective advocate on hunger and public health issues. In 1984 Leland established the congressional select committee on Hunger and initiated a number of programs designed to assuage the famine crises that plagued Ethiopia and Sudan through much of the 1980s. Leland pioneered many afro-centric cultural norms in Washington which included wearing a dashiki and African style hats.

As he visited soup kitchens and makeshift shelters, he became increasingly concerned about the hungry and homeless. The work for which he is best remembered began when Leland co-authored legislation with U.S. Rep. Ben Gilman (R-New York State) in establishing the House Select Committee on Hunger. U.S. Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill (D-Massachusetts) named Leland chairman when it was enacted in 1984. The Select Committee's mandate was to "conduct a continuing, comprehensive study and review of the problems of hunger and malnutrition."

Although the committee had no legislative jurisdiction, the committee, for the first time, provided a single focus for hunger-related issues. The committee's impact and influence would stem largely from Congressman Leland's ability to generate awareness of complex hunger alleviation issues and exert his personal moral leadership. In addition to focusing attention on issues of hunger, his legislative initiatives would create the National Commission on Infant Mortality, better access for fresh food for at-risk women, children and infants, and the first comprehensive services for the homeless.

Leland's sensitivity to the immediate needs of poor and hungry people would soon make him a spokesperson for hungry people on a far broader scale. Reports of acute famine in sub-Saharan Africa immediately prompted Speaker O'Neill to ask Leland to lead a bipartisan Congressional delegation to assess conditions and relief requirements. When Leland returned, he brought together entertainment personalities, religious leaders and private voluntary agencies to create general public support for the Africa Famine Relief and Recovery Act of 1985. That legislation provided $800 million in food and humanitarian relief supplies. The international attention Leland had focused on the famine brought additional support for non-governmental efforts, saving thousands of lives.

His ability in reaching out to others with innovative ideas and to gain support from unlikely sources was a key to his success in effectively addressing the problems for the poor and minorities. He met with both Pope John Paul II about food aid to Africa and Cuban President Fidel Castro about reuniting Cuban families. In Moscow as part of the first Congressional delegation led by a Speaker of the House as part of the post-Cold War Era, he proposed a joint US-Soviet food initiative to Mozambique. As Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Leland proudly presented the first awards the Caucus had ever given a non-black, rock musician Bob Geldorf and news anchor Ted Koppel. Geldorf honored for his Band Aid concert and fund-raising efforts for African famine victims and Koppel for his news stories on the African famine.

Leland was a powerful advocate on other major issues as well. While chairing the House Select Committee on Hunger, Leland was a member of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, and the Subcommittees on Telecommunications and Finance, Health and the Environment, and Energy and Power. He chaired the Subcommittee on Postal Operations and Services and served on the Committee on Post Office and Civil Service and the Subcommittee on Compensation and Employment.

Minority affairs

Leland was a very effective promoter of responsible and realistic broadcast television and cable programming. Through widely publicized congressional hearings he aroused the nation's conscience and reduced violence in children's television programming. He also advocated ethnic diversity through Affirmative Action in broadcast employment, both on and off camera, and ownership. In particular, he worked to assure that all of the characters in the media avoided ethnic stereotypes and fairly portrayed the rich diversity that makes up the American public. When the federal government began to privatize federal assets such as Conrail, Leland successfully included legislative language that required the participation of minority investment bankers in the negotiations. During 1985–86, Congressman Leland served as Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) during the 99th Congress. The CBC was created in 1971 with only 13 members. By 1987, the CBC had grown to 23 members. Leland was also a member of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in 1976–85. He served Chairman of the DNC's Black Caucus in 1981–85, and in that capacity, he served on the DNC's Executive Committee.

Death

On August 7, 1989, Leland died in a plane crash in Gambela, Ethiopia during a mission to Fugnido, Ethiopia.[3] A total of fifteen people died in the crash. Leland‘s friend and former fellow Texas legislator, Craig Washington, ran for and was elected to his unexpired congressional term in December 1989.

