marble falls

marble falls's JournalBlack History: day 16 - 8 Black Panther Party Programs More Empowering Than Federal Programs

8 Black Panther Party Programs That Were More Empowering Than Federal Government Programs

By

Nick Chiles -

March 26, 2015

https://atlantablackstar.com/2015/03/26/8-black-panther-party-programs-that-were-more-empowering-than-federal-government-programs/4/

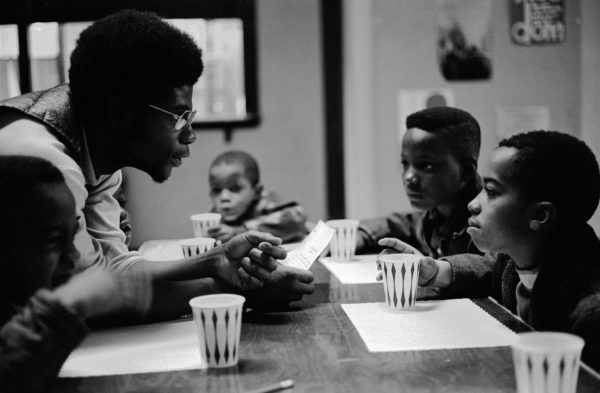

The Breakfast Program

The free breakfast for schoolchildren program was set up in Berkeley, California, in 1968 by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton. It was the first significant community program organized by the Panthers, and perhaps the most well known. By the end of 1969, free breakfast was served in 19 cities, under the sponsorship of the national headquarters and 23 local affiliates. More than 20,000 children received full free breakfast (bread, bacon, eggs, grits) before going to their elementary or junior high school.

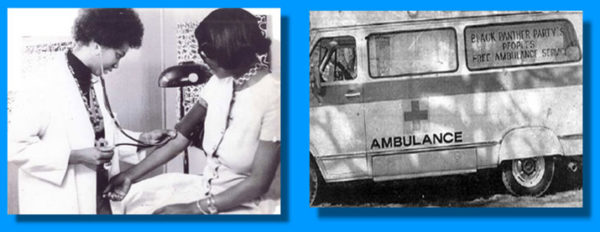

Health Clinics

The clinics were called People’s Free Medical Centers (PFMC) and eventually were established in 13 cities across the country, from Cleveland to New Haven, Connecticut; Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to Los Angeles. Women, according to sociologist Alondra Nelson, were the backbone of the effort —not surprising, considering that approximately 60 percent of Black Panther Party members were female. Some of the clinics were in storefronts, others in trailers or hastily built structures, and most did not last long. But they offered services such as testing for high blood pressure, lead poisoning, tuberculosis and diabetes; cancer detection screenings; physical exams; treatments for colds and flu; and immunization against polio, measles, rubella, and diphtheria. Nelson reports that many of the women and men involved in the PFMCs went on to become credentialed health care professionals.

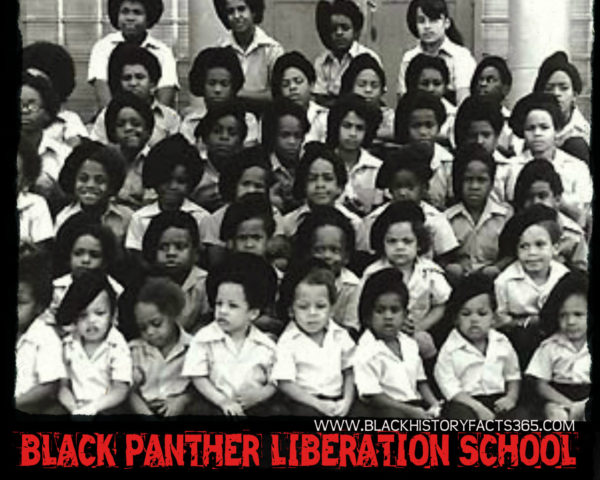

Youth Institute

The Intercommunal Youth Institute was established in January 1971 by the Black Panther Party. In 1974, the name was changed to Oakland Community School. The Black Panther Party goal was to get children to learn to their highest potential and to strengthen their minds so that one day they would be successful. The school graduated its first class in June 1974. In September 1977, California Gov. Edmund “Jerry” Brown Jr. and the California Legislature gave Oakland Community School a special award for “having set the standard for the highest level of elementary education in the state.”

Seniors Against a Fearful Environment (SAFE)

SAFE, a nonprofit corporation, was started by the Black Panther Party at the request of a group of senior citizens for the purpose of preventing muggings and attacks upon the elderly, particularly when they go out to cash their Social Security or pension checks. Prior to approaching the Black Panther Party, the seniors had gone to the Oakland Police Department to request protection. There the seniors were told that they “should walk close to the curb” in the future, according to a Panther report by David Hilliard, who served as the Party’s chief of staff. The program offered free transportation and escort services to the residents of the Satellite Senior Homes, a residential complex for the elderly in Oakland, California.

People’s Free Ambulance Service

The service provided free, rapid transportation for sick or injured people without time-consuming checks into the patients’ financial status or means. The People’s Free Ambulance Service operated with at least one ambulance on a 24-hour emergency basis, and from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on a nonemergency or convalescent basis, according to Hilliard. People were transported to and from the hospital or doctor’s office in a modern, comfortable ambulance by courteous, efficient and knowledgeable attendants.

Free Food Program

This program provided free food to Black and other oppressed people. The intent of the Free Food Program was to supplement the groceries of Black and poor people until economic conditions allowed them to purchase good food at reasonable prices, according to Hilliard. The Free Food Program provided two basic services to the community: 1. An ongoing supply of food to meet their daily needs. 2. Periodic mass distributions of food to reach a larger segment of the community than can be serviced from the ongoing supply. The community was provided with bags of fresh food containing items such as eggs, canned fruits and vegetables, chickens, milk, potatoes, rice, bread, cereal and so forth. A minimum of a week’s supply of food was included in each bag.

The Black Student Alliance

Founded in May 1972 when several Black student unions in the Bay Area pulled together with the goal of creating concrete programs on the campus that would unify the student body and Black students with the Black community. In order to make Bay Area colleges better serve and be more responsible to the surrounding poor and oppressed communities, the Black Student Alliance instituted a program for free books and supplies; a free transportation program; child care services; a financial aid program; a food program serving good, nutritious food at reasonable prices; and the initiation of relevant courses along with the demand for better instructors.

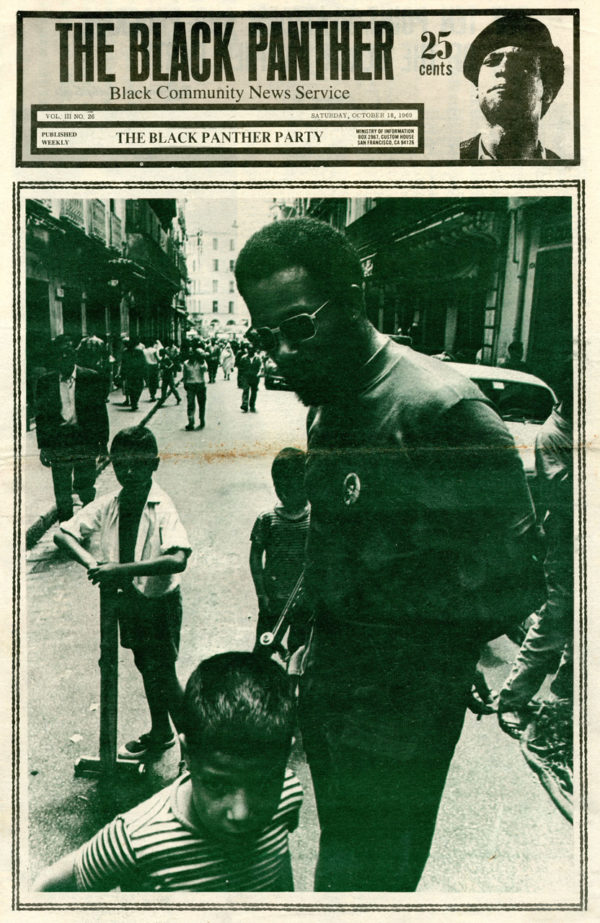

The Black Panther Newspaper

The paper was the official organ of the Black Panther Party. It was a tabloid-size newspaper that published regularly every week starting in April 1967. It was copyrighted by Huey P. Newton and was 24 pages, distributed nationally. The Black Panther provided news and information about the work of the Black Panther Party chapters throughout the country; news and news analysis of the Black and other oppressed communities in the United States, Africa and around the world; theoretical writings of party ideologists; and general news features on all matters relative to the liberation of humankind from oppression of any kind, according to chief of staff David Hilliard’s summary of Panther programs.

The Atlanta Black Star is one of the most relevant and newsworthy newspapers I've ever read.

Black History: day 15 - Cathay Williams, only Woman Buffalo Soldier

Cathay Williams

&f=1

Cathay Williams Only Woman Buffalo Soldier U.S. Army.

Born September 1844

Independence, Missouri

Died 1893 (aged 50–51)

Trinidad, Colorado

Nationality American

Other names John Williams, William Cathay

Occupation soldier, cook, seamstress

Employer U.S. government, self-employed

Military career

Allegiance United States of America

Years of service 1866-1868

Rank private

Unit 38th U.S. Infantry Regiment, U.S. Army (Buffalo soldier)

Cathay Williams (September 1844 – 1893) was an American soldier who enlisted in the United States Army under the pseudonym William Cathay. She was the first African-American woman to enlist, and the only documented to serve in the United States Army posing as a man.[1]

Contents

Early life

Williams was born in Independence, Missouri, to a free man and a woman in slavery, making her legal status also that of a slave. During her adolescence, Williams worked as a house slave on the Johnson plantation on the outskirts of Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1861 Union forces occupied Jefferson City in the early stages of the Civil War. At that time, captured slaves were officially designated by the Union as "contraband," and many were forced to serve in military support roles such as cooks, laundresses, or nurses. At age seventeen, Williams was pressed into serving the 8th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel William Plummer Benton.

American Civil War

For the next few years, Williams traveled with the 8th Indiana, accompanying the soldiers on their marches through Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia. Cathay Williams was present at the Battle of Pea Ridge and the Red River Campaign. At one time she was transferred to Little Rock, where she would have seen uniformed African-American men serving as soldiers, which may have inspired her own interest in military service. Later, Williams was transferred to Washington, D.C., where she served with General Philip Sheridan's command. When the war ended, Williams was working at Jefferson Barracks.

U.S. Army service

Despite the prohibition against women serving in the military, Cathay Williams enlisted in the United States Regular Army under the false name of "William Cathay"[2] on November 15, 1866, at St. Louis, Missouri, for a three-year engagement, passing herself off as a man. She was assigned to the 38th United States Infantry Regiment after she passed a cursory medical examination.[2] Only two others are known to have been privy to the deception, her cousin and a friend, both of whom were fellow soldiers in her regiment.

Shortly after her enlistment, Williams contracted smallpox, was hospitalized and rejoined her unit, which by then was posted in New Mexico. Possibly due to the effects of smallpox, the New Mexico heat, or the cumulative effects of years of marching, her body began to show signs of strain. She was frequently hospitalized. The post surgeon finally discovered she was a woman, and informed the post commander. She was discharged from the Army by her commanding officer, Captain Charles E. Clarke, on October 14, 1868.

Post-military service years

Cathay Williams went to work as a cook at Fort Union, New Mexico, and later moved to Pueblo, Colorado. Williams married, but it ended disastrously when her husband stole her money and a team of horses. Williams had him arrested. She next moved to Trinidad, Colorado, where she made her living as a seamstress. She may also have owned a boarding house. It was at this time that Williams' story first became public. A reporter from St. Louis heard rumors of an African-American woman who had served in the army, and came to interview her. Her life and military service narrative was published in The St. Louis Daily Times on 2 January 1876.

U.S. Army Pension records for Cathay Williams

In late 1889 or early 1890, Cathay Williams entered a local hospital where she remained for some time, and in June 1891, applied for a disability pension based on her military service. The nature of her illness and disability are unknown. There was precedent for granting a pension to female soldiers. Deborah Sampson in 1816, Anna Maria Lane, and Mary Hayes McCauley (better known as Molly Pitcher) had been granted pensions for their service in the American Revolutionary War.

Declining health and death

In September 1893, a doctor employed by the U.S. Pension Bureau examined Cathay Williams. Despite the fact that she suffered from neuralgia and diabetes, had had all her toes amputated, and could only walk with a crutch, the doctor decided she did not qualify for disability payments. Her application was rejected.[3][4]

The exact date of Williams' death is unknown, but it is assumed she died shortly after being denied a pension, probably sometime in 1893. Her simple grave marker would have been made of wood and deteriorated long ago. Thus her final resting place is now unknown.

Honors

In 2016, a bronze bust of Cathay Williams, featuring information about her and with a small rose garden around it, was unveiled outside the Richard Allen Cultural Center in Leavenworth, Kansas.[5]

In 2018, the Private Cathay Williams monument bench was unveiled on the Walk of Honor at the National Infantry Museum.[6]

"I don't need to do this!"

Finally. Something that Trump says that needs no fact checking.

Black History: day 16 - Mary Ellen Pleasant American Entrepreneur, Financier, Abolitionist

Mary Ellen Pleasant (19 August 1814 – 4 January 1904) was a successful 19th-century American entrepreneur, financier, real estate magnate and abolitionist whose life is shrouded in mystery. She identified herself as "a capitalist by profession" in the 1890 United States Census.[1] The press called her "Mammy" Pleasant but she did not approve, stating "I don't like to be called mammy by everybody. Put. that. down. I am not mammy to everybody in California." In her autobiography published in San Francisco's Pandex of the Press in January 1902, she stated her mother was a full blooded Louisiana negress and her father was a native Kanaka (Hawaiian), and when she was six years of age, she was sent to Nantucket to live with a Quaker woman named Hussey. She worked on the Underground Railroad across many states and then helped bring it to California during the Gold Rush Era. She was a friend and financial supporter of John Brown, and was well known in abolitionist circles. After the Civil War, she took her battles to the courts in the 1860s and won several civil rights victories, one of which was cited and upheld in the 1980s and resulted in her being called "The Mother of Human Rights in California".[2]

Early years

Pleasant made contradictory claims about her earliest years, and her exact origin remains unclear.[2] Her birthday is known to be August 19, but the year is in dispute. Her gravestone at Tulocay Cemetery in Napa, California, states 1812, although most sources list her birth as 1814.[3] In one version of her memoirs dictated to her god-daughter Charlotte Downs, she claimed she was born a slave to a Voodoo priestess and John Hampden Pleasants, youngest son of Governor of Virginia James Pleasants. In any case, she showed up in Nantucket, Massachusetts circa 1827 as a 10- to 13-year-old bonded servant to a storekeeper, "Grandma" Hussey. She worked out her bondage, then became a family member and lifelong friend to Hussey's granddaughter Phoebe Hussey Gardner. The Husseys were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement, and Pleasant met many of the famous abolitionists.