</snip>

August 7, 2019

45 Years Ago Today; Philippe Petit performs a high wire act between twin towers of the WTC in NYC

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippe_Petit

Philippe Petit (French pronunciation: [filip pəti]; born 13 August 1949) is a French high-wire artist who gained fame for his high-wire walk between the towers of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, 1971 as well as his high-wire walk between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, on the morning of 7 August 1974. For his unauthorized feat 400 metres (1,312 feet) above the ground – which he referred to as "le coup" – he rigged a 200-kilogram (440-pound) cable and used a custom-made 8-metre (30-foot) long, 25-kilogram (55-pound) balancing pole. He performed for 45 minutes, making eight passes along the wire. The following week, he celebrated his 25th birthday. All charges were dismissed in exchange for him doing a performance in Central Park for children.

Since then, Petit has lived in New York, where he has been artist-in-residence at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, also a location of other aerial performances. He has done wire walking as part of official celebrations in New York, across the United States, and in France and other countries, as well as teaching workshops on the art. In 2008, Man on Wire, a documentary directed by James Marsh about Petit's walk between the towers, won numerous awards. He was also the subject of a children's book and an animated adaptation of it, released in 2005. The Walk, a movie based on Petit's walk, was released in September 2015, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit and directed by Robert Zemeckis.

He also became adept at equestrianism, juggling, fencing, carpentry, rock-climbing, and bullfighting. Spurning circuses and their formulaic performances, he created his street persona on the sidewalks of Paris. In the early 1970s, he visited New York City, where he frequently juggled and worked on a slackline in Washington Square Park.

<snip>

World Trade Center walk

Petit became known to New Yorkers in the early 1970s for his frequent tightrope-walking performances and magic shows in the city parks, especially Washington Square Park. Petit's most famous performance was in August 1974, conducted on a wire between the roofs of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in Manhattan, a quarter mile above the ground. The towers were still under construction and had not yet been fully occupied. He performed for 45 minutes, making eight passes along the wire, during which he walked, danced, lay down on the wire, and saluted watchers from a kneeling position. Office workers, construction crews and policemen cheered him on.

Planning

Petit conceived his "coup" when he was 18, when he first read about the proposed construction of the Twin Towers and saw drawings of the project in a magazine, which he read in 1968 while sitting at a dentist's office. Petit was seized by the idea of performing there, and began collecting articles on the Towers whenever he could.

What was called the "artistic crime of the century" took Petit six years of planning. During this period, he learned everything he could about the buildings and their construction. In the same period, he began to perform high-wire walking at other famous places. Rigging his wire secretly, he performed as a combination of circus act and public display. In 1971, he performed his first such walk between the towers of the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, while priests were being ordained inside the building. In 1973, he walked a wire rigged between the two north pylons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, in Sydney, Australia.

In planning for the Twin Towers walk, Petit had to learn how to accommodate such issues as the swaying of the high towers due to wind, which was part of their design; effects of wind and weather on the wire at that height, how to rig a 200 ft (61 m) steel cable across the 138 ft (42 m) gap between the towers (at a height of 1,368 ft (417 m)), and how to gain entry with his collaborators, first to scope out the conditions and lastly, to stage the project. They had to get heavy equipment to the rooftops. He traveled to New York on numerous occasions to make first-hand observations.

Since the towers were still under construction, Petit and one of his collaborators, New York-based photographer Jim Moore, rented a helicopter to take aerial photographs of the buildings. Jean-François and Jean-Louis helped him practice in a field in France, and accompanied him to take part in the final rigging of the project, as well as to photograph it. Francis Brunn, a German juggler, provided financial support for the proposed project and its planning.

Petit and his crew gained entry into the towers several times and hid in upper floors and on the roofs of the unfinished buildings in order to study security measures. They also analyzed the construction and identified places to anchor the wire and cavalletti[dubious – discuss]. Using his own observations, drawings, and Moore's photographs, Petit constructed a scale model of the towers in order to design the needed rigging for the wire walk.

Working from an ID of an American who worked in the building, Petit made fake identification cards for himself and his collaborators (claiming that they were contractors who were installing an electrified fence on the roof) to gain access to the buildings. Prior to this, Petit had carefully observed the clothes worn by construction workers and the kinds of tools they carried. He also took note of the clothing of office workers so that some of his collaborators could pose as white collar workers. He observed what time the workers arrived and left, so he could determine when he would have roof access.