Career and marriages

With the support of the Hussey/Gardners, she often passed as white. Pleasant married James Smith, a wealthy flour contractor and plantation owner who had freed his slaves and was also able to pass as white. She worked with Smith as a "slave stealer" on the Underground Railroad until his death about four years later. They transported slaves to northern states such as Ohio and even as far as Canada. Smith left instructions and money for her to continue the work after his death.

She began a partnership with John James ("J.J."![]() Pleasants circa 1848. Although no official records exist of their marriage, it was probably conducted by their friend Captain Gardner, Phoebe's husband, aboard his boat. They continued Smith's work for a few more years, when increasing attention from slavers forced a move to New Orleans. J.J. Pleasants appears to have been a close relative of Marie Laveau's husband, and there is some indication that Pleasant and Laveau met and consulted many times before Pleasant left New Orleans by boat for San Francisco in April 1852. J. J. had gone ahead and written back that the area seemed promising for the Underground Railroad.

Pleasants circa 1848. Although no official records exist of their marriage, it was probably conducted by their friend Captain Gardner, Phoebe's husband, aboard his boat. They continued Smith's work for a few more years, when increasing attention from slavers forced a move to New Orleans. J.J. Pleasants appears to have been a close relative of Marie Laveau's husband, and there is some indication that Pleasant and Laveau met and consulted many times before Pleasant left New Orleans by boat for San Francisco in April 1852. J. J. had gone ahead and written back that the area seemed promising for the Underground Railroad.

When Mary Ellen arrived in San Francisco, she passed as white, using her first husband's name among the whites, and took jobs running exclusive men's eating establishments, starting with the Case and Heiser. She met most of the founders of the city as she catered lavish meals, and she benefited from the tidbits of financial gossip and deals usually tossed around at the tables. She engaged a young clerk, Thomas Bell, at the Bank of California and they began to make money based on her tips and guidance. Thomas made money of his own, especially in quicksilver, and by 1875 they had amassed a 30 million dollar fortune (roughly 647 million dollars in 2017[4]) between them. J.J., who had worked with Mary Ellen from the slave-stealing days to the civil rights court battles of the 1860s and '70s, died in 1877 of diabetes.

Mary Ellen did not conceal her race from other blacks, and was adept at finding jobs for those brought in by Underground Railroad activities. Some of the people she sponsored became important black leaders in the city. She left San Francisco from 1857 to 1859 to help John Brown. She was said to have actively supported his cause with money and work. There was a note from her in his pocket when he was arrested after the Harpers Ferry Armory incident, but as it was only signed with the initials "MEP" (which were misread as "WEP"![]() . She was not caught. She returned to San Francisco to continue her work there, where she was known as the "Black City Hall".[5]

. She was not caught. She returned to San Francisco to continue her work there, where she was known as the "Black City Hall".[5]

After the Civil War, Pleasant publicly changed her racial designation in the City Directory from "White" to "Black", causing a little stir among some whites. She began a series of court battles to fight laws prohibiting blacks from riding trolleys and other such abuses.

Suing over streetcar segregation

Pleasant successfully attacked racial discrimination in San Francisco public conveyances after she and two other black women were ejected from a city streetcar in 1866. She filed two lawsuits. The first, against the Omnibus Railroad Company, was withdrawn after the company promised to allow African-Americans to board their streetcars.[6]:51 The second case, Pleasant v. North Beach & Mission Railroad Company, went to the California Supreme Court and took two years to complete. In the city, the case outlawed segregation in the city's public conveyances.[7] However, at the State Supreme Court, the damages awarded against her at the trial court were reversed and found excessive.[6]:54

Later life

Later in life, a series of court battles with Sarah Althea Hill, Senator William Sharon, and the family of business associate Thomas Bell, including his widow Teresa Bell and his son Fred Bell, damaged Pleasant's reputation and cost her resources and wealth. Pleasant died in San Francisco, California on January 4, 1904 in poverty.

Late in life, she was befriended by Olive Sherwood, and she was buried in the Sherwood family plot in Tulocay Cemetery, Napa, California. Her gravesite is marked with a metal sculpture that was dedicated on June 11, 2011 .[8]

Posthumous recognition

Pleasant has been featured or mentioned in several works of fiction. Michelle Cliff's 1993 book "Free Enterprise" is subtitled "A Novel of Mary Ellen Pleasant" and features her abolitionist activities.[9] The ghost of Mary Ellen Pleasant is a character in the 1997 novel Earthquake Weather, by Tim Powers. Karen Joy Fowler's historical novel Sister Noon, published in 2001, features Pleasant as a central character, and Thomas Bell and Teresa Bell as secondary characters.[10]

Pleasant has also been discussed in film and television. The 2008 documentary Meet Mary Pleasant covered her life,[11] and a segment of a 2013 episode of the Comedy Central series Drunk History covered Pleasant's life.[12] Pleasant was portrayed by Lisa Bonet.

In 1974, the city of San Francisco designated eucalyptus trees that Pleasant had planted outside her mansion at the southwest corner of Octavia and Bush streets in San Francisco as a Structure of Merit.[13] The trees and associated plaque are now known as Mary Ellen Pleasant Memorial Park, which is the smallest park in San Francisco.[14] Her burial site has been designated a "Network to Freedom" site by the National Park Service.[8]

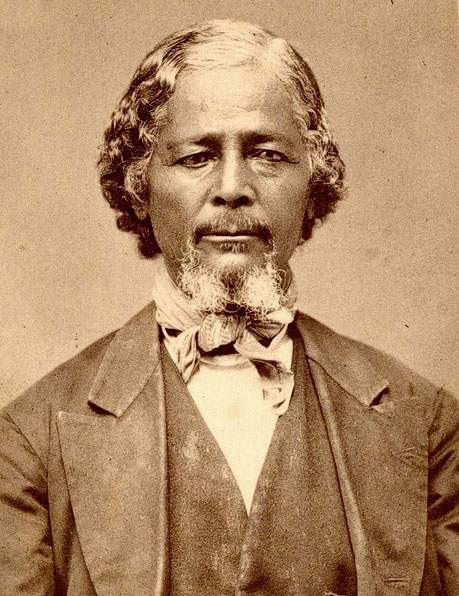

Black History: day 12 - Benjamin "Pap" Singleton (1809-1900) American activist and businessma

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_%22Pap%22_Singleton

Benjamin "Pap" Singleton (1809–1900) was an American activist and businessman best known for his role in establishing African American settlements in Kansas. A former slave from Tennessee who escaped to freedom in 1846, he became a noted abolitionist, community leader, and spokesman for African-American civil rights. He returned to Tennessee during the Union occupation in 1862, but soon concluded that blacks would never achieve economic equality in the white-dominated South. After the end of Reconstruction, Singleton organized the movement of thousands of black colonists, known as Exodusters, to found settlements in Kansas. A prominent voice for early black nationalism, he became involved in promoting and coordinating black-owned businesses in Kansas and developed an interest in the Back-to-Africa movement.

Early life and education

Although it is known that Benjamin Singleton was born in 1809 into slavery in Davidson County near Nashville, Tennessee, details of his early life remain scant. He was the son of a white father and an enslaved black mother. As a youth, he was trained as a carpenter but regretted never learning to read and write. Reportedly Singleton made several attempts to run away but was unsuccessful.

In 1846 Singleton managed to escape to freedom. Singleton made his way north along the Underground Railroad to Windsor, Ontario, and remained there a year before relocating to Detroit, Michigan. In Detroit he lived as a scavenger and used what resources he could to help other escaped slaves find their way to freedom in Canada. Singleton remained in Detroit until after the Civil War had been underway. During this time, he worked as a carpenter.

Separatism

After the Union Army occupied Middle Tennessee in 1862, Singleton returned and took up residence in Nashville, Tennessee, and worked as a cabinetmaker and coffin maker.[1] The experiences of freedmen subject to racial violence and political problems led Singleton to conclude that blacks would have no chance for equality in the South. Disgusted by political leaders who failed to deliver on promises of equality for freedmen, in 1869 Singleton joined forces with Columbus M. Johnson, a black minister in Sumner County, and began looking for ways to establish black economic independence.

In 1874, Singleton and Johnson founded the Edgefield Real Estate Association with the goal of helping African Americans obtain land in the Nashville area. Unfortunately, white landowners were unwilling to bargain with them and wanted too high prices for their land. Convinced that freedmen must leave the South to achieve true economic independence, in 1875 Singleton began to explore the idea of planting black colonies in the American West. His real estate organization was renamed the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association. In 1876 Singleton and Johnson traveled to Kansas to scout land in Cherokee County in the southeastern corner of the state. Heartened by what he saw, Singleton returned to Nashville and began recruiting settlers for a proposed colony.

Singleton Colonies

In the summer of 1877, Singleton led approximately seventy-three black settlers to Cherokee County near the town of Baxter Springs.[2] Once the settlers arrived, they began negotiating with the Missouri River, Fort Scott, and Gulf Railroad for land to build their proposed Singleton Colony. Unfortunately, rich lead deposits had been discovered in the area the previous year, which led to a mining boom and caused land prices to rise too high. Without the ability to buy land, they could not create a colony in Cherokee County. Singleton began looking elsewhere.

Singleton began looking for government land which his settlers could acquire through the 1862 Homestead Act. He found some available land on what had been the former Kaw Indian Reservation near the town of Dunlap, Kansas, on the borders of Morris County and Lyon County. Dunlap was situated along the tracks of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, familiarly called the Katy Railroad. The land was marginal, but in the spring of 1878, Singleton's settlers left middle Tennessee for Kansas via steamboats on the Cumberland River. The following year they officially established the Dunlap Colony.[2] More than 2400 settlers emigrated from the Nashville and Sumner County areas.[1] Most settlers lived in dugouts during their first year on the Great Plains. They stuck it out and made the colony a success.

Exodusters, 1879-80

By 1879 of the "Great Exodus", 50,000 freedmen known as Exodusters had migrated from the South to escape poverty and racial violence following whites' regaining political control across the former Confederacy. They migrated to Kansas, Missouri, Indiana and Illinois seeking land, better working conditions and the chance to live in peace. Part of Topeka, Kansas, was known as "Tennessee Town" because of many migrants from that state. Most had no direct connection with Singleton's organized colony movement, but Singleton and his followers were sympathetic to their plight. Many white Kansans began to object to the arrival of so many desperately poor blacks into their state. Singleton stepped forward to defend the Exodusters' right to try to make better lives in the American West.

In 1880 Singleton was requested to appear before the United States Senate in Washington, D.C., to testify on the causes of the Great Exodus to Kansas. Singleton rebuffed the efforts of southern Senators to discredit the Exodus Movement. He testified to his own success in setting up independent black colonies and noted the terrible conditions which caused freedmen to leave the South. Singleton returned to Kansas as a nationally recognized spokesman for the Exodusters. Unfortunately, the arrival of so many poor blacks put more of a financial burden on the Dunlap Colony than the original settlers could bear. By 1880, the Presbyterian Church had taken charitable control of the settlement and made plans to build a Freedmen's Academy in the town. Singleton had no more dealings with his colony at Dunlap.

Final years

In 1881, Benjamin Singleton was 72 years old, and most people referred to him affectionately as "old Pap." He was still a formidable figure and used his reputation to bring together blacks into an organization called the Colored United Links (CUL). The goal of the CUL, which he created in Topeka, Kansas, was to combine the financial resources of all black people to build black-owned businesses, factories, and trade schools. The CUL formed in 1881 and held several conventions. The organization was successful enough locally that Republican Party officials in Kansas became interested in its potential political strength. Presidential candidate James B. Weaver of the Greenback Party met with CUL leaders, to discuss fusion between the two groups. After 1881, CUL membership faltered, however, and the organization soon fell apart.

After the failure of the CUL, Singleton became convinced that blacks would never be allowed to succeed in the United States. In 1883 Singleton briefly joined with St. Louis, Missouri, businessman Joseph Ware and black minister John Williams in proposing that blacks migrate to the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. That idea did not develop. In 1885 Singleton moved to Kansas City where he began to organize around Pan-Africanism. In 1885 Singleton founded the United Transatlantic Society (UTS) with the goal of having all blacks relocate from the United States to Africa. This was a time when Bishop Henry McNeil Turner had his own proposed African migration movement.

The UTS lasted till 1887 but never managed to send anyone to Africa. In poor health, Singleton retired from his life of activism. He raised his voice one final time in 1889 to call for a portion of the newly opening Oklahoma Territory to be reserved as an all-black state.

Benjamin Singleton died on February 17, 1900, in Kansas City, Missouri.[3][4][5] He was buried in Union Cemetery, Kansas City, Missouri on February 26, 1900.[6][7]

Family

Benjamin Singleton was the father of several children. Two of his children – Emily, born about 1840 in Tennessee, and Sarah, born about 1858 in Michigan – wrote letters to their father from East Nashville, Tennessee, during the mid-1880s.[8] An undated note regarding Singleton’s testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee in 1880 quoted Singleton as saying: “I have been a slave fled to Canada when my children were small and nineteen years after when I returned they were grown. ”[9]

His son, Joshua S eventually settled in Allensworth, California, a black agricultural settlement in Tulare County. Joshua's grandchildren through his daughter Virginia Louise Williams were John Williams Jr., Midge Williams (1915-1952), Charles and Robert, who started singing together in the Bay Area as the Williams Quartette. In 1928 they started touring as the Williams Four. In 1933 they had a successful tour in Shanghai, China and Japan. Midge Williams also sang as a swing jazz soloist in the late 1930s and 1940s. She recorded with a group as Midge Williams and Her Jazz Jesters.[10] In 2002, American scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed "Pap" Singleton on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[11] According to Joshua W. Singleton’s 1928 Tulare County, California death certificate his father’s name is indicated as “Washington Singleton,” born Mississippi. Joshua’s mother’s name is indicated as “unknown.” (Joshua W. Singleton born April 1, 1866, Mississippi, died May 4, 1928.) [12]

Florida's Prisoners Are Getting Screwed Out of $11 Million of Music They Purchased

Florida's Prisoners Are Getting Screwed Out of $11 Million of Music They Purchased

A new multimedia tablet program means that inmates will be unable to keep the mp3s and players they purchased under a previous for-profit program.

https://noisey.vice.com/en_us/article/pawmjn/floridas-prisoners-are-getting-screwed-out-of-dollar11-million-of-music-they-purchased

There are precious few comforts available to those trapped within the American prison industrial complex, and the Department of Corrections' continuing push towards privatization means that even the scarce options currently available are becoming untenable for most folks behind the walls. In just one example, New Yorkers saw this happen in our own backyard earlier this year, when Gov. Cuomo attempted to implement a pilot program to privatize prison care packages—only to rescind it after a massive public outcry against the cruel proposal.

Further South, inmates in Florida—whose sprawling prison system is notoriously violent, and plagued by reports of racism—are being adversely affected by the state DOC's efforts to "modernize" their cages by striking a profit-driven deal with private company JPay to introduce multimedia tablets. Inmates there had had access to entertainment technology since 2011, when the DOC partnered with another private company, Access Corrections, to sell various models of mp3 players which incarcerated people could use to download songs (for $1.70 a pop). Now, they’ll have the opportunity to try out something new—but that opportunity comes at a hefty price.

As Ben Conarck of the Florida Times-Union reports, the main problem with these new tablets—besides the fact that they are going to be used to generate profit off the backs of the incarcerated and their loved ones—is that, in order to participate in the new tablet program, inmates will be forced to return the mp3 players that they had already bought, and will be unable to transfer over the mp3s they've already purchased to the new tablets. Sales of the Access Corrections mp3 players ended back in August 2017. Patrick Manderfield, spokesman for the DOC explained that the songs cannot be transferred because the “devices/services are provided by two different vendors.” Perhaps more interestingly, according Timothy Hoey, the assistant warden at Homestead Correctional Institution, “the download of content purchased from one vendor to another vendor’s device would negate the new vendor’s ability to be compensated for their services.”

Advertisement

The Florida DOC is effectively robbing its incarcerated population of music that they and their loved ones have already paid for, to the tune of $11.3 million ($1.4 million of which in commissions on song downloads and related sales has been collected by the DOC and sent to the state’s General Revenue fund since July 2011). (This number reflects the total amount of music purchased since the program's implementation in 2011.) Hundreds of incarcerated folks have flooded the DOC with complaints about the new system, but the DOC's response to the kerfuffle has been less than generous.

The Department suggests that inmates send their devices and music home if they want to keep them (after paying an additional $25 fee to unlock the mp3 player and download their music onto a CD), and points to a deal they'd made with Access Corrections to allow inmates to keep their devices if they choose not to participate in the tablet program. Bearing in mind that said tablet program is being touted as offering "educational opportunities" and a way to connect with their families, that's a difficult choice to make— between keeping one's possessions but being deprived of potentially useful technology, or giving up one of one's only sources of entertainment (and abandoning a significant financial investment) in favor of an unknown, profit-driven program.

The Department told inmates that they are “aware that family members over the years have provided funds to their loved ones to add music to their current MP3 player. It is unfortunate that the music cannot be transferred, however, we hope that overtime [sic] the family and the inmate will see the added value of the new program.”

Advertisement

"Unfortunate" is certainly one way to describe it. "Predatory and inhumane" is another, but welcome to another day in mass incarcerated America. With the upcoming August 21 national prison strike looming and this year’s Operation PUSH Florida prison strike fresh in their minds, one wonders how the incarcerated workers of Florida are feeling about this latest slight.

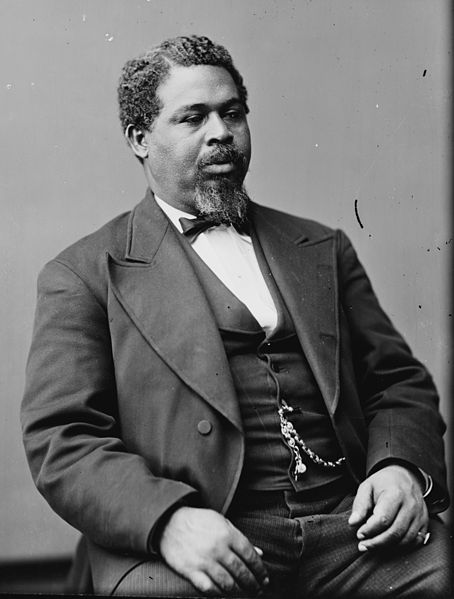

Black history: day 12 - Robert Smalls, desperate times/desperate measures

Robert Smalls (April 5, 1839 – Feb. 23, 1915)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Smalls

17 battles including

Battle of Simmon's Bluff

Second Battle of Pocotaligo

Second Battle of Fort Sumter

Sherman's March to the Sea

Robert Smalls (April 5, 1839 – February 23, 1915) was an American who escaped slavery to freedom and became a ship's pilot, sea captain, and politician. He freed himself, his crew and their families from slavery during the American Civil War by commandeering a Confederate transport ship, CSS Planter, in Charleston harbor, on May 13, 1862, and sailing it from Confederate-controlled waters of the harbour to the U.S. blockade that surrounded it. His example and persuasion helped convince President Abraham Lincoln to accept African-American soldiers into the Union Army and the Navy.

Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina. After the American Civil War, he returned there and became a politician, winning election as a Republican to the South Carolina State legislature and the United States House of Representatives during the Reconstruction era. Smalls authored state legislation providing for South Carolina to have the first free and compulsory public school system in the United States. He founded the Republican Party of South Carolina. Smalls was the last Republican to represent South Carolina's 5th congressional district until 2010.

Contents

Early life

Robert Smalls was born in 1839 to Lydia Polite, a woman enslaved by Henry McKee, who was most likely Smalls' father.[1] She gave birth to him in a cabin behind McKee's house, on 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, South Carolina.[2] He grew up in the city under the influence of the Lowcountry Gullah culture of his mother. His mother lived as a servant in the house but grew up in the fields. Robert was favored over other slaves, so his mother worried that he might grow up not understanding the plight of field slaves, and asked for him to be made to work in the fields and to witness whipping.[3]

When he was 12, at the request of his mother, Smalls' master sent him to Charleston to hire out as a laborer for one dollar a week, with the rest of the wage being paid to his master. The youth first worked in a hotel, then became a lamplighter on Charleston's streets. In his teen years, his love of the sea led him to find work on Charleston's docks and wharves. Smalls worked as a longshoreman, a rigger, a sail maker, and eventually worked his way up to become a wheelman, more or less a pilot, though slaves were not honored by that title. As a result, he was very knowledgeable about Charleston harbor.[4]

At age 17, Smalls married Hannah Jones, an enslaved hotel maid, in Charleston on December 24, 1856. She was five years his senior and already had two daughters. Their own first child, Elizabeth Lydia Smalls, was born in February 1858. Three years later they had a son, Robert Jr., who later died aged two.[5] Robert aimed to pay for their freedom by purchasing them outright, but the price was steep, $800 (equivalent to $22,308 in 2018). He had managed to save up only $100. It could take decades for him to reach $800.[3]

Escape from slavery

In April 1861, the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter in nearby Charleston Harbor. In the fall of 1861, Smalls was assigned to steer the CSS Planter, a lightly armed Confederate military transport under the command of Charleston's District Commander Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley.[6] Planter's duties were to deliver dispatches, troops and supplies, to survey waterways, and to lay mines. Smalls piloted the Planter throughout Charleston harbor and beyond, on area rivers and along the South Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts.[7][8] From Charleston harbor, Smalls and the Planter's crew could see the line of Federal blockade ships in the outer harbor, seven miles away.[9] Smalls appeared content and had the confidence of the Planter's crew and owners, and at some time in April 1862, Smalls began to plan an escape. He discussed the matter with the other slaves in the crew except one, whom he did not trust.[2]

The day of May 12, 1862, the Planter traveled ten miles southwest of Charleston to stop at Coles Island, a Confederate post on the Stono River that was being dismantled.[10] There the ship picked up four large guns to transport to a fort in Charleston harbor. Back in Charleston, the crew loaded 200 pounds of ammunition and 20 cords of firewood onto the Planter.[7] At some point family members hid aboard another steamer docked at the North Atlantic wharf.[11][12]

On the evening of May 12, Planter was docked as usual at the wharf below General Ripley's headquarters.[2] Her three white officers disembarked to spend the night ashore, leaving Smalls and the crew on board, "as was their custom."[13] (Afterward, the three Confederate officers were court-martialed and two convicted, but the verdicts were later overturned.[2]) About 3 a.m. May 13, Smalls and seven of the eight slave crewmen made their previously planned escape to the Union blockade ships. Smalls put on the captain's uniform and wore a straw hat similar to the captain's. He sailed the Planter past what was then called Southern Wharf, and stopped at another wharf to pick up his wife and children, and the families of other crewmen.

Smalls guided the ship past the five Confederate harbor forts without incident, as he gave the correct signals at checkpoints. The Planter had been commanded by a Captain Charles C.J. Relyea and Smalls copied Relyea’s manners and straw hat on deck to fool Confederate onlookers from shore and the forts.[14] The Planter sailed past Fort Sumter at about 4:30 a.m. The alarm was only raised by the time they were out of gun range. Smalls headed straight for the Union Navy fleet, replacing the rebel flags with a white bed sheet his wife had brought aboard. The Planter had been seen by the USS Onward, which was about to fire until a crewman spotted the white flag.[4] In the dark, the sheet was hard to see, but the sunrise came just in time.[3]

Witness account:

"Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, 'I see something that looks like a white flag'; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and 'de heart of de Souf,' generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, 'Good morning, sir! I've brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!'" That man was Robert Smalls.[3]

The Onward's captain, John Frederick Nickels,[14] boarded the Planter, and Smalls asked for a United States flag to display. He surrendered the Planter and her cargo to the United States Navy.[4] Smalls' escape plan had succeeded.

The Planter and description of Smalls' actions were forwarded by Lt. Nickels to his commander, Capt. E.G. Parrott. In addition to her own light guns, Planter carried the four loose artillery pieces from Coles Island and the 200 pounds of ammunition. Most valuable, however, were the captain's code book containing the Confederate signals, and a map of the mines and torpedoes that had been laid in Charleston's harbor. Smalls' own extensive knowledge of the Charleston region's waterways and military configurations proved highly valuable. Parrott again forwarded the Planter to flag officer Du Pont at Port Royal, describing Smalls as very intelligent. Smalls gave detailed information about Charleston's defenses to Du Pont, commander of the blockading fleet. Federal officers were surprised to learn from Smalls that contrary to their calculations, only a few thousand troops remained to protect the area, the rest having been sent to Tennessee and Virginia. They also learned that the Coles Island fortifications on Charleston's southern flank were being abandoned and were without protection.[7] This intelligence allowed Union forces to capture Coles Island and its string of batteries without a fight on May 20, a week after Smalls' escape. The Union would hold the Stono inlet as a base for the remaining three-years of the war.[2] Du Pont was impressed, and wrote the following to the Navy secretary in Washington: "Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feet so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest." He "is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been."[3]

Service to the Union

Smalls, having just turned 23, quickly became known in the North as a hero for his daring exploit. Newspapers and magazines reported his actions. The U.S. Congress passed a bill awarding Smalls and his crewmen the prize money for the Planter (valuable not only for its guns but low draft in Charleston bay); Southern newspapers demanded harsh discipline for the Confederate officers whose joint shore leave had allowed the slaves to steal the boat.[15] Smalls's share of the prize money came to US$1,500 (equivalent to $37,645 in 2018). Immediately after the capture, Smalls was invited to travel to New York to help raise money for ex-slaves, but Admiral DuPont vetoed the proposal and Smalls began to serve the Union Navy, especially with his detailed knowledge of mines laid near Charleston. However, with the encouragement of Major General David Hunter, the Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to Washington, D.C., in August 1862 with Rev. Mansfield French, a Methodist minister who had helped found Wilberforce University in Ohio and had been sent by the American Missionary Association to help former slaves at Port Royal.[16] They wanted to persuade Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to permit black men to fight for the Union. Although Lincoln had previously rescinded orders by Hunter and Generals Fremont and Sherman to mobilize black troops,[16] Stanton soon signed an order permitting up to 5,000 African Americans to enlist in the Union forces at Port Royal. Those who did were organized as the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Regiments (Colored). Smalls worked as a civilian with the Navy until March 1863, when he was transferred to the Army. By his own account, Smalls was present at 17 major battles and engagements in the Civil War.[2]

After capture, the Planter required some repairs, which were performed locally, and went into Union service near Fort Pulaski. The boat was valued for its shallow draft, compared to other boats in the fleet.[17] Smalls was made pilot of the Crusader under Captain Alexander Rhind. In June of that year, Smalls was piloting the Crusader on Edisto in Wadmalaw Sound when the Planter returned to service, and an infantry regiment engaged in the Battle of Simmon's Bluff at the head of the Edisto River. He continued to pilot the Crusader and the Planter. As a slave, he had assisted in laying mines (then called "torpedoes"

He was made pilot of the ironclad USS Keokuk, again under captain Rhind, and took part in the attack on Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863, which was a preamble to the Second Battle of Fort Sumter later that fall. The Keokuk took 96 hits and retired for the night, sinking the next morning. Smalls and much of the crew moved to the Ironside and the fleet returned to Hilton Head.[14]

In June 1863, David Hunter was replaced as commander of the Department of the South by Quincy Adams Gillmore. With Gillmore's arrival, Smalls was transferred to the quartermaster's department. Smalls was pilot of the USS Isaac Smith, later recommissioned in the Confederate Navy the Stono in the expedition on Morris Island. When Union troops took the south end of the Island, Smalls was put in charge of the Light House Inlet as pilot.[14]

On December 1, 1863, Smalls was piloting the Planter under Captain James Nickerson on Folly Island Creek when Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened. Nickerson fled the pilot house for the coal-bunker. Smalls refused to surrender, fearing that the black crewmen would not be treated as prisoners of war and might be summarily killed. Smalls entered the pilothouse and took command of the boat and piloted her to safety. For this, he was reportedly promoted by Gillmore to the rank of captain and made acting captain of the Planter.[14][4]

In May 1864, he was voted an unofficial delegate to the Republican National Convention in Baltimore. Later that spring, Smalls piloted the Planter to Philadelphia for an overhaul. In Philadelphia, he supported what was known as the Port Royal Experiment, an effort to raise money to support the education and development of ex-slaves. At the outset of the civil war, Smalls could not read or write, but he achieved literacy in Philadelphia. In 1864, Smalls was in a streetcar in Philadelphia and was ordered to give his seat to a white passenger. Rather than ride on the open overflow platform, Smalls left the car. This incident of humiliating a heroic veteran was cited in the debate that resulted in the legislature's passing a bill to integrate public transportation in Pennsylvania in 1867.[2]

In December 1864, Smalls and the Planter moved to support William T. Sherman's army in Savannah, Georgia, at the destination point of his March to the Sea. Smalls returned with the Planter to Charleston harbor in April 1865 for the ceremonial raising of the American flag again at Fort Sumter.[2] Smalls was discharged on June 11, 1865. Other vessels Smalls piloted during the war include the Huron and the Paul Jones.[18] He continued to pilot the Planter, serving a humanitarian mission of taking food and supplies to freedmen who lost their homes and livelihoods during the war. On September 30, the Planter entered the service of the Freedmen's Bureau.[19]

Commission and prize money

Smalls' position in the Union Army and Navy has been disputed and Smalls' reward for the capture of the Planter has been criticized. During Smalls' life, articles about Smalls state that when he was assigned to pilot the Planter, the Navy did not allow him to hold the rank of pilot because he was not a graduate of a naval academy, a requirement at that time. To assure he received proper pay for a captain, he was commissioned second lieutenant of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (later re-designated as the 33rd US Colored Infantry) and detailed to act as pilot. Many sources also state that General Gillmore promoted Smalls to captain in December 1863 when he saved the Planter when it was under attack near Secessionville.[20] Later sources state that Smalls did receive a commission either in the Army or the Navy, but he was likely officially a civilian throughout the war.[2]

Later in his life, when Smalls sought a Navy pension, he learned that he had not been officially commissioned. He claimed he had received an official commission from Gillmore but had lost it. In 1883, a bill passed committee to put him on the Navy retired list, but in the end was halted, allegedly due to Smalls' being black.[21] In 1897, a special act of congress granted Smalls a pension of $30 per month, equal to the pension for a Navy captain.[2]

In 1883, during discussion of the bill to put Smalls on the Navy retired list, a report stated that the 1862 appraisal of the Planter was "absurdly low" and that a fair valuation would have been over $60,000. However, Smalls received no further payment until 1900. That year, Congress passed a statute paying Smalls $5,000 less the amount paid to him in 1862 ($1,500) for his capture of the steamship. Many still felt that this was less than his due.[2]

After the Civil War

Immediately following the war, Smalls returned to his native Beaufort, where he purchased his former master's house at 511 Prince St, which Union tax authorities had seized in 1863 for refusal to pay taxes. Later, the former owner sued to regain the property, but Smalls retained ownership in the court case. The case became an important precedent in other, similar cases.[2] His mother, Lydia, lived with him for the remainder of her life. He allowed his former master's wife, the elderly Jane Bond McKee, to move into her former home prior to her death. Smalls spent nine months learning to read and write. He purchased a two-story Beaumont building to use as a school for African-American children.[19]

Business ventures

In 1866 Smalls went into business in Beaufort with Richard Howell Gleaves, a businessman from Philadelphia. They opened a store to serve the needs of freedmen. Smalls also hired a teacher to help him study.[18] That April, the Radical Republicans who controlled Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson's vetoes and passed a Civil Rights Act. In 1868, they passed the 14th Amendment, which was ratified by the states to extend full citizenship to all Americans regardless of race.

Smalls invested significantly in the economic development of the Charleston-Beaufort region. In 1870, in anticipation of a Reconstruction-based prosperity, Smalls, with fellow representatives Joseph Rainey, Alonzo Ransier and others, formed the Enterprise Railroad, an 18-mile horse-drawn railway line that carried cargo and passengers between the Charleston wharves and inland depots.[22] Except for one white director,[23] the railroad's board of directors was entirely African American. Richard H. Cain was its first president. Author Bernard E. Powers describes it as "the most impressive commercial venture by members of Charleston's black elite."[24][25] He owned and helped publish a black-owned newspaper, the Beaufort Southern Standard starting in 1872.[19]

Political affiliation

Smalls was a loyal Republican. On August 22, 1912, he wrote to U.S. Senator Knute Nelson, "I never lose sight of the fact that had it not been for the Republican Party, I never would have been an office-holder of any kind—from 1862 to the present."[26] In words that became famous, he described his party as "the party of Lincoln ... which unshackled the necks of four million human beings". He wrote this line on September 12, 1912, in a letter expressing his anxiety over the looming presidential election.[27] He concluded that letter, "I ask that every colored man in the North who has a vote to cast, would cast that vote for the regular Republican Party and thus bury the Democratic Party so deep that there will not be seen even a bubble coming from the spot where the burial took place."[28]

State politics

Smalls was a delegate at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention where he was a part of the effort to make free, compulsory schooling available to all South Carolina children.[19] He also served as a delegate at several Republican National Conventions; he also participated in the South Carolina Republican State conventions.

In 1868, Smalls was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He was very effective, and introduced the Homestead Act and introduced and worked to pass the Civil Rights bill. In 1870, Jonathan Jasper Wright was elected judge of the South Carolina Supreme Court and Smalls was elected to fill his unexpired time in the Senate. He continued in the Senate, winning the 1872 election against W. J. Whipper. In the senate he was considered a very good speaker and debater. He was on the Finance Committee and chairman of the Public Printing Committee.[29][19]

He was a delegate to the National Republican Conventions in 1872 in Philadelphia, which nominated Grant for president; and in 1876 in Cincinnati, which nominated Hayes; and in 1884 in Chicago, which nominated Blaine[29]—and then continuously to all conventions until 1896.[30] He was also elected vice-president of the South Carolina Republican Party at their 1872 state convention.

In 1873, he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Third Regiment, South Carolina State Militia. He was later promoted to brigadier-general of the Second Brigade, South Carolina Militia, and the major-general of the Second Division, South Carolina State Militia. He held this position until 1877, when Democrats took control of the state government.[29][19]

National politics

In 1874, Smalls was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served two terms from 1875 to 1879. From 1882 to 1883 he represented South Carolina's 5th congressional district in the House. The state legislature gerrymandered to change the district boundaries, including Beaufort and other heavily black, coastal areas in South Carolina's 7th congressional district, giving the others substantial white majorities. Smalls was elected from the 7th district and served from 1884 to 1887. He was a member of the 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th, 49th U.S. Congresses.[2]

In 1875, he opposed the transfer of troops out of the South, fearing the effect of such a move on the safety of blacks in the South.[18] During consideration of a bill to reduce and restructure the United States Army, Smalls introduced an amendment that "Hereafter in the enlistment of men in the Army ... no distinction whatsoever shall be made on account of race or color." However, the amendment was not considered by Congress. He was the last Republican elected from the 5th district until 2010 when Mick Mulvaney took office. He was the second-longest serving African-American member of Congress (behind his contemporary Joseph Rainey) until the mid-20th century.[2]

After the Compromise of 1877, the U.S. government withdrew its remaining forces from South Carolina and other Southern states. Conservative Southern Bourbon Democrats, who called themselves the Redeemers, had resorted to violence and election fraud to regain control of the state legislature. As part of wide-ranging white efforts to reduce African-American political power, Smalls was charged and convicted of taking a bribe five years earlier in connection with the awarding of a printing contract. He was pardoned as part of an agreement by which charges were also dropped against Democrats accused of election fraud.[30]

The scandal took a political toll, and he was defeated by Democrat George D. Tillman in the senate election in 1878, and again, narrowly, in 1880. He successfully contested the 1880 result and regained the seat in 1882. In 1884 he was elected to fill a seat in a different district. He was nominated for Senate but defeated by Wade Hampton in 1886. During this period in Congress he supported racial integration legislation, supported a pension for the widow of his former Major General, David Hunter, and advised South Carolina blacks to refrain from emigrating to the North and Midwest or to Liberia.[18]

In 1890 he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as collector of the Port of Beaufort, which he held until 1913 except during Democrat Grover Cleveland's second term.[2] Smalls was active into the twentieth century. He was a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention. Together with five other black politicians, he strongly opposed white Democratic efforts that year to disfranchise black citizens. They wrote an article for the New York World to publicize the issues, but the state constitution was ratified. It and similar constitutions across the South for some time passed challenges that reached the US Supreme Court, resulting in the exclusion of African Americans from politics across the South and crippling of the Republican Party in the region.

In the late 1890s he began to suffer from diabetes. He turned down an offer of a colonelcy of a black regiment in the Spanish–American War and to the post of minister to Liberia.

Local politics

Though Smalls was not officially involved with politics on the local level, he did, nevertheless have some influence. In 1913, in one of his final actions as community leader, he played an important role in stopping a lynch mob from killing two black suspects in the murder of a white man. He pressured the mayor, saying that blacks he had sent throughout the city would burn the town down if the mob was not stopped. The mayor and sheriff stopped the mob.[18]

Smalls died of malaria and diabetes in 1915 at the age of 75.[19] He was buried in his family's plot in the churchyard of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in downtown Beaufort. The monument to Smalls in this churchyard is inscribed with a statement he made to the South Carolina legislature in 1895: "My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life."[32][33

Gov. Ralph Northam Calls Slaves 'Indentured Servants' In Interview, Gets Corrected

Gov. Ralph Northam Calls Slaves ‘Indentured Servants’ In Interview, Gets Corrected

Northam was swiftly corrected by “CBS This Morning” host Gayle King.

By Amy Russo and Hayley Miller

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/ralph-northam-indentured-servants_us_5c61151ae4b0f9e1b17f0417

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam was corrected mid-interview for calling slaves “indentured servants.”

While speaking with “CBS This Morning” host Gayle King, the scandal-plagued Democrat was prompted to discuss his experience in dealing with his own public admission to having worn blackface in 1984.

“We are now at the 400-year anniversary — just 90 miles from here in 1619, the first indentured servants from Africa landed on our shores in Old Point Comfort, what we call now Fort Monroe ― ” Northam began before he was swiftly corrected by King.

“Also known as slavery,” she interrupted.

Northam, nodding in agreement, responded, “Yes.”

<snip>

Indentured servants were men and women who signed a contract that stipulated they would come to America and work for a certain number of years in exchange for passage, room, board and freedom dues. Slaves were brought here ― against their will ― and forced to work without any hope of gaining freedom. Those slaves who chose to flee their “masters” were beaten, starved or killed.

Northam responded to his “indentured servants” remark with a statement saying he was “still learning and committed to getting it right.”

<snip>

“Virginia needs someone that can heal,” he told King. “There’s no better person to do that than a doctor. Virginia also needs someone who is strong, who has empathy, who has courage and who has a moral compass. And that’s why I’m not going anywhere.”

Northam said he’s learned several things since the controversy began unfolding, including that he was “born into white privilege” and that the use of blackface is offensive.

“Yes, I knew it in the past,” he said. “But reality has really set in.”

King pressed him on his apparent revelation about blackface. “You didn’t know the history, know that it was offensive before?” she asked.

?We’re all on a learning curve,” Northam responded. “Certainly, Ms. King, I’m not the same person now at age 59 that I was back in my early 20s.”

He added: “I don’t have any excuses for what I did in my early life.” But I can just tell you that I have learned. I have a lot more to learn. I’m a better person.”

<snip>

Northam’s tenure took a turn at the beginning of February, when an image surfaced from his medical school yearbook showing two men side by side ― one in blackface and the other in a Ku Klux Klan uniform. The governor initially admitted to being one of the individuals pictured, then changed his story, claiming he wasn’t in that particular photo but wore blackface as part of a Michael Jackson costume in a dance competition that same year.

<snip>

It just gets deeper and he's doing all the digging.

Back History: day 11 - We can do it!

Every share makes Black Voice louder!

https://blackmattersus.com/34074-black-history-detroit-housewives-league/

The 3rd Sunday in May is a special day in Black history when we celebrate the founder of the Detroit Housewives League, Fannie Peck.

“It was an attempt by African-American women to essentially try to expand the job market for all African Americans in Detroit by boosting the businesses, Black-owned businesses, and pressuring white-owned businesses to hire African American workers,” Victoria Wolcott, the author of Remaking Respectability: African-American Women in Interwar Detroit said.

Hear @VWidgeon discuss the Detroit Housewives League, 1930s community-based response to unemployment, discriminationhttps://t.co/JaHpKmw5Ye

— Todd Michney (@ToddMichney) May 27, 2017

In the beginning of the twentieth century, African-Americans arrived at Detroit’s Michigan Central Station in huge numbers. It was a part of the Great Migration of Blacks who escaped the South in search of improved economic and political conditions in the urban North. The most significant of these migrants have been the male industrial workers who found jobs in city car production. African-American women have largely been absent from usual stories concerning the Great Migration because they didn’t work at the plants and thus go unnoticed. telling the stories of these women, Victoria Wolcott reveals their vital role in shaping life in interwar Detroit.

“Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work: 1932 Housewives’ League of Detroithttps://t.co/vXQh2Z4eEp@NAACP @Essence

— Jerome Reide (@JeromeReide) March 29, 2017

In 1930s Black women couldn’t afford to stay at home and wait for their husbands. Too many businesses would sell goods and services to Black people but wouldn’t hire them. So in 1930 Detroit women led by Fannie Peck formed a group called the “Detroit Housewives’ League.” It educated women on their buying power and encouraged them to only shop at African-American owned businesses. The group was also initiating big protests and boycotts.

In 1935 they set a huge packing warehouse on fire protesting against high prices, and later joined thousands of Chicago housewives in a march that shut down the city’s entire meat industry.

Black Meatpackers: The Detroit Housewives’ League took on the meat packing industry itself. In 1935, they burned a huge packinghouse. pic.twitter.com/83c8pWaS1M

— The Gist Of Freedom (@Gistoffreedom) December 17, 2016

The initiative became popular and similar groups started to appear all across the country as local chapters a National Housewives’ League of America.

Over the years the Detroit group helped to create over 70,000 jobs for Blacks, both men and women and started to patronize the White businesses that employed African-Americans.

“Real Detroit Housewives League" 9,000+ members: Shut The Meat Industry Down in 1935! | Created 70,000 jobs for Blacks. pic.twitter.com/NisNlr3Yxf

— The Gist Of Freedom (@Gistoffreedom) July 9, 2016

However, the 3rd Sunday in May was a special day in Black history, it was set aside to celebrate the founder of the organization Fannie Peck.

Ivanka Trump: Father 'Had No Involvement' In Security Clearances

Source: Huffpo

Ivanka Trump: Father ‘Had No Involvement’ In Security Clearances For Her, Kushner

Trump said the president had nothing to do with the matter.

By Amy Russo

<snip>

In an ABC News interview released Friday, Trump told the network’s Abby Huntsman there were “absolutely not” any special considerations granted to her.

“There were anonymous leaks about there being issues, but the president had no involvement pertaining to my clearance or my husband’s clearance, zero,” she said.

Trump and Kushner previously held temporary clearances for more than a year and a half while waiting for background checks to wrap up. In May, top clearance was approved for Trump and Kushner’s was restored.

<snip>

Meanwhile the clearances have been the target of criticism from Democrats, including House Oversight Committee Chairman Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) who has launched an investigation into the handling of classified information by President Donald Trump’s transition team and the White House.

Read more: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/ivanka-trump-kushner-security-clearances_us_5c5fe99de4b0f9e1b17dff28

Lies as well a cheetolini.

Profile Information

Name: had to removeGender: Do not display

Hometown: marble falls, tx

Member since: Thu Feb 23, 2012, 04:49 AM

Number of posts: 57,